|

Mount Weld |

|

|

Western Australia, WA, Australia |

| Main commodities:

P REE Ta

|

|

|

|

|

|

Super Porphyry Cu and Au

|

IOCG Deposits - 70 papers

|

All papers now Open Access.

Available as Full Text for direct download or on request. |

|

|

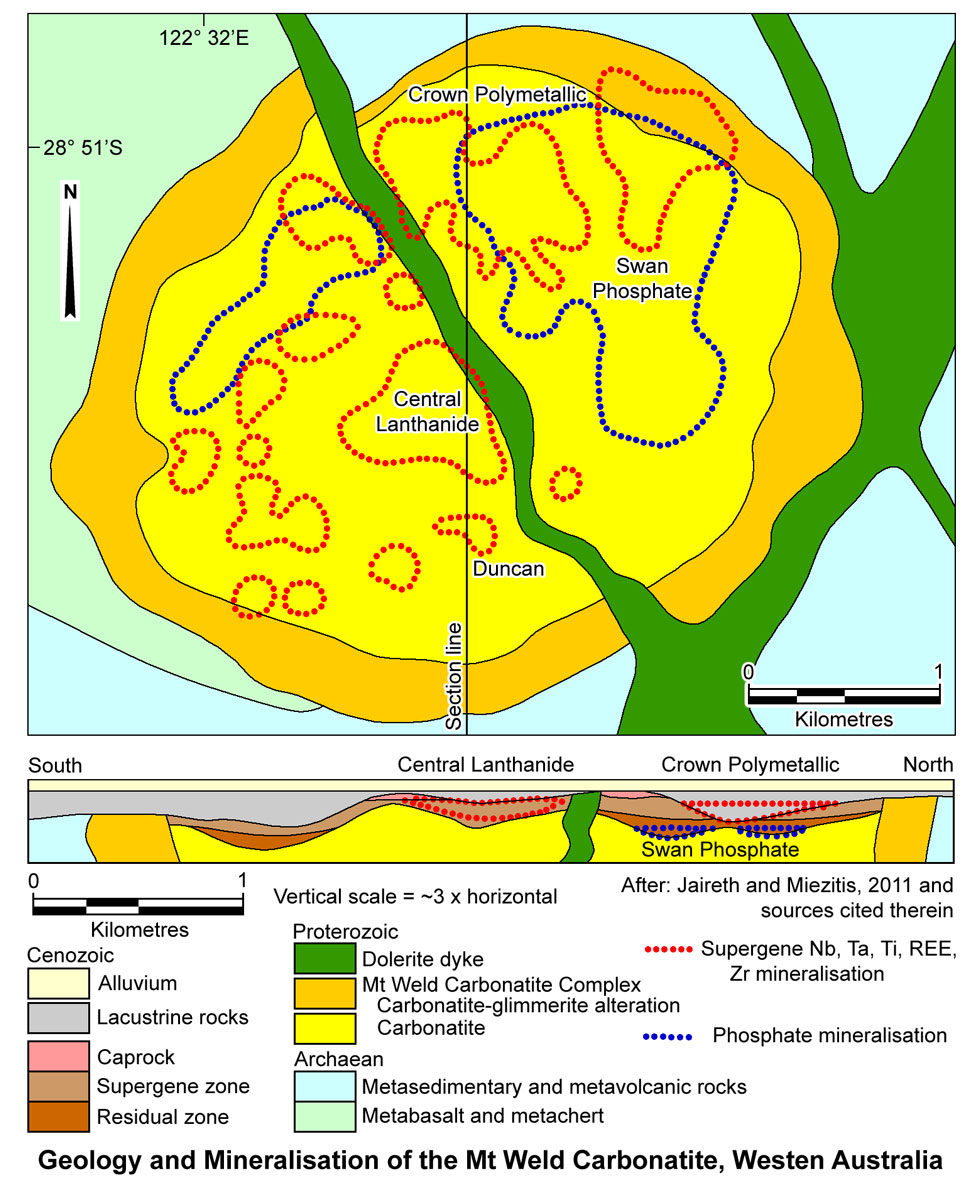

The Mt Weld carbonatite contains substantial deposits of rare earth elements, phosphate, niobium, tantalum and titanium and is located ~32 km SE of Laverton and ~250 km NNE of Kalgoorlie in Western Australia (#Location: 122° 32' 51"S, 28° 51' 45"E).

The Mount Weld carbonatite was discovered after data from a regional Bureau of Mineral Resources aeromagnetic survey in 1966 revealed a pronounced magnetic anomaly in association with a large circular structure concealed below Quaternary alluvium. Modelling of more detailed aeromagnetic and gravity surveys by Utah Development Company and Union Oil Development Corporation indicated a 3 km diameter high density core, surrounded by a 500 m wide lower density annulus. Utah was granted title over the anomaly in 1967, and subsequently confirmed the presence of a carbonatite with diamond drilling. By 1984, Utah had calculated a substantial pre-JORC phosphate resource. However, little work was undertaken on the rare earth mineralisation until a program by Union Oil between 1981 and 1984 outlined a major resource. Over the following 15 years, further exploration was carried out by Wesfarmers-CSBP (who obtained the lease over the phosphate resources), Carr-Boyd Minerals (exploring the REE potential from 1988 to 1991), Ashton Mining Limited (who acquired Carr-Boyd in 1991) in joint venture with Anaconda Nickel Limited. Commencing in 1999, Lynas Corporation began to acquire an interest in the project in a number of tranches, and by April 2002 controlled 100% of Mount Weld Rare Earths Pty Limited, the entity owned by Ashton and Anaconda, that held title to the deposit. Lynas has since proved JORC compliant REE resources and reserves, completed a feasibility study, obtained finance and commenced mining in 2011. The rare earth oxides are mined and initially processed at the Mt Weld Concentration Plant. Concentrates are then shipped to the port of Kuantan in Malaysia, where a complex series of refining and concentration operations produce high quality rare earth minerals. In 2009, Lynas purchased the phosphate mining rights from Wesfarmers, and in 2011, granted a sub-lease to Forge Resources Limited to develop the phosphate resources in the Crown and Swan deposits (Duncan and Willett,1990; Behre Dolbear Australia, 2011; Lynas Corporation, 2015).

The Mount Weld carbonatite intrudes Archaean greenstones in the central part of the fault-bounded, north-south trending Laverton tectonic zone, which lies in the eastern part of the Laverton greenstone belt, part of the greater Norseman-Wiluna greenstone belt within the Archaean Yilgarn Craton of Western Australia.

The Laverton greenstone belt comprises three major cycles of ultramafic to mafic volcanic rocks, separated by thin heterogeneous units of one or more of banded iron formation, chert and carbonaceous shale. The third cycle, which surrounds the Mt Weld carbonatite, is overlain by conglomerate along the western margin of the Laverton tectonic lineament. These greenstones are bounded by a variety of granitoids with intrusive contacts. The greenstone belt has been divided into a series of sectors of open folding and minimal metamorphism, separated by linear to sinuous tectonic zones, characterised by periodic shearing, faulting and peralkaline igneous activity, and subsequent sediment filled grabens. The host sequence and carbonatite have been overprinted by greenschist facies metamorphism (Duncan and Willett,1990).

According to Hoatson et al. (2011) the mid-Palaeoproterozoic Mount Weld Carbonatite belongs to a regional alkaline province represented by coeval low- to high-MgO alkaline ultramafic-mafic igneous rocks, kimberlites, and carbonatites. Isotopic data from oxide minerals, and carbonatite, kimberlite and melonite rock types, yield a precise Re-Os isochron of 2025±10 Ma (Graham et al., 2003; 2004). Incompatible element geochemistry, stable isotope and Sm-Nd isotope data suggest all these rocks are strongly enriched in incompatible elements and are comagmatic. The genetic and spatial relationships between the alkaline ultramafic and carbonatitic melts appear to be controlled by the depth and composition of the sub-continental lithospheric mantle, without significant crustal contamination (Graham et al., 2004).

The Mount Weld carbonatite has been dated at 2021±13 Ma (Rb-Sr from fresh rock; K.D. Collerson, 1982, unpublished data, reported by Hoatson et al., 2011); 2064±40 Ma (K:Ar from a biotite-rich calcite and apatite bearing fragment; A.W. Webb, 1973, unpublished data, reported by Hoatson et al., 2011); 2090±10 Ma (Pb-Pb; Nelson et al., 1988). According to Hoatson et al. (2011), it comprises a steeply plunging cylindrical body of primary carbonatite, ~3 to 4 km in diameter, with an outer 500 m wide annulus of fenitic glimmerite alteration. The glimmerite annulus includes strongly brecciated ferriphlogopite.

According to Hoatson et al. (2011), the altered annulus exhibits a gradational outward transition, from predominantly potassium-rich micaceous rock (glimmerite) to mafic volcanic country rocks of the intruded greenstones. In addition to phlogopite-rich rocks, this zone of alteration also incorporates brecciated wall-rocks, and is characterised by alkali metasomatism under strongly oxidising conditions, typical of fenitisation. However, minor, but widely disseminated sulphides within the carbonatite, suggest the periods of carbonatite invasion occurred under mildly reducing conditions. Duncan (1990) has estimated that since its emplacement, ~4 vertical kilometres of the carbonatite intrusion have been removed by erosion, with a thick residual regolith profile preserved, in contrast to the mineralised Ponton Creek carbonatite ~190 km to the SE, where scouring by Permian glaciation completely removed the palaeo-regolith, without a significant subsequent lateritic profile developed.

However, based on more recent field observations, petrographic studies, and XRD and EDX analyses, Pirajno (2015) suggests the fenitic glimmerite annulus surrounding the Mount Weld carbonatite is probably a maar-type diatreme, formed by processes of phreatomagmatic activity, comprising a carbonatite-glimmerite breccia, agglutinated pyroclastic ash and a vent facies. Pirajno (2015) also suggests the carbonatite-glimmerite breccia material is likely a remnant of hydroclastic to pyroclastic fragmentation due to explosive interaction of a two-phase system containing juvenile fragments and xenoliths of country rocks. These fragments include xenoliths of cumulus apatite, which may represent an early liquidus that crystallised prior to the emplacement of the main carbonatite. The ferriphlogopite (glimmerite) of the fenitic alteration occurs as irregular patches, with associated potassian magnesio-arfvedsonite (detected by EDX analysis), typically with a flow-banded texture and locally replaced by septochlorite sheafs and aenigmatite crystals. There are several generations of veinlets and fracture fillings of sövite, arfvedsonite, ferriphlogopite and local disseminations of pyrite and chalcopyrite. Many of the fragments show plastic-like deformation, possibly resulting from an agglutinated carbonatite pyroclastic (Pirajno, 2015).

The main carbonatite is dominantly calcitic sövite with beforsite, and dolomitic (rauhaugite) igneous rock types that contain more than 50% carbonate, while biotite and apatite may locally predominate (Hoatson et al., 2011; Pirajno, 2015). The average phosphate grade in the primary carbonatite is ~3.5% P2O5. The mineral assemblage within the fresh carbonate locally preserves relict cumulus textures, accompanied by minor intercumulus apatite, biotite, carbonate and magnetite (Hoatson et al., 2011). This assemblage also commonly exhibits distinct granular to globular textures, interpreted as a fluidised vent-facies by Pirajno, 2015). Variable disseminated magnetite, ferriphlogopite, blue magnesio-arfvedsonite, accessory fluoroapatite, pyrochlore, churchite and monazite are recognised in the carbonatite rocks. On the basis of textural relationships, Pirajno (2015) produced a tentative paragenetic sequence as follows: calcite I → pyrochlore → ferriphlogopite → calcite II → calcite + arfevdsonite → pyrite-magnetite.

Carbonatite dykes persist for up to 5 km from the main body.

A thick weathering/regolith layer (10 to >120 m) of laterite overlying the unweathered carbonatite contains high-grade REO deposits and concentrations of niobium, tantalum, zirconium, and other 'rare' metals. The lateritic regolith is divided into a supergene zone, up to 90 m thick, containing the economic rare mineral deposits, overlying a residual zone that is as much as 30 m thick at depths of 50 to 90 m below the surface. This residual layer, below the rare metal enriched supergene zone, contains apatite concentrations of 10 to 36% P2O5, occurring as sub-horizontal sheets of variably cemented apatite-rich sands that are 6 to 30 m thick (Behre Dolbear Australia, 2011).

The leaching of carbonatite by groundwater coupled with mineral alteration (such as alteration of pyrochlore) resulted in the preservation of a residuum rich in primary igneous apatite with high REE contents, and a regolith horizon rich in secondary phosphates and aluminophosphates (Lottermoser and England are, 1988; Willett, Duncan and Rankin, 1989; Lottermoser, 1990).

The regolith is interpreted to have been developed post-Permian, but prior to the overlying Eocene lacustrine sediments, mostly clays, that are from 0 to 50 m thick. The lacustrine deposits and inliers of carbonatite regolith were subsequently buried by an 18 to 24 m thick blanket of transported alluvium, sand and gravel (Behre Dolbear Australia, 2011).

All the currently known economic REE resources at the Mount Weld deposit are hosted within the lateritic regolith above the intrusive carbonatite. Carbonates have been leached from the primary carbonatite and removed by groundwater activity, resulting in the progressive accumulation of primary igneous apatite and minor oxides, sulphides and silicates, accompanied by the replacement, decomposition and oxidation of primary igneous minerals, crystallisation of secondary minerals, and the formation of ferruginous cap rocks. These processes resulted in the formation of a mineralogically and chemically zoned laterite profile, the base of which is defined by a relatively sharp, karst-like interface with the underlying carbonatite. The unweathered carbonatite is overlain by the residual zone containing relict igneous minerals (apatite, magnetite, ilmenite, pyrochlore, monazite, silicates) concentrated by the removal of carbonate. This zone has undergone incipient ferruginisation, with goethite patchily replacing carbonate and variably coating and cementing the detrital grains. Where liberated from the primary carbonate, silicates and sulphides are oxidised (Hoatson et al., 2011; Duncan and Willett; 1990).

The residual layer is overlain by a zone of supergene-enrichment containing abundant insoluble phosphates, aluminophosphates, clays, crandallite group minerals, manganese-bearing and ferric oxides that contain elevated concentrations of REE, Y, U, Th, Nb, Ta, Zr, Ti, V, Cr, Ba and Sr, including economic accumulations of REE, niobium-tantalum and phosphatic minerals. Over most of the carbonatite, the supergene zone was formed as a deep in situ soil, but in some places occurs as a regolithic material transported by sedimentary processes. In these locations, the regolith may be a stratified, poorly sorted, proximal sediment to soil. Extreme lateritic weathering prevailed in the supergene zone over a protracted period of time and resulted in the degradation of the residual magmatic REE-bearing minerals. Pseudomorphous crandallite minerals replaced apatite and pyrochlore, whilst magnetite was oxidised to maghemite, hematite and ultimately to goethite. These secondary iron oxides scavenged Nb, Mn and Ti, whilst Nb, Ta, lathanides, Yt, Ba and Sr were also precipitated in crandallite group minerals (Hoatson et al., 2011; Duncan and Willett; 1990 and Lottermoser, 1990).

The lanthanides were partitioned both laterally and vertically. Very high-grade lanthanide concentrations (up to 45% combined lanthanide oxides) in the regolith are due to secondary monazite which is particularly rich in LREE and low in thorium, and is found as polycrystalline aggregates that often pseudomorph apatite (Lottermoser, 1990). Other REE-bearing minerals recognised include crandallite, rhabdophane, cerianite and churchite. Churchite contains large amounts of high-grade yttrium (up to 2.5% Y2O3) and is an important host to the HREE. The LREE-bearing minerals monazite and rhabdophane are found in the upper part of the residuum, whilst the HREE and Y are preferentially concentrated at depth as xenotime and churchite (Richardson and Birkett, 1995). Yttrium and lanthanides are distributed throughout the carbonatite regolith and are derived from low grade occurrence in the primary carbonatite of the major REE-bearing minerals monazite, apatite and trace synchysite, and to a lesser degree, from other silicate and carbonate minerals (feldspar, calcite, dolomite) that contain trace amounts of REE (Lottermoser and England, 1988; Lottermoser, 1990). The primary apatite within the carbonatite has an average content of ~0.5% lanthanide oxide. REE-bearing phosphatic Lacustrine sedimentary rocks are apparently derived from weathering of fine-grained detrital pyrochlore and apatite that were deposited in the deeper levels of broad palaeodrainage channels (Fetherston, 2004).

The highest niobium-tantalum grades are found in 6 to 15 m thick horizontal units of unconsolidated, highly phosphatic lacustrine sedimentary rocks that grade upwards into smectite clays. Apatite occurs as a residual layer near the base of the regolith, varying from 6 to 30 m thick, at depths of 50 to 90 m below surface. The best beneficiable type is a lightly cemented fine sand of apatite, magnetite and vermiculite. The primary carbonatite contains around 3.5% apatite. Niobium and tantalum bearing pyrochlore, ilmenite and niobium rutile from the primary carbonatite are concentrated in the apatite and magnetite rich residual zone. Grades are generally variable and locally as high as 1.5% Nb2O5 and 0.05% Ta2O5 (Duncan and Willett, 1990). Higher grades of niobium (up to 6% Nb2O5) characteristically form within the supergene zone as crandallite and goethite that have been derived in part from the lacustrine-fluviatile sedimentary rocks.

The most important rare earth resource, the 'Central Lanthanide Deposit' is in the regolith above the central part of the carbonatite, while the higher grade Nb and Ta zones are closer to the outer margins of the pipe. The majority of the REOs are contained within secondary, low Th phosphate minerals with low levels of deleterious elements (e.g., F and Ca). The Central lanthanide deposit contains an indicative mix of predominantly LREE with CeO2 - 46.7%, La2O3 - 25.5%, Nd2O3 - 18.5%, Pr6O11 - 5.32%, Sm2O3 - 2.27% and Eu2O3 - 0.443%, together with minor components of HREE: Dy2O3 - 0.124% and Tb4O7 - 0.068% (Lawrence, 2006).

The lower-grade Duncan REE deposit, SE of Central Lanthanide contains about 25% of the total REO resource, but it has a relatively higher component of the more valuable HREE.

The 'Crown Deposit' in the northern part of the complex has economic resources of niobium, tantalum indicated and inferred resource, while phosphorous mineralisation in the 'Swan Deposit', also in the northern half of the complex has an indicated and inferred resource of phosphorous oxide (MiningNewsPremium.net, 16th March 2011). The 'Anchor Deposit' in the southwest of the Mount Weld complex contains niobium-tantalum mineralisation.

The age of the mineralised laterite is uncertain, although the up to 70 m thick overlying sequence of bioturbated lacustrine clay and sand, is equated to similar sequences in the Eastern Goldfields Province, that are considered to be Late Cretaceous to Early Cenozoic in age (Bunting et al., 1974; Duncan and Willett, 1990). It is suggested the development of the carbonatite weathering profile postdates the Permian glaciation event, which would have removed any pre-existing weathering products. Consequently, the exposure of the carbonatite intrusion and subsequent weathering are interpreted by Hoatson et al. (2011) to have taken place during the Late Mesozoic to Early Cenozoic.

REE enrichment is interpreted to have been the product of long-term leaching and redeposition by groundwater movement (Cassidy et al., 1997). The REE are consider to have undergone pronounced lateral and vertical mobility during weathering, favoured by high fluid:rock ratios, long fluid residence times, abundant REE complexing agents, and the decomposed nature of the primary igneous carbonatite minerals (Lottermoser, 1990). The wide range of pH and alkaline conditions, and the carbonate anion concentrations in the groundwater variably influenced the different stabilities of LREE and HREE complexes which caused fractionation, separation, and deposition of LREE and HREE (Lottermoser, 1990). The development of the strongly REE-enriched central laterite zone was facilitated by lateral groundwater flow towards a central topographic low, whilst the associated decreasing pH of the solutions favoured the mobilisation of large amounts of REE (Hoatson et al., 2011).

The regolith over the carbonatite was estimated (1989) to contain an indicated resource of (Duncan and Willett, 1990):

250 Mt @ 18% P2O5,

270 Mt @ 0.9% Nb2O5,

145 Mt @ 0.034% Ta2O5,

15.2 Mt @ 11.2% lanthanide + yttrium oxides.

Pre-mining resource estimates in 2010 at a cut-off of 2.5% ReO were quoted as (Lynas Corp. web site, 2013):

Central Lanthanide deposit

Measured - 3.55 Mt @ 14.4% REO, 14.3% TLnO, 820 g/t Y2O3

Indicated - 1.44 Mt @ 8.2% REO, 8.1% TLnO, 960 g/t Y2O3

Inferred - 4.884 Mt @ 8.6% REO, 8.5% TLnO, 1120 g/t Y2O3

Total - 9.88 Mt @ 10.7% REO, 10.6% TLnO, 990 g/t Y2O3

Duncan deposit

Measured - 3.65 Mt @ 14.4% REO, 5.2% TLnO, 2700 g/t Y2O3

Indicated - 3.56 Mt @ 8.2% REO, 3.9% TLnO, 2460 g/t Y2O3

Inferred - 0.41 Mt @ 8.6% REO, 4.1% TLnO, 2360 g/t Y2O3

Total - 7.62 Mt @ 10.7% REO, 4.5% TLnO, 2570 g/t Y2O3

Combined total measured + indicted + inferred resource

Total - 17.49 Mt @ 8.1% REO, 7.9% TLnO, 1680 g/t Y2O3

In 2010 the total REE resource amounted to 1.416 Mt ReO.

Crown Deposit niobium, tantalum resources at January 2010 (Lynas Corp.)

indicated + inferred resource - 37.7 Mt @ 1.07% Nb2O5, 1.16% TLnO, 0.09% Y2O3, 0.3% ZrO, 0.024% Ta2O5, 7.99% P2O5;

Swan Deposit phosphate, as at March, 2011 (Lynas Corp.)

indicated + inferred resource - 77 Mt @ 13.5% P2O5.

For detail, consult the reference(s) listed below and "Hoatson D M, Jaireth S and Miezitis Y, 2011 - The major rare-earth-element deposits of Australia: geological setting, exploration, and resources; GeoScience Australia, 204p." and

"Behre Dolbear Australia, 2011 - Independent technical review, Mt Weld rare metals and phosphate resources; A report prepared for Grant Samuel and Associates Pty Limited, and Lynas Corporation Limited by Behre Dolbear Australia, 40p."

According to van Gosen, Verplanck, Seal II and Long 2017, the Resource estimate for REEs at Mt Weld is:

23.9 Mt @ 7.9% TREE for 1.98 Mt of contained TREE.

The most recent source geological information used to prepare this decription was dated: 2014.

Record last updated: 23/8/2016

This description is a summary from published sources, the chief of which are listed below.

© Copyright Porter GeoConsultancy Pty Ltd. Unauthorised copying, reproduction, storage or dissemination prohibited.

|

We are endeavouring to ascertain why those pages that display Google Maps cannot now do so correctly, and will remedy as soon as practical.

|

|

|

|

Duncan R K, Willett G C 1990 - Mount Weld Carbonatite: in Hughes F E (Ed.), 1990 Geology of the Mineral Deposits of Australia & Papua New Guinea The AusIMM, Melbourne Mono 14, v1 pp 591-597

|

Jaireth, S., Hoatson, D. and Miezitis, Y., 2014 - Geological setting and resources of the major rare-earth element deposits in Australia: in Ore Geology Reviews v.62 pp. 72-128.

|

Lottermoser B G, 1990 - Rare earth element mineralisation within the Mt. Weld carbonatite laterite, Western Australia: in Lithos v.24 pp. 151-167

|

Pirajno, F., 2014 - Intracontinental anorogenic alkaline magmatism and carbonatites, associated mineral systems and the mantle plume connection: in Gondwana Research v.27, pp. 1181-1216.

|

Smith, M.P., Moore, K., Kavecsanszki, D., Finch, A.A., Kynicky, J. and Wall, F., 2016 - From mantle to critical zone: A review of large and giant sized deposits of the rare earth elements: in Geoscience Frontiers v.7, pp. 315-334.

|

|

Porter GeoConsultancy Pty Ltd (PorterGeo) provides access to this database at no charge. It is largely based on scientific papers and reports in the public domain, and was current when the sources consulted were published. While PorterGeo endeavour to ensure the information was accurate at the time of compilation and subsequent updating, PorterGeo, its employees and servants: i). do not warrant, or make any representation regarding the use, or results of the use of the information contained herein as to its correctness, accuracy, currency, or otherwise; and ii). expressly disclaim all liability or responsibility to any person using the information or conclusions contained herein.

|

Top | Search Again | PGC Home | Terms & Conditions

|

|