|

Carolina Tin Spodumene Belt - Kings Mountain, Hallman Beam, Core |

|

|

North Carolina, USA |

| Main commodities:

Li Sn

|

|

|

|

|

|

Super Porphyry Cu and Au

|

IOCG Deposits - 70 papers

|

All papers now Open Access.

Available as Full Text for direct download or on request. |

|

|

The Kings Mountain and Hallman-Beam pegmatite hosted lithium deposits are located within the Carolina Tin-Spodumene Belt that straddles the border between North and South Carolina in the Appalachian Mountains of eastern USA. The Kings Mountain Deposit is located in Cleveland County, North Carolina, ~50 km west of Charlotte, North Carolina, and 4 km north of the South Carolina state border. Hallman-Beam is ~17 km NNE of Kings Mountain, proximal to Bessemer City.

(#Location: Kings Mountain - 35° 13' 13"N, 81° 21' 21"W)

The Carolina Lithium Project, which is ~5 km NNE of the historic Hallman Beam mine, is made up of the principal Core Property divided into the North and East pits, and the satellite Huffstetler and Central resources.

The Carolina Tin-Spodumene Belt is ~65 km long by 300 m to 2 km wide, with an open 'S' shape, that from the SE, progresses from NE → near north-south → NNE trending. It is composed of hundreds of granitic pegmatite dykes, many of which contain cassiterite and spodumene, intruded into metamorphic rocks of the Appalachian Orogen. The Kings Mountain and Hallman-Beam pegmatite clusters are situated in the central longitudinal section of the belt. Economic interest in the belt dates from the late nineteenth century, initially focused on cassiterite, in both residual and placer deposits, as well as primary mineralisation in the pegmatites (Ledoux 1889; Pratt and Sterrett 1904; Keith and Sterrett 1917; Kesler 1942). Official and unofficial tin production from the belt is estimated to have been <275 tonnes of metallic tin (Kesler, 1942). The occurrence of beryl in the pegmatites led to interest in outlining a beryllium resource, although ultimately it was lithium that proved to be the major resource, as was discovered in 1906. From the 1950s, when production peaked, to the late 1980s, this belt was the world’s most important lithium source, until cheaper imports from brine deposits rendered the mines of the belt uncompetitive. Lithium mining started at Kings Mountain in 1937, although the main spodumene operations did not commence until the 1950s and 1960s when two major mines were opened. The Kings Mountain Mine, which opened in 1952, was initially operated by the Foote Mineral Company, subsequently to become the Chemetall Foote Corporation. In 2012, that company's lithium operations were demerged as Rockwood Lithium, that was subsequently acquired by Albemarle Lithium. The second of these operations was the Hallman-Beam Mine, which opened in1969, and was operated by Lithium Corporation of America, which was subsequently acquired by FMC Lithium. FMC demerged its lithium operations in 2019 as Livent Corporation, which merged with Allkem of Australia to become Arcadium Lithium in early 2024, and was subsequently acquired by Rio Tinto later in the same year. Although the Kings Mountain mine closed in 1988, the adjacent lithium conversion facility that produces a range of manufacturing materials used in industry, continued operations. Similarly, Arcadium and its predecessors have continued to produce lithium manufacturing materials at Bessemer City in North Carolina, near the old Hallman-Beam Mine. Both of these facilities are significant operations that have continued to manufacture from 'imported' concentrates since the associated mines were shut down, although Albemarle is engaged in expanding resources and is seeking approval to resume open pit mining at Kings Mountain. Potentially economic resources are also being investigated at the Carolina Lithium Project, north of the Hallman-Beam mine.

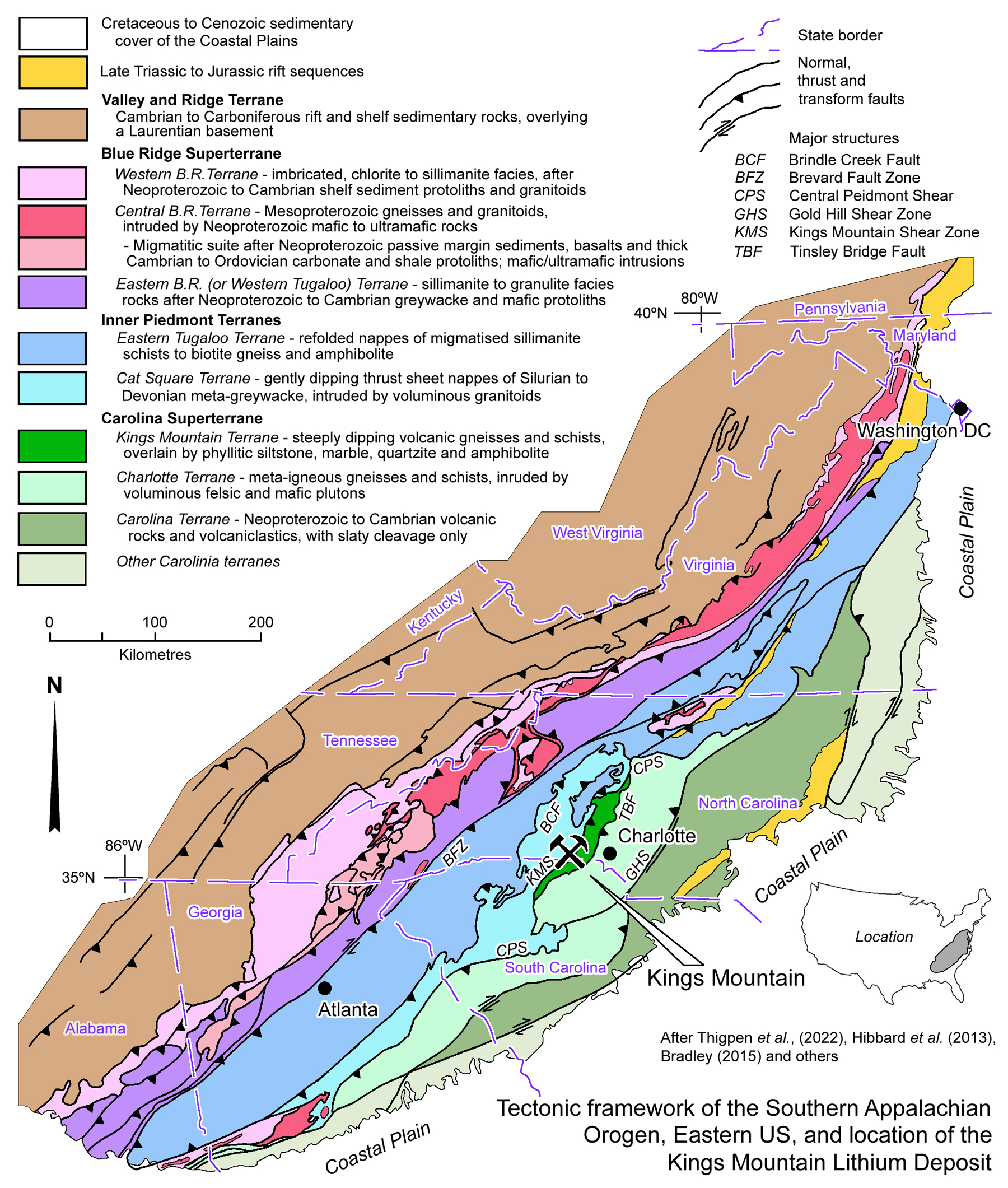

Tectonic Setting

The Carolina Tin-Spodumene Belt lies within the Appalachian Orogen of eastern USA. This orogen is part of an extensive, previously composite, but evolving belt of Palaeozoic orogenesis that extends from the Caledonian and Variscan in Europe, via the Appalachian Orogen to the Ouachita-Alleghanian Orogen in southeastern US and Mexico. It formed along the eastern margin of Laurentia, following the Late Neoproterozoic breakup of the supercontinent Rodinia, and evolved over the succeeding period that ended with the Late Palaeozoic coalescence of most continents to form the supercontinent Pangea. Subsequently, the opening of the North Atlantic Ocean separated the North American continent from Africa and Europe.

The development of the Appalachian Orogen, and the broader belt of orogenesis in Europe and North America, was governed by the interaction of three continental blocks, Gondwana, Baltica and Laurentia, and the Iapetus and Rheic oceans. The Iapetus Ocean opened in the Late Ediacaran epoch of the Neoproterozoic and the Early Cambrian, thus breaking up Rodinia into Gondwana on one side, and Laurentia and Baltica on the other, although the latter two were also separated by another zone of rifting. This major extensional event gave rise to an extensive Early Palaeozoic passive margin on the North American section of Laurentia facing the Iapetus Ocean. At the same time, during the Late Cambrian to Early Ordovician on the opposite of the same ocean, a succession of peri-Gondwanan micro-continental slivers/terranes, from Ganderia, Avalonia and Meguma in Canada, Carolinia in the US, to Yucatan, Oaxaquia and Chortis from Mexico to Honduras, were progressively spawned from Gondwana. These began to migrate NW towards Laurentia. In the process, the Iapetus Ocean was consumed by subduction ahead of these microcontinents, whilst the Rheic Ocean opened in their wake. During their passage, the eastern most of these microcontinents first amalgamated with Baltica to their NE. The micro-continental terranes subsequently successively collided with Laurentia in the SW to form the Appalachian and Ouachita-Alleghanian orogens, while to the NE, Baltica also collided with Laurentia in North America and Greenland to form the Caledonian Orogen. These collisions, which had been completed by the Late Silurian, amalgamated Laurentia and Baltica to form Laurussia. Subsequently the Rheic Ocean began to close and Gondwana collided with the trailing edges of the microcontinents previously accreted to Laurussia marking a southeastern migration of the Appalachian and Ouachita-Alleghanian orogens. However, in Europe, Gondwana collided with what was Baltica, substantially separating it from the Caledonides, to form the Variscan Orogen of central Europe. This collisional zone was further complicated by microcontinets such as Eastern Avalonia, Iberia and Cadomia that had separated from Gondwana and collided with the southern margin of Baltica prior to the arrival of Gondwana, separating the Variscides from the Mauritanides of northwestern Africa (Nance et al., 2012).

The Southern Appalachian Orogen in the US preserves a complex history involving at least five discrete orogenic pulses, including the pre-Appalachian 1.25 to 0.90 Ga Mesoproterozoic Grenville basement; and those of the Appalachian Orogeny, namely: i). the 480 to 440 Ma Taconic D1; ii). 423 to 380 Ma Acadian D2; iii). 366 to 350 Ma Neoacadian D3; and iv). 330 to 280 Ma Alleghanian D4 events. These reflect the interaction between the original Laurentian continent to the NW, and the progressive collision of i). Gondwanan microcontinents; ii). rocks deposited within the Iapetus Ocean between and over the microcontinents, iii). associated magmatic arcs, both intra-oceanic and on the active margins of the microcontinents, and iv). preserved slices of oceanic rocks. Telescoping along major orogen-parallel thrusts accounted for hundreds kilometres of shortening and imbrication, particularly during the culminating Alleghanian Orogeny, which marks the continental collision between Laurentia and Gondwana, forming the supercontinent Pangea.

NOTE: The description of the Southern Appalachian Orogen below is possibly in more detail than needed to explain the setting of the Carolina Tin-Spodumene Belt, but will be used as a setting reference for other deposits of the Orogen. It will also just concentrate on the southern section of the greater Appalachian Orogen.

Within this framework, the Southern Appalachian Orogen is composed of a series of linear terranes that are, from NW to SE:

• The Valley and Ridge Terrane to the NW, that is characterised by a series of elongate parallel ridges and valleys that are underlain by alternating soft and resistent Palaeozoic sedimentary rocks that are repeated by folding and faulting. It represents a foreland thrust belt, related to the Alleghanian collision of Gondwana with Laurentia. The oldest exposed units were deposited at ~520 Ma in the Cambrian, overlying Laurentian basement. The sequence comprises:

i). Cambrian to Ordovician carbonates deposited in the Iapetus Ocean on the divergent continental margin;

ii). Middle to Upper Ordovician immature clastics derived from uplifted sources associated with the Taconic Orogeny;

iii). Silurian to Lower Devonian quartz arenites and carbonates deposited during a local inter-orogenic interval of tectonic quiescence, and

iv). Upper Devonian to Lower Carboniferous clastic rocks laid down during the Acadian/Neoacadian Orogeny.

• The Blue Ridge Superterrane (or Tectonic Province) in the NW section of the southern Appalachian Orogen, and immediately to the SE of the Valley and Ridge Terrane, separated by a series of NW vergent thrusts; including the Great Smoky and Holston Mountain faults. It is divided into three terranes. These are:

i). the Central Blue Ridge Terrane, which has a linear core of 1.2 to 1.0 Ga Mesoproterozoic middle- to lower-crustal Grenville age ortho- and para-gneisses and granitoids, including orthopyroxene-bearing charnockites, all of which are intruded by 480 to 460 Ma mafic to ultramafic complexes. This older core occurs as a string of thrust bound basement massifs. These are succeeded by the 730 to 700 Ma, felsic Robertson River plutonic and volcanic complex, which is, in turn, overlain by younger Neoproterozoic metasedimentary passive margin sequences. The metasedimentary sequences include the thin clastics of the Swift Run Formation, followed by the 30 to 120 m thick, ~570 Ma Neoproterozoic Catoctin Formation metabasalts that cover an area of >4000 km2 and reflect the opening of the Iapetus Ocean. The overlying Cambrian sequence is represented by the shallow marine Chilhowee Group, comprising the ~380 m thick Weverton Formation quartz meta-sandstone, meta-conglomerate, laminated meta-siltstone and quartzose phyllite; followed by the 600 to 840 m thick Harpers Formation phyllite and thinly bedded meta-sandstone; and the Antietam Formation quartz arenite. The Chilhowee Group is, in turn, overlain by an up to >3000 m thick package of Cambrian to Ordovician carbonate and shale (Fichter, Whitmeyer, Bailey and Burton, 2010). This older Laurentian core and cover sequence is structurally overlain to the NW by

ii). the Western Blue Ridge Terrane, composed of a stack of imbricate thrust sheets and duplexes of the Neoproterozoic to Cambrian rift to passive margin sequence conglomerates and slates, and variable sandstones, as described for the cover sequence above in the Central Blue Ridge Terrane. These increase in metamorphic grade from chlorite to sillimanite facies from NW to SE (Thigpen et al., 2022). To the SE of the Central Blue Ridge Terrane,

iii). the Eastern Blue Ridge Terrane, or Western Tugaloo Terrane comprises Neoproterozoic to Cambrian greywacke-schist, amphibolite, pelitic garnet-aluminous schist and quartzite-schist members that progressively increase in metamorphic grade to the SE from kyanite and sillimanite to upper amphibolite and granulite facies (Thigpen et al., 2022).

Thigpen et al. (2022) have undertaken a program of dating metamorphic monazite within Neoproterozoic cover protoliths of the Western, Eastern and Central Blue Ridge Superterrane, supported by thermodynamic modelling of metamorphic minerals. This has shown that the relatively intact Barrovian metamorphic progression within these three terranes is solely from an Ordovician Taconic (480 to 440 Ma) thermal-metamorphic event, the core of which yields peak conditions of 775°C and ∼11.5 kbar (~30 km depth). This study is taken to suggests the Blue Ridge Superterrane comprises Mesoproterozoic (Grenville) Laurentian basement and 760 to 610 Ma Neoproterozoic metasedimentary passive margin cover, over which a thick, imbricated accretionary wedge was developed, separated by a NW vergent thrust (Massey and Moecher, 2005; Thigpen et al., 2022). The accretionary wedge is composed of deep water turbidites, basement slivers, oceanic fragments and island arc volcanic sequences. It is interpreted to be supra-subductional, ahead of and above the east dipping intraoceanic subduction of the Iapetus Ocean. Whilst no undisputed preserved supra-subduction magmatic arc has been identified in the southern Appalachians, the presence of 480 to 460 Ma arc- and MORB-related mafic and ultramafic rocks in the central and eastern Blue Ridge terranes, trace-element geochemistry and the preservation of Taconic eclogite-facies metamorphism, have together been taken to indicate that both arc volcanism/plutonism and subduction of oceanic crust were active below the superterrane during the Taconic orogenesis. High Pressure and High Temperature metamorphism is envisaged to have resulted from subduction of Laurentian continental crust basement and cover, and adjacent accretionary wedge rocks, which followed the Iapetus Oceanic slab into the subduction zone. Exhumation during subsequent slab-detachment and tectonic rebound, as well as uplift caused by later orogenesis, exposed the metamorphic core of the terrane.

The rocks of the accretionary wedge within the eastern Blue Ridge Terrane constitute the Western Tugaloo Terrane.

• The Inner Piedmont Terranes, which are to the SE of the Blue Ridge Superterrane, separated by the major NW-vergent, dextral, Brevard Fault Zone, a thrust that extends from North Carolina to Alabama. These terranes form the 360 to 345 Ma Neoacadian migmatitic core of the southern crystalline Appalachians (Griffin, 1971; Merschat et al., 2012). The bulk of the Inner Piedmont Terranes are composed of refolded nappes of peri-Laurentian migmatised biotite gneisses, sillimanite-quartz-muscovite schists, amphibolites and orthogneisses, that make up the Eastern Tugaloo Terrane, derived from similar accretionary wedge protoliths as those of the Eastern Blue Ridge Terrane, i.e., the Western Tugaloo Terrane. As such, the combined Western and Eastern Tugaloo terranes, straddle the boundary between the Blue Ridge Superterrane and the Inner Piedmont Terranes (Allard and Whitney, 1994). The metamorphism of the Inner Piedmont Terranes would appear to have occurred during the Late Devonian Neoacadian collision and imbrication with the Carolina Superterrane, as described below.

The southeastern section of the Inner Piedmont Terranes block comprises the structurally overlying, mixed Laurentian and peri-Gondwanan affinity Cat Square Terrane, exposed as several gently-dipping thrust sheets/nappes. These are composed of Late Silurian to Early Devonian pelitic schist and meta-greywacke, after clastic sedimentary protoliths, with rare ultramafic and mafic rocks. They are intruded by several voluminous Devonian to Early Carboniferous (Mississippian) peraluminous granitoids and charnockites, and are juxtaposed over the East Tugaloo Terrane by the Brindle Creek fault (Merschat et al., 2012).

The western flank of the Inner Piedmont Terranes block is dominated by Taconian Ordovician to Silurian plutons, although some related to the Alleghanian orogeny also occur in the same area, and may be less deformed. The density of granitoid intrusions increases to the SE, reaching around 12% of the northern Cat Square Terrane (Merschat et al., 2012). The largest of these plutons is the 2544 km2, 355 ±2 Ma, Upper Devonian Cherryville Granite, a medium- to coarse-grained, weakly foliated, two-mica granite, located within and near the eastern margin of the Cat Square Terrane, elongated NNE-SSW, immediately to the west of, and parallel to the Kings Mountain Terrane. No Mesoproterozoic basement has been mapped in the eastern Inner Piedmont Cat Square Terrane, and no plutons older than 407 Ma are known in this segment. Peak metamorphism within the Inner Piedmont Terrane occurred during the Neoacadian D2 phase, straddling the Devonian to Carboniferous transition. In the Kings Mountain area, the Inner Piedmont Terranes are bound to the SE by the Kings Mountain Shear Zone which marks a dramatic change in structural style. The steeply dipping layering and foliation of the Kings Mountain Terrane to the SE contrasts with the more shallow inclinations of the Inner Piedmont Terranes (Horton 2008).

The Kings Mountain Shear Zone is a moderately SE dipping zone of ductile and semi-brittle deformation. It has beeen interpreted to be a section of the laterally more extensive Central Piedmont Shear Zone that juxtaposes the Inner Piedmont Terrane with both the Kings Mountain Terrane and other members of the Carolina Superterrane to the NE and SW (Dennis, Shervais and LaPoint (2012). It is observed to truncate stratigraphy on both sides. The same authors (and others cited therein) interpret this composite shear zones to represent a Middle Carboniferous (Upper Mississippian to Pennsylvanian) oblique dextral shear zone, with a significant NW vergent thrust component. Displacement on this structure placed Neoproterozoic to Cambrian rocks of the Carolina Superterrane (most of which were metamorphosed at the Neoproterozoic-Cambrian transition) over the protoliths of the Wenlock-Ludlow Mid to Upper Silurian Cat Square Terrane paragneisses that did not experience peak metamorphic conditions until the Upper Devonian.

The Cat Square Terrane would appear to represent deposition within the Iapetus Ocean east of Laurentia, but also receiving detritus from the peri-Gondwana Carolina Superterrane that was approaching from the east. It may represent an accretionary prism in front of the Carolina Superterrane. It was then thrust west over the Inner Piedmont Terrane as the Carolina Superterrane approached across the closing Iapetus Ocean and collided with the Laurentian margin. The resultant imbrication was compounded by the approach of the following main mass of Gondwana as the Rheic Ocean was subducted and Gondwana collided with the trailing edge of the Carolina Superterrane.

• The Kings Mountain Terrane - is generally regarded to be part of the Carolina Superterrane. The ~100 x <3 to 30 km, NE-SW elongated terrane (Dennis et al., 2020) has been divided into two formations (after Horton, 2008 and Dennis, Shervais and LaPoint, 2012):

i). the Battleground Formation, composed of a lower suite of felsic meta-volcanic rocks and interlayered schist. The meta-volcanic facies include hornblende gneiss, felsic schist and gneiss, plagioclase-crystal meta-tuff, siliceous meta-tuff, volcanic meta-conglomerate, and mottled phyllitic meta-tuff. These facies grade laterally and vertically into a siliceous biotite-muscovite schist that lacks volcanic textures, and is interpreted to represent an epiclastic or sedimentary protolith that is, in part, hydrothermally altered volcanic material related to base metal and barite mineralisation found within the sequence. The upper section of this formation is composed of interlayered meta-sedimentary and lesser meta-volcanic rock; which include quartz-sericite phyllite and schist, as well as distinctive quartz-pebble meta-conglomerate horizons, manganiferous formation, and aluminous and micaceous quartzite. One of the lower meta-conglomerate units yields detrital zircons of latest Middle Cambrian age. These rocks, and those of the overlying Blacksburg Formation, are among the youngest stratified rocks in the Carolina Superterrane. The sequence is capped by an undivided meta-dacite and meta-trondhjemite unit.

ii). the overlying Blacksburg Formation, is mainly composed of phyllitic, frequently graphitic metasiltstone and interlayered marble, laminated micaceous quartzite, and hornblende gneiss and amphibolite with a basaltic composition. Minor calc-silicate interlayers are also present. The Blacksburg and Battleground formations are predominantly separated by the dextral Carboniferous Kings Creek Shear Zone, although locally there appears to be a conformably stratigraphic relationship between the two (LaPoint, 1992).

The Kings Mountain Terrane is separated from the Charlotte Terrane to the SE by the Tinsley Bridge Fault, which is cut by the 306 ±2 Ma, (Late Carboniferous) Pacolet Granite (Mapes, 2002).

The Kings Mountain Terrane would appear to represent deposition on the Iapetus Ocean floor ahead of the advancing Carolina Superterrane. It was subsequently strongly folded and sandwiched between the latter and the Cat Square Terrane of the Inner Piedmont Terranes block as the two collided, then again after the Gondwana collision with the Carolina Superterrane.

• The Carolina Superterrane extends over a NE-SW interval of ~600 km, from central Georgia to central Virginia, and a width of up to 120 km. It is located to the SE of the Inner Piedmont Terrane, and is composed of a suite of terranes, the western-most of which is the Kings Mountain Terrane, as described above. The latter is bounded to the SE by the more extensive, NE-SW elongated Charlotte Terrane, which is, in turn, structurally juxtaposed against the parallel Carolina Terrane further to the SE. A number of much smaller terranes are found to the SE and east of these, but will not be discussed herein.

The Charlotte Terrane, is juxtaposed against the Kings Mountain Terrane on its NW margin, and beyond the structurally terminated northeastern and southwestern extremities of the latter, it abuts the Inner Piedmont Terrane. The Charlotte and Kings Mountain terranes are separated by the Tinsley Bridge Fault. Where the latter fault merges with the Central Piedmont Shear Zone to both the NE and SW, truncating the Kings Mountain Terrane at both ends, the latter shear zone separates the Charlotte and Inner Piedmont terranes. The Charlotte Terrane is dominated by plutonic rocks that range in age from Neoproterozoic to late Palaeozoic. It is characterised by numerous plutons with granitic to gabbroic composition that intrude a suite of mainly meta-igneous gneiss and schist, meta-volcanic rocks, metamorphosed mafic complexes (basalt and gabbro) and ultramafic rocks, with minor phyllite, mica schist and quartzite. Marble is found at the western edge of the terrane. These intrusives are divided into three main suites,

i). the Cambrian 545 to 490 Ma Old Plutonic Superunit composed of meta-quartz diorite, meta-granodiorite and meta-gabbro, but is dominated by mafic metavolcanic and meta-plutonic rocks that intrude their own volcanic piles, and were dominantly metamorphosed to amphibolite-facies before 535 Ma;

ii). the Late Silurian to Late Devonian 426 to 350 Ma Concord-Salisbury gabbro and granodiorite, which occur as sheet-like intrusions of differentiated gabbro, local volcanic centres, ring complexes up to 13 km in diameter, and smaller bodies of diorite, monzonite and syenite; as well as small granodiorites; and

iii). the Carboniferous 350 to 280 Ma Landis Superunit, largely composed of the Landis Granite, a very coarse-grained, porphyritic, potassium-rich 'big feldspar' granite (Wilson and Jones, 1986; Wilson, 1981).

The bimodal nature of both the gabbro-granodiorite plutons and volcanism, has been taken to suggest an extensional tectonic environment, most likely reflecting the rifting from Gondwana associated with the opening of and continued expansion of the Rheic ocean (Wilson and Jones, 1986). However, the younger Landis granites may instead be related to the closure of the Iapetus Ocean (Wilson and Jones, 1986).

The Charlotte and Carolina terranes differ, in that the former contains volumetrically much more magmatic rocks in the older superunit, and incorporates large mafic–ultramafic complexes not common to the suprastructural Carolina Terrane (Hibbard et al., 2002). In addition, the terrane boundary between the two marks a change from high- to low-grade metamorphism between the Charlotte and Carolina terranes respectively (e.g., Hibbard, et al., 2002).

The structure of the terrane is characterised by a steep schistosity that is axial planar to tight, upright folds with axial traces parallel to the strike of the terrane (Butler and Secor, 1991).

To the SE, the Charlotte terrane is bounded by the dextral strike-slip Beaver Creek Shear Zone, along which displacement ceased before intrusion of the ~415 Ma Lower Devonian Newberry granite. A belt of retrograde facies eclogitic rocks that predate the granite are found within the terrane, immediately adjacent to its contact with the Carolina Terrane in South Carolina.

The Carolina Terrane constitutes the heart of the Carolina Superterrane, and is one of the largest accreted peri-Gondwanan crustal tracts within the Appalachian Orogen, extending over an interval of >750 km, from Georgia in the SW, to Virginia in the NE. It is also known as the Carolina Slate Belt, as metamorphism has not progressed beyond the development of slaty cleavage, which is characteristic of the terrane, in contrast to the schists and gneisses of the Charlotte Terrane. The terrane comprises three main lithotectonic elements, the older, Cryogenian, fault-bounded Roanoke Rapids Complex, the Ediacaran Hyco Formation magmatism, and the younger Neoproterozoic to Early Cambrian Albemarle Group. The last two magmatic suites are separated by an unconformity, and the locally preserved Virgilina Sequence, which is composed of clastic sedimentary rocks with subordinate volcanics (Pollock, Hibbard and Sylvester, 2010).

Only vestiges of the ~670 Ma Roanoke Rapids Complex and surrounding country rock sequence are preserved. These comprise an assemblage of

low-metamorphic grade, mafic to ultramafic rocks, the Halifax County Complex, which are surrounded by plutonic, felsic volcanic, meta-volcanic and phyllitic volcaniclastic rocks, and 672 Ma granite. Geochemistry and geological data suggest these complexes were built, at least in part, on a substrate of older, isotopically evolved, continental crust (Pollock, Hibbard and van Staal, 2012).

The >4900 m thick, 633 to 612 Ma Hyco Formation is predominantly composed of felsic to intermediate magmatic rocks, largely sub-aqueous pyroclastics, characterised as tholeiitic to calc-alkaline compositions. Geochemical and other data are said to strongly suggest the Hyco Formation is composed of juvenile, largely mantle-derived crust, and represents a mature 'arc' or 'pile' built upon an oceanic substrate. After a hiatus of ~24 m.y., this arc was overlain by the dominantly metasedimentary Virgilina Sequence, deposited between 630 and 610 Ma. This sequence is composed of weakly metamorphosed epiclastic sedimentary rocks, conglomerate, argillite, tuffaceous mudstone, mafic tuff, mafic lapilli tuff, and possible mafic lavas, with local felsic volcanics. Deposition was followed by another ~10 m.y. hiatus (Pollock, Hibbard and Sylvester, 2010).

The 555 to <528 Ma Albemarle Group extends from central North Carolina, southward into Georgia. It is ~12 700 m thick and is characterised by a thick felsic volcanic base, conformably overlain by Neoproterozoic to Early Cambrian clastic sedimentary rocks with interspersed lenses, dykes and stocks of felsic to mafic magmatic rocks (Hibbard et al., 2013 and references cited therein).

Two major tectonothermal events have overprinted rocks of the Carolina Terrane. The first at ~578 to 545 Ma in the latest Neoproterozoic Ediacaran, affecting both the Hyco Formation and the Virgilina Sequence. The second straddled the Late Ordovician and likely continued into the Early Silurian (Pollock, Hibbard and Sylvester, 2010).

Evolution of the composite Appalachian Orogen - A possible interpretation of the development of the orogen might entail:

- Opening of the Iapetus Ocean and separation of Gondwana and Laurentia, as reflected by the ~670 and 612 Ma Roanoke, and Halifax complexes and Hyco Formation bimodal sequences on the trailing edge of the retreating Gondwana continent. Magmatism during this interval was accompanied and followed by deposition of the Virgilina Sequence.

On the Laurentian side of the ocean, the precursor 730 to 700 Ma, felsic Robertson River plutonic and volcanic complex of the Blue Ridge Superterrane, and the ~570 Ma Neoproterozoic Catoctin Formation metabasalts within the passive margin sequence are also a reflection of this rifting and opening of the Iapetus Ocean. Note that significant translation occurred between the Gondwana and Laurentian blocks between their rifting and subsequent reunification, and hence events and stratigraphic units will not closely correlate between the two where subsequently juxtaposed.

- Initial closure of the Iapetus Ocean - following the opening, subsequent closure was affected by east vergent intra-oceanic subduction proximal to the Laurentian margin, within what became the Blue Ridge Superterrane, as described in the 'Blue Ridge Superterrane' paragraph previously. This eventually ceased, as buoyant, thicker, Laurentian continental crust followed the oceanic slab into the subduction zone, thus 'plugging' it. To compensate, and accommodate continued contraction, a new, east dipping intra-oceanic subduction zone was developed to the east, proximal to the Gondwanan margin of the Iapetus Ocean.

- Initiation of the intra-oceanic Charlotte Arc, proximal to the western margin of Gondwana, above this newly formed, eastward dipping subduction zone consuming the Iapetus Ocean. This was marked by the late Ediacaran to Early Cambrian 545 to 490 Ma Old Plutonic Superunit of the Charlotte Terrane, and the 555 to 528 Ma Albemarle Group to the east on the margin of Gondwana that subsequently separated to form the Carolina Terrane.

- Seperation of the Carolina Terrane from Gondwana in the Early to Middle Cambrian, at ~500 Ma. This formed a micro-continental sliver pursuing the Charlotte Arc/Terrane westward across the Iapetus Ocean. It was brought about by the opening of the Rheic Ocean to the east, in its wake, and by west-dipping subduction below the Charlotte Arc/Terrane of the oceanic crust separating the two newly formed terranes to the west. During this stage, the Iapetus Ocean continued subducting below the Charlotte Arc.

- Collision between the Charlotte and Carolina terranes - the section of oceanic crust separating the Carolina Terrane and the Charlotte Arc/Terrane and subducting below the latter was consumed, until the two collided. Eclogite metamorphism in the Charlotte terrane of South Carolina may be related to this event.

- Formation of the Cat Square Terrane, deposited during the Late Silurian to Devonian in the Iapetus Ocean between Laurentia and the approaching Carolina Superterrane, most likely as an accretionary prism on the leading edge of the latter.

- Formation of the Kings Mountain Terrane in the Iapetus Ocean, on the margin of the advancing Charlotte Terrane above and behind the accretionary prism, such that, on collision between the Carolina Superterrane and Laurentia, it was sandwiched between the former and over the Cat Square Terrane.

- Collision between the Carolina Superterrane and Laurentia, during the Acadian at ~400 Ma, which may be reflected by a metamorphic event from 358 to 391 Ma in the Devonian (e.g., Hatcher 2005).

- Collision between the main Gondwana continent and the trailing edge of the Carolina Superterranes. This continent-continent collision event, marked the Alleghanian Orogenesis, which sandwiched a number of smaller Gondwanan microcontinents. It led to the imbrication to progressively greater depths from the Caroline → Charlotte → Kings Mountain → Cat Square → Eastern Tugaloo terranes → the Eastern Blue Ridge Superterrane. This progression also corresponds to an increase in metamorphic grade, peaking in the Inner Piedmont Terranes. During this imbricate stacking event, the southern Appalachian crust and lithosphere reached its greatest thickness, before undergoing extension that progressed from orogenic collapse and exhumation in the core of the orogen, to continental rifting, and eventually to the opening of the Atlantic Ocean (Dewey, 1988).

In areas where the remaining crust is still >30 km thick (Wagner et al., 2012), rocks are exposed that were intruded and metamorphosed at depths of ~20 km during the Alleghanian (Stowell et al., 2019). This and other data suggest that at the height of the Alleghanian Orogeny, the imbricated crust was of the order of 55 to 70 km thick. In the core of the orogen, in the Inner Piedmont Terranes, these mid- to lower-crustal rocks were metamorphosed to upper amphibolite to granulite facies with widespread partial melting producing anatectic granitoids, migmatites and pegmatites. Foster et al., 2023 note that widespread syn- to post-orogenic Alleghanian plutons return U-Pb zircon ages that span a range from ~340 to 290 Ma for magmas intruded at similar mid-crustal levels. The age range antectic crystals in each of these intrusion typically span of ~10 m.y. (Lin, 2015). These are taken tio indicate the (near) continuous presence of partial melt in the orogenic system over a protracted period. Monazite U-Pb and Sm-Nd ages of garnet from the metamorphic rocks show a similar protracted interval of high temperatures in the middle crust during the Alleghanian (Mueller et al., 2011; Stowell et al., 2019). These data are taken to show that Alleghanian metamorphism in the Southern Appalachian Orogen occurred progressively and continuously for ~30 to 50 m.y. as thermal, barometric and fluid conditions evolved within the orogenic pile between ~345 to 295 Ma (Foster et al., 2023).

- Tectonic exhumation and Post-orogenic extension. The core of the orogen remained under contraction and imbrication to between 260 and 240 Ma in the Permian to Triassic, accompanied by high-temperature and low-pressure metamorphism, and partial melting, at mid-crustal levels. Never-the-less, extensional collapse at depth had begun as early as 300 to 280 Ma in the Late Carboniferous. The vertical collapse was compensated by i). horizontal extension at depth above shallow dipping listric decollements exposed at surface in the Valley and Ridge Terrane to the NW as shallow, SE dipping thrusts, and ii). lateral horizontal flow of partially melted rocks in the ductile middle-crust (Foster et al., 2023).

According to Foster et al. (2023), thermochronologic and structural data suggest that the Alleghanian hinterland was progressively

exhumed from the Brevard Fault in the NW, towards the southeastern margin of the Carolina Superterrane, resembling exhumation of the lower plate of a regional metamorphic core complex beneath an extensional detachment. The un-metamorphosed rocks of the terrane to the SE of the Carolina Superterrane (the Suwannee Sequence and Precambrian basement rocks) represent the upper plate to the detachment system (e.g., Heatherington and Mueller, 1997; Steltenpohl et al., 2008; Ma et al., 2019).

Following the amalgamation of Pangea at the height of the Alleghanian Orogenesis, the supercontinent began to breakup, facilitated by extensional detachments to diachronously open nascent ocean basins along what was to become the Atlantic margins from the Triassic to Cretaceous (e.g., Lister et al., 1991). This culminated in the opening of the North Atlantic Ocean.

Carolina Tin-Spodumene Belt

The Carolina Tin-Spodumene Belt is composed of hundreds of en echelon pegmatite dykes and sills intruded into an amphibolite-facies mica schist and amphibolite suite, distributed over a 300 m to 2 km width and ~65 km length, within and immediately west of the Kings Mountain Shear Zone. This shear zone forms the southeastern flank of the Cat Square Terrane, the easternmost of the Inner Piedmont Terranes, separating it from the distinctly different Kings Mountain Terrane. The Inner Piedmont Terranes represent the most intensely metamorphosed corridor within the southern Appalachian Orogen, although the metamorphic grade in the immediate proximity of the spodumene-bearing pegmatites is somewhat lower, in the staurolite zone, in contrast to the Cat Square Terrane rocks to the west of the belt (Swanson, 2012).

Rocks of the Inner Piedmont and Kings Mountain terranes have been subject to multiple periods of deformation, although intrusion of the spodumene pegmatites preceded the last of these events (Horton 1981, Spanjers 1990). In particular, the spodumene pegmatite were emplaced during the waning stage of deformation in the Kings Mountain Shear Zone (Horton, 1981). The pegmatites range from non-foliated to strongly foliated, and locally crosscut foliation in the Kings Mountain Shear Zone. Locally, particularly near wall-rock contacts, blastomylonitic or augen-gneiss textures are developed.

Spodumene pegmatites are most abundant in and near, and hence are predominantly intruded into, bodies of amphibolites of the Cat Square Terrane, with the remainder within mica schists. A small number are hosted by mica schist to phyllites of the Blacksburgh Formation of the Kings Mountain Terrane, where it is falls within the Kings Mountain Shear Zone. Most of these pegmatite dykes are ≤3 m thick. The largest, thickest and longest were emplaced in joints, and range in size from 8 x 150 m to 130 x 1000 m in plan.

The Spodumene Pegmatite dykes have been dated at 340 ±10 Ma (Rb-Sr; Kish and Fullagar, 1996) and 352 10 Ma, (Kish, 1977). They are generally white, medium-to coarse-grained, and generally unzoned. The average composition is estimated as: 32% quartz, 27% albite, 20% spodumene, 14% K feldspar/microcline, 6% muscovite, and 1% others (Kesler 1961). Trace amounts of beryl, manganapatite, ferrocolumbite, cassiterite and zircon are present. Secondary minerals such as vivianite [Fe3(PO4)2•8H2O], fluorapatite and siderite occur in fractures and vugs. Two textural varieties have been recognised, i). a medium- to coarse-grained pegmatitic fabric composed of quartz, albite, spodumene, K feldspar, and muscovite, and ii). a secondary saccharoidal albite-quartz fabric that replaces the medium- to coarse-grained pegmatite. Variable amounts of the two textures result in a wide range of modal abundance, ranging from granite to quartz diorite. Only spodumene and microcline are commonly >2 cm in length, but are rarely longer than 30 cm. Spodumene and microcline crystals are commonly fractured and the fractures are filled with a sugary matrix of albite and quartz. Yellowish-white muscovite crystals, commonly twisted, are typically <2 cm long. The outer 1 to 50 cm of the spodumene pegmatites are composed of albite and quartz, along with accessory amounts of apatite, chlorite, muscovite and pyrrhotite. The lower absence of spodumene and K feldspar in this border zone is related to the loss of Li and K from the pegmatite and the formation of holmquistite [(Li2)(Mg3Al2)(Si8O22)(OH)2] and biotite in the wallrocks (Swanson, 2012, Horton, 2008).

Spodumene occurs as large, white to light green, subhedral to anhedral fractured crystals which are generally free of inclusions. The spodumene content of individual dykes varies from 5 to 35 vol.% (Griffitts 1954). There is, in some cases, slightly more spodumene toward the centre of the pegmatite dykes (Luster 1977). Edges of the spodumene crystals are typically sharp, although a zone of vermicular spodumene intergrown with quartz or feldspar may well occur in spodumene adjacent to feldspar. Large crystals of spodumene are generally fractured, and in some cases, completely broken into distinct fragments. Fractures in spodumene crystals are typically healed with the fine-grained albite-quartz fabric described above, or, less commonly, with fine-grained muscovite. A reconstruction of fractured crystals reveals an original size of up to 75 cm in length (Hodges 1983). Electron-microprobe analyses show only a small amount of iron (0.2 to 1.1 wt.% FeO) in the spodumene.

Spodumene-bearing Aplite occurs along the margins of medium-grained spodumene pegmatites and as dykes within the pegmatite. They are similar to the secondary saccharoidal albite-quartz described above, and account for <10% of the spodumene bearing rocks of the belt. Layering, defined by a variation in spodumene content, is locally developed in the spodumene bearing aplite, distributed along the contacts with spodumene pegmatites. This layering parallels the contacts, with individual bands typically being a few cm in thickness. Darker layers are coarser-grained (~1 mm), whilst poorly foliated spodumene rocks, and finer-grained (i.e., 0.1 to 0.2 mm) lighter layers are composed of well-foliated spodumene-poor rocks. Variation in the proportion of these dark spodumene rich and light barren layers result in the development of spodumene-rich and -poor aplites. Most of the aplite has a polygonal fabric of quartz and albite, with rare grains of coarser quartz and albite occurring in the spodumene-rich variety. The spodumene-rich aplitic rocks have a similar composition to the medium-grained spodumene pegmatites, with larger grains of quartz, albite and muscovite in a fine-grained matrix of the same minerals. Zones of shearing are parallel to the layering (Swanson, 2012, Horton, 2008).

In addition to the spodumene pegmatites and aplites, other intrusions include spodumene free Coarse-grained Granite/Pegmatite which has been dated at 341±40 Ma (whole-rock Rb-Sr; Kish and Fullagar, 1996). It occurs as swarms of irregular dykes, sills and pods up to a few metres thick near the southeastern contact of the Cherryville Granite which is NW of the Kings Mountain Fault. These intrusions comprise a white, coarse-grained pegmatite, predominantly composed of microcline, oligoclase, quartz, muscovite and biotite. Accessories include euhedral garnet that is as much as 1 cm in diameter, with lesser magnetite-ilmenite, zircon, apatite, beryl and chlorite. The composition is similar to that of the nearby batholithic Cherryville Granite, although muscovite is more abundant and biotite is less so. Where present, large books of mica are un-deformed. Textures include graphic intergrowths of feldspar and quartz, overgrowths of muscovite on biotite, and plumose cones of muscovite intergrown with quartz (Swanson, 2012, Horton, 2008).

Coarse-grained Granite and Pegmatite which are interpreted to be outliers of the Cherryville Granite, occurring as a series of bodies that range from 500 x 150 m to 4 x 1 km in size, elongated parallel to, and both within and immediately to the NW of the Kings Mountain Shear Zone. As such they lie both within the shear zone, and between it and the parallel south-eastern margin of the main Cherryville Granite batholith. These intrusions are also both within, and NW of, the Tin-Spodumene Belt. They are a pale grey, coarse-grained biotite-muscovite granite grading into pegmatite and are crosscut by pegmatite dykes, mainly composed of microcline, oligoclase, quartz, muscovite and biotite, and include graphic granite and weakly foliated textures (Swanson, 2012, Horton, 2008).

Muscovite-biotite Granite, the main Cherryville Granite batholith, which has been dated at 351±20 Ma (whole-rock Rb-Sr; Kish and Fullagar, 1996). It is a very pale grey, medium- to coarse-grained, and weakly foliated granite, composed of microcline, oligoclase, quartz, biotite and muscovite, with accessory magnetite-ilmenite, apatite, zircon, chlorite, epidote and rare beryl (Horton, 2008). Note that Swanson (2012) describes the granite as fine grained. The batholith is composed of hundreds of smaller intrusions, many of them intruded as tabular sheets along the foliation of the host metamorphic rocks. Similar intrusions are widely scattered throughout the Cat Square and eastern Inner Piedmont (Goldsmith et al., 1989).

According to various authors quoted by Dennis et al, (2012), there is an interpreted relationship between the Cherryville Granite and the Spodumene Pegmatites. Field observations suggest a temporal progression from Spodumene Pegmatites → dykes of Cherryville Granite → Cherryville Granite. Stewart (1978), suggests the spodumene pegmatites are the product of anatectic melts of lithium-rich continental meta-sedimentary rocks. This sequence could be interpreted to reflect the progression in the anatexis of the the thick imbricated crust during the Alleghanian Orogenesis.

The main intruded Neoproterozoic to Cambrian age lithologies within the Carolina Tin-Spodumene Belt are as follows:

Amphibolite - a dark grey, fine-grained, equigranular, layered rock composed of plagioclase and hornblende with lesser diopside, calcite, epidote and quartz, with accessory sphene, apatite and pyrrhotite. Biotite and chlorite are present at the boundary with schist layers, whilst calcite-rich layers occur locally (Horton, 2008). According to Swanson (2012), the amphibole, is magnesiohornblende, which does not contain measurable F or Cl. In the contact zone with spodumene pegmatites, the magnesiohornblende is replaced, over a width a few cm, by an acicular amphibole that does not contain any Ca, Na or K, but is higher in silica than the magnesiohornblende. Biotite has subequal amounts of Fe and Mg and does not contain F, whilst fluorapatite is devoid of Fe and Mn.

Muscovite schist - a yellowish-grey, medium-grained, amphibolite-facies schist, predominantly composed of muscovite, quartz, minor biotite, and locally oligoclase. Garnet, staurolite and kyanite are evident locally, whilst secondary chlorite is a common accessory. Muscovite flakes average 2 mm in length and quartz grains average 1 mm in diameter. The weathered schist is greyish pink to pale red. The composition of the schist indicates a pelitic sedimentary protolith. It is coarse grained and quartz-rich proximal to the Cherryville Granite and pegmatites. Radial clusters of tourmaline are common within the schist adjacent to spodumene pegmatite.

A range of pegmatites are evident within the Carolina Tin-Spodumene Belt. These include:

i). Pre-tectonic plagioclase-quartz-muscovite-garnet pegmatites that are folded with the enclosing amphibolite and are barren. However, muscovite and Mn-bearing fluorapatite compositions are similar to that of equivalent phases in the spodumene pegmatites.

ii). Spodumene pegmatites, which show no obvious folding, but are usually sheared, some of it severe, suggesting emplacement near the end of the cycle of deformation. Garnet, which is found in the pre-tectonic dykes, and biotite, as in in the post-tectonic pegmatites, do not occur in the spodumene pegmatites.

iii). Post-tectonic plagioclase-quartz-K feldspar-muscovite-biotite pegmatites, with no obvious evidence of deformation, contain Mn-poor (0.2 to 1.2 wt.% MnO) fluorapatite, and are barren.

Kings Mountain Cluster

The Kings Mountain Mine was developed in a narrower, ~1 km wide, part of the Carolina Tin-Spodumene Belt where there is a local higher concentration of spodumene-bearing pegmatites. The mined pegmatite swarm are developed over a strike length of ~3 km and width of up to 450 m in the NE, tapering to 120 m in the SW. Some of the spodumene pegmatites are emplaced in the Kings Mountain Shear Zone, whilst almost all intrude amphibolite, with just a few transgressing into muscovite schist to the SE (Horton 1981). Barren and spodumene bearing pegmatites and aplites occur in the King Mountain Mine legacy open pit (Kesler 1961, Luster 1977). Gradational contacts between some barren and ore pegmatites suggested to Kesler (1961) a genetic relation between these rocks (Swanson, 2012).

Hallman-Beam Cluster

A more diverse suite of pegmatites is exposed in the Hallman-Beam Mine (Hodges 1983, Spanjers 1990). Barren pegmatites include biotite-muscovite, garnet-bearing, and large beryl-bearing pegmatites (Hodges 1983, Spanjers 1990). Spodumene-bearing rocks include compound layered aplite, medium-grained pegmatite, massive to layered aplite, medium-grained pegmatite and coarse-grained pods of pegmatite enclosed in aplite. A small stock of strongly weathered granite (the 'Mine Granite' of Hodges 1983) is exposed in one corner of the mine. The mine granite has the same assemblage of minerals as barren garnet dykes, but in different proportions. The mine granite has gradational contacts with garnet-bearing pegmatite-aplite dykes, and the albite compositions are similar (Hodges 1983). The pegmatitic texture is commonly replaced by the saccharoidal albite-quartz fabric in the Tin-Spodumene Belt (Swanson, 2012).

Reserves and Resources

The Kings Mountain Lithium deposit Ore Reserves and Mineral Resources as at December 31, 2022 (Albemarle Corporation, Form 10-K Report to the US SEC, 2023) were:

Indicated Mineral Resource - 46.816 Mt @ 1.37% Li2O;

Inferred Mineral Resource - 42.869 Mt @ 1.10% Li2O;

No Ore Reserves have been published.

Resources estimates quoted by Kesler (1976) were:

Kings Mountain Mine - 45.6 Mt @ 0.7% Li;

Hallman-Beam Mine - 62.3 Mt @ 0.67% Li.

The Carolina Lithium Project Mineral Resources as at October 21, 2021, at a cut-off of 0.4% Li2O (Piedmont Lithium Press Release 2021) were:

Indicated Resource

Core Deposit - 25.75 Mt @ 1.10% Li2O;

Central Deposit - 2.47 Mt @ 1.30% Li2O;

Huffstetler Deposit - None.

TOTAL Indicated Resource - 28.22 Mt @ 1.11% Li2O;

Inferred Resource

Core Deposit - 10.93 Mt @ 1.02% Li2O;

Central Deposit - 2.69 Mt @ 1.10% Li2O;

Huffstetler Deposit - 2.31 Mt @ 0.91% Li2O.

TOTAL Inferred Resource - 15.93 Mt @ 1.02% Li2O;

TOTAL Resource - 44.15 Mt @ 1.08% Li2O, with a metallurgical recovery of 71.2%.

The most recent source geological information used to prepare this decription was dated: 2022.

This description is a summary from published sources, the chief of which are listed below.

© Copyright Porter GeoConsultancy Pty Ltd. Unauthorised copying, reproduction, storage or dissemination prohibited.

Kings Mountain Mine

|

|

|

|

|

Dennis, A.J., Shervais, J.W. and LaPoint, D., 2012 - Geology of the Ediacaran - Middle Cambrian rocks of western Carolinia in South Carolina: in Eppes, M.C., and Bartholomew, M.J., (Eds.), 2012 From the Blue Ridge to the Coastal Plain: Field Excursions in the Southeastern United States, The Geological Society of America Field Guide 29, pp. 303-325, doi:10.1130/2012.0029(09).

|

Hibbard, J.P., Pollock, J. and Bradley, P., 2013 - One arc, two arcs, old arc, new arc: an overview of the Carolina terrane in central North Carolina: in Hibbard, J.P. and Pollock, J. (Eds.), 2013 Carolina Geological Society Annual Meeting and Field Trip, November 8-10, 2013, Salisbury North Carolina, pp. 35-61.

|

Horton, J.W., 2008 - Geologic Map of the Kings Mountain and Grover Quadrangles, Cleveland and Gaston Counties, North Carolina, and Cherokee and York Counties, South Carolina: in U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Map 2981, 1 sheet, scale 1:24,000, with 15-p. pamphlet. 19p.

|

Swanson, S.E., 2012 - Mineralogy of Spodumene pegmatites and related rocks in the Tin-Spodumene belt of north Carolina and south Carolina, USA: in The Canadian Mineralogist v.50, pp. 1589-1608

|

Thigpen, J. R., Moecher, D. P., Stowell, H. H., Merschat, A., Hatcher, Jr, R. D., Powell, N. E., Spencer, B.M., Mako, C.A., Bollen, E.M. and Kylander-Clark, A., 2022 - Defining the Timing, Extent, and Conditions of Paleozoic Metamorphism in the Southern Appalachian Blue Ridge Terranes of Tennessee, North Carolina, and Northern Georgia: in Tectonics v.41, 28p. doi.org/10.1029/2022TC007406.

|

|

Porter GeoConsultancy Pty Ltd (PorterGeo) provides access to this database at no charge. It is largely based on scientific papers and reports in the public domain, and was current when the sources consulted were published. While PorterGeo endeavour to ensure the information was accurate at the time of compilation and subsequent updating, PorterGeo, its employees and servants: i). do not warrant, or make any representation regarding the use, or results of the use of the information contained herein as to its correctness, accuracy, currency, or otherwise; and ii). expressly disclaim all liability or responsibility to any person using the information or conclusions contained herein.

|

Top | Search Again | PGC Home | Terms & Conditions

|

|