|

Kamoa and Kakula |

|

|

Katanga, Dem. Rep. Congo |

| Main commodities:

Cu

|

|

|

|

|

|

Super Porphyry Cu and Au

|

IOCG Deposits - 70 papers

|

All papers now Open Access.

Available as Full Text for direct download or on request. |

|

|

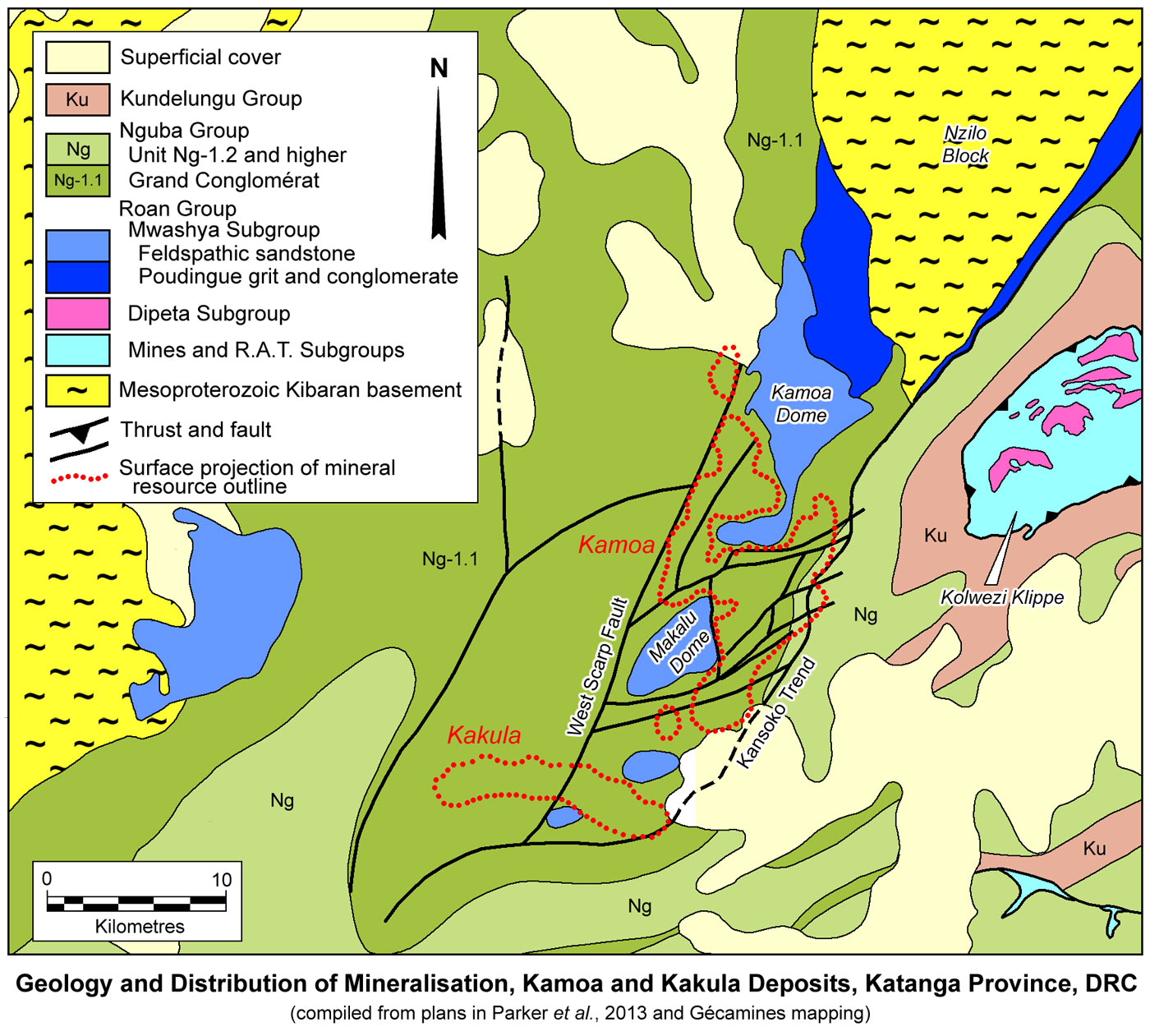

The Kamoa and Kakula sediment hosted copper deposit lies on the western margin of the Central African Copperbelt, in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), ~25 km west of Kolwezi and 270 km west of the provincial capital of Lubumbashi (#Location: 10° 46'S, 25° 15'E). Kakula is ~5 km SW of the southern tip of Kamoa.

Regional Setting

For details of the regional setting of the Kamoa and Kakukla deposits, the Central African/Congolese Copper Belt and the Lufilian Arc, see the Central African Copperbelt - Congolese/Katangan Copperbelt record.

Geology

The Kamoa deposit occurs on a gently folded shelf, overlying a regionally NNE-trending, generally south-plunging basement block that outcrops <10 km to the NNE as the NNE-SSW trending Nzilo Block, composed of Kibaran (1.3 to 1.1 Ga) metasedimentary rocks.

Aeromagnetic data defines a major NNE-SSW trending feature, the ~3 km wide Kansoko Trend, that appears to define the eastern margin of both the Kamoa deposit, and the Nzilo Block. This trend is underlain by a thick, 15 to 21° easterly-dipping sequence of weakly carbonaceous and pyrrhotite-bearing diamictite and siltstone, with subordinate andesitic/mafic sill-like bodies to the NE. It is interpreted to represent a major syn-depositional fault zone that has been subsequently reactivated, and now occurs as an east-dipping monocline (Schmandt et al., 2013; Hitzman et al., 2012). It also marks the approximate boundary between a thick, deformed, eastern basinal sequence, comprising well developed Roan Group carbonate and siliciclastic rocks, and a western, shallow-dipping and condensed, siliciclastic sequence of Mwashya Subgroup rocks of the upper Roan Group, unconformably draping onto basement on the basin rim (the Western Foreland of Key et al., 2001).

The western edge of the Kamoa deposit is bounded (or downfaulted) by the west-side-down West Scarp normal fault (and magnetic feature), with a vertical displacement of 350 to 400 m. This fault also apparently corresponds to the western margin of the exposed Nzilo block, although it does not appear to have been active during deposition of the upper Mwashya Subgroup and lower Nguba Group (Schmandt et al., 2013). It marks the eastern margin of a deep graben (or half graben) that has preserved a thick section of the diamictite of the basal Nguba Group Grand Conglomérat and associated sedimentary rocks, which dip at <10° to the west and south.

Within the Kamoa deposit area there are a number of curved, but generally ENE-WSW trending faults with minor, generally <10 m of normal offset to the south, some of which may have been active during Katangan deposition.

Kamoa therefore, overlies a present day NNE-SSW elongated horst that is ~7 to 9 km wide, located along the western edge of the Katangan basin. The host sequence over the horst represents a broad, undulating plateau, punctuated by a series of gentle domes (including the main Kamoa and Makalu domes), where the Grand Conglomérat has been eroded, and the underlying Mwashya Subgroup sandstones are exposed (Schmandt et al., 2013; Parker et al., 2013).

The NNE-SSW elongated Makalu Dome, in the south, covers an area of ~7.5 x 3 km, while the southern lobe of the dumbbell shaped Kamoa dome, 3 km to the NNE, is 4 x 1.5 km, aligned east-west, connected on its northeastern edge by a narrow NNE-SSW neck, to a larger north-south elongated, 10 x 8 km window to the north. The indicated + inferred resource outline of the Kamoa deposit covers an area of ~22 x 12 km, that extends from the southern tip of the Makalu dome, along its eastern margin, reaching its maximum width between the two domes, surrounding the southern half of the Kamoa dome and then extending up the western margin of the northern lobe of the Kamoa dome to taper near that structures northern extremity (2013; Parker et al., 2013).

These domes are windows, exposing the redox boundary between the underlying hematitic (oxidised) Mwashya Subgroup sandstones in the core of the structures, and the overlying carbonaceous and sulphidic (reduced) Grand Conglomérat, the host to mineralisation, which dips outward from the domes at ~5°.

Syn-depositional growth faults are evident within the deposit area which have markedly influenced the thickness of the host sedimentary rocks and the deposition of copper mineralisation. A particular example is the NNW-SSE Mupaka Fault that defines the eastern margin of the Makalu Dome. This structure and it influence on the thickness of the host sequence will be discussed below.

The deposit was developed where the thick Katangan sequence markedly thinned as it draped onto the basin margin, in a manner somewhat analogous to the Roan Group pinch-out onto the margin of the Kafue anticline basement high in the Zambian Copperbelt (see the Zambian Copperbelt record).

The host sequence and basement at Kamoa are autochthonous, located just beyond the outer edge of the mainly allochthonous to para-allochthonous External Fold and Thrust Belt of the Lufilian Arc (as at Kolwezi, 25 km to the east) that was transported north during the Lufilian orogeny, to overlie the Western Foreland (see the Congolese Copperbelt record). While the NNE-SSW aligned Kansoko Trend may have represented a growth fault during deposition of the Katanga Supergroup, it may also have been re-activated as a transfer fault, accommodating differential displacement during the later Lufilian orogenesis, separating autochthonous rocks to the west, from the north directed transport of the allochthonous External Fold and Thrust Belt to the east.

The geological sequence in the Kamoa district is as follows, from the base (after Schmandt et al., 2013; Parker et al., 2013):

The geological sequence in the Kamoa district is as follows, from the base (after Schmandt et al., 2013; Parker et al., 2013):

Kibaran basement - quartzite, weakly metamorphosed ferruginous siltstone and greywacke, sandstone, and minor mafic rocks, carbonaceous phyllite,

and dolostone, as exposed to the north of Kamoa within the Nzilo block, deposited between 1380 and 1370 Ma (François, 1973; Kokonyangi et al., 2006; Broughton and Rogers, 2010 Tack et al., 2010; Schmandt et al., 2013).

angular unconformity

Roan Group (R-4) - which was deposited post 880 Ma, is well developed to the east in the Kolwezi klippe and Tenke-Fungurume Roan window, where it is over 1500 m thick and comprises, from the oldest unit, the R.A.T. Subgroup (R-1), oxidised, purple to red, chloritic and dolomitic detrital sedimentary rocks; the Mines Subgroup (R-2), interbedded reduced and evaporitic stromatolitic dolostone, dolomitic siltstone and argillites containing the bulk of the Cu-Co ores in its lower sections, immediately above the R.A.T.-Mines subgroups redox boundary; the overlying Dipeta Subgroup (R-3), which is lithologically similar, but generally barren; and the uppermost Mwashya Subgroup (R-4), largely composed of dolomitic silty shales/siltstones/sandstones, grey to black, pyritic carbonaceous shales and an upper suite of pink to green feldspathic sandstone, arkose or conglomeratic arkose, alternating with variable amounts of shale or siltite.

At Kamoa, however, only the Mwashya Subgroup (R-4), is represented, varying from several tens to several hundreds of metres in thickness, made up of the following:

• Poudingue (Roan Grit and Conglomerate), (R-4.1), which rests unconformably on Kibaran basement quartzite to the north. It includes thin to >10 m thick conglomerate bands within pebbly, angular grit and sandstone beds, in a sequence that is typically immature and poorly sorted, with the exception of some conglomerate bands that have a weak feldspathic cement.

• Roan Feldspathic Sandstone, (R-4.2) - compositionally and texturally immature feldspathic sandstones, arkoses and silty arkosic greywacke, which are massive to very coarsely bedded, with beds ranging in thickness from centimetres to several metres. The feldspathic sandstones/greywackes are composed of rounded to subangular grains of quartz and feldspar, commonly with quartz overgrowths, cemented with intergranular quartz and fine-grained muscovite, chlorite and biotite, sometimes containing rare pyrite. They are often gritty and pebbly, with some diffuse, relatively fine-grained conglomeratic bands (≤1m thick), containing pebbles that are generally <1 cm in diameter and dominantly comprise quartz with lesser basement schist and gneiss, basalt, sandstone and limestone. Very fine-grained sandstone, thin dark-coloured, biotite-rich, non-pyritic laminated siltstones and thin hematitic silty bands, with irregularly developed undulating and anastomosing laminae, are locally interbedded with the greywackes, but account for <5% of the unit. The greywackes are normally well cemented, although the top 1 to 5 m below the mineralised diamictite, is often friable and porous, with obvious weathering of feldspar and dissolution of probable dolomite, accompanied by kaolinisation, mostly due to secondary, geologically recent, processes. Symmetric and asymmetric ripples, trough cross bedding, planar stratification and water escape structures are evident to varying degrees, and beds both fine and coarsen upward. These high and low energy traction current sedimentary structures, occasional pebble conglomerates and the compositional immaturity, suggest deposition in a marginal marine to possibly subaerial fluvial environment (Parker et al., 2013).

Nguba Group (Ng) - commencing with the Grand Conglomérat (Ng-1.1) - which overlies the Mwashya Subgroup sediments across a sharp contact, suggesting erosion of the underlying, poorly lithified Mwashya Subgroup sediments. This contact also represents a sharp redox boundary between the underlying hematitic Mwashya Subgroup and the reduced Grand Conglomérat, and exerts a major control on copper sulphide precipitation (Broughton and Rogers, 2010). The Grand Conglomérat comprises:

• Basal Diamictite Package, (Ng-1.1.1), which is the main host for the Kamoa copper orebody. This package shows an abrupt thickness change from 40 to 120 m thick in the SW, to 3 to 35 m thick in the NE, across the Mupaka fault, a NNW-SSE structure that also marks the ENE margin of the Makalu Dome (see figure above). This package is made up of the following three subunits:

- Lower basal diamictite (Ng-1.1.1.1) - 5 to 25 m thick, composed of olive, maroon, and pale grey diamictite containing an average of 20 to 35% pebble sized clasts. It is poorly mineralised, with a sandy base, and pinches out east of the Mupaka fault, but thickens to as much as 40 to 80 m to the west of the fault. In the northeastern part of the Kamoa deposit, it varies from 1 to 5 m in thickness; while in the east-central part of the deposit it is absent or thinner; and varies from 5 to 20 m thickness below the centre of the deposit. The pebbles and larger clasts are sub-angular to sub-rounded but are generally <10 cm across, with the exception of large mafic igneous clasts that may be up to 50 cm in diameter. The clasts comprise poorly sorted quartzite, quartz, mafic igneous rock and sandstone. Hematitic matrix, commonly occurs just above the contact between underlying Roan Group sandstone, representing a maroon oxide facies. The quantity of large clasts and their sizes within this subunit vary from 25 to 35% of the sediment east of the Mupaka fault to between 7 and 15% to the west where the differentiating between the lower and the upper basal diamictite subunits is difficult. West of the Mupaka fault, the amount of intermediate siltstone/sandstone layers in the basal diamictite increases significantly (Twite et al., 2019; Parker et al., 2013).

- Intercalated siltstone/sandstone unit (Ng-1.1.1.2), which is primarily composed of interbedded olive, grey to dark grey siltstone and sandstone

with local small-pebble conglomerate bands. It is generally well mineralised, but discontinuously distributed, and absent or <2 m thick to the NE of the Mupaka fault, abruptly thickening to 5 to 20 m to its west (Twite et al., 2019).

- Upper basal diamictite (Ng-1.1.1.3), composed of medium to dark olive-grey diamictite with an argillaceous, silty, chloritised matrix and is generally well mineralised. It generally contains 10 to 20% pebble-sized clasts composed of unsorted quartzite, argillite and mafic clasts that range from 2 to 10 cm in diameter. Its thickness varies from 3 to 15 m to the east of the Mupaka fault and up to 30 to 60m thick to the west, where it is intercalated with siltstone and sandstone layers. It contains good reductants which catalyse precipitation of copper and is key to the resource (Twite et al., 2019).

It is uncertain, from the source literature, as to how much pre-ore diagenetic pyrite was present within the Basal Diamictite Package (Ng-1.1.1), which hosts the bulk of the post-diagenetic, hydrothermal copper sulphide deposit. The overlying units (Ng-1.1.2 to 1.1.4) contain substantial early diagenetic pyrite, both as fine framboidal and secondary cubic pyrite. Copper sulphides are observed to replace framboidal pyrite in Ng-1.1.1, where unreplaced cores remain, while diagenetic pyrite and copper sulphides of the orebody display overlapping isotopic values, suggesting the latter inherited reduced sulphur from earlier formed diagenetic pyrite (Schmandt et al., 2013). Consequently, it seems likely, the Basal Diamictite Package (Ng-1.1.1) also contained significant diagenetic pyrite prior to ore deposition.

A 30 to 50 mm thick, thinly laminated mudstone drapes over the top of the Basal Diamictite Package, separating it from the overlying Ng-1.1.2 with a generally sharp contact. It is a distinctive marker horizon across the central portion of the deposit, and is composed of 1 to 3 mm thick, alternating pale and dark grey laminations made up of mud, composed mostly of fine-grained quartz (up to 20 µm), with abundant shale pellets, and lacks diagenetic pyrite (Twite et al., 2019; Parker et al., 2013).

• Kamoa Pyritic Siltstone-Sandstone (Ng-1.1.2), comprises pale to medium grey and greenish-black, laminated to bedded mudstone/siltstone with local large clasts, and intercalated sandstone layers with a mixture of massive, thickly bedded and small-pebble conglomerate bands. This unit locally contains diamictite with 5 to 15%, pebble-sized clasts to the NE, thickening abruptly across the Mupaka fault, from 0 to 15 m in the east, to 40 m west of the structure (Twite et al., 2019). According to Parker et al. (2013), the lower section of the Kamoa Pyritic Siltstone-Sandstone unit, above the thinly laminated mudstone marker, is predominantly well stratified and laminated, containing bedded pyrite. The lower contact with the basal diamictite is frequently characterised by a thin, <20 cm, clast-supported quartzitic conglomerate. This unit contains 5 to >25% pyrite, both as very fine grained, framboidal disseminations, and as secondary, very coarsely recrystallised, subhedral to euhedral crystals. The lowermost 3 to 5 m generally contains only fine grained pyrite, but it may also locally host copper mineralisation

• Middle Diamictite Package (Ng-1.1.3) - is generally a medium-to dark grey diamictite with 20 to 40% pebble-size or larger clasts that usually range between 2 and 200 mm across, rarely in the 50 to 200 cm range, with a thickness varying from 150 to 250 m. However, in contrast to the preceding units, there is no abrupt thickness changes across the Mupaka Fault (Twite et al., 2019). The clasts are frequently dominated by quartzite, very fine-grained sandstone, shale and black argillite, very variable amounts of mafic rocks (mainly dolerite), with subordinate vesicular lava, quartz and scattered granitic and schistose basement cobbles. Coarse feldspathic sandstone clasts are rare and tend to be preferentially weathered. Rare clasts of Roan dolomite have also been recorded (Parker et al., 2013).

• Upper Laminated Pyritic Siltstone (Ng-1.1.4) is similar to the Kamoa Pyritic Siltstone-Sandstone (Ng-1.1.2), composed of pale, medium to greenish-grey, laminated pyritic siltstone with intercalations of pale-grey sandstone and minor small-pebble conglomerate, and varies from 5 to 25 m in thickness, with no obvious variation across the Mupaka Fault (Twite et al., 2019).

• Upper Diamictite Unit (Ng-1.1.5) - which is farthest removed from mineralisation and the least altered diamictite in the deposit area. It is composed of pale greenish-grey diamictite, with 7 to 15% pebble sized or larger clasts of quartzite, mafic rock, argillite that range from 5 to 50 mm across. It has a matrix of quartz, chlorite, plagioclase, potassium feldspar, mica (muscovite and biotite), carbonate minerals (calcite and minor ankerite) and minor heavy minerals (tourmaline, rutile, apatite), with minor disseminated pyrite. Clasts are similar to those of the Middle Diamictite. The unit ranges from 200 to 350 m in thickness and is intercalated with thick layers of sandstone and siltstone.

• Uppermost Diamictite Unit (Ng1.1.6) - that commences with a basal, 0.5 to 15 m thick sandstone bed, overlain by pale greenish-grey

diamictite with 7 to 20% pebble-sized or larger (5 to 150 mm) clasts of quartzite, mafic rock and argillite, intercalated with thick conglomerate, sandstone, and siltstone beds. It is only preserved in the deepest drill holes in the central, eastern and northern parts of the deposit, having been eroded eroded near the domes. Overall it's composition is similar to that of the upper diamictite, Ng-1.1.5 (Twite et al., 2019).

Igneous activity that is temporally and spatially associated with the host sequence includes, basaltic flows, pillow breccias and hyaloclastite breccias, together with gabbroic and doleritic textured mafic igneous rocks, occurring both within the Mwashya Subgroup and the base of the Grand Conglomérat, directly northeast of the Kamoa deposit (Schmandt et al., 2013). These are described as one or more, 5 to 80 m thick, apparently concordant tabular bodies, which may be sills or flows, in the Kansoko Trend to the north of the deposit, and as >200 m of vesicular to massive, brecciated and altered, pale green to light grey-green lava grading into a fine-grained igneous rock, probably of andesitic composition, encountered in drilling adjacent to the deposit (Parker et al., 2013).

Diamictite units represent the most volumetrically abundant lithofacies in the Grand Conglomérat at Kamoa, and vary from 10 to 300 m in thickness, with strike lengths in excess of several kilometres. Clasts range from ~2 mm to 3 m in diameter and from well rounded to angular. They include exotic lithologies such as quartzite, quartz-mica schist, phyllite, limestone, dolostone, argillaceous dolostone and gabbro as well as locally derived basalt, Mwashya Subgroup greywacke, and Grand Conglomérat siltstone, greywacke and diamictite. The matrix is composed of silt (2.5 to 20 µm) that varies from light to dark grey or grey-green in colour (Schmandt et al., 2013).

NOTE: Whilst most previous workers have concluded that the Grand Conglomérat had a glacio-marine origin (e.g., Binda and Van Eden, 1972; Selley et al., 2005; Wendorff and Key, 2009; Master and Wendorff, 2011), Kennedy et al. (2018), working with drill core from the Kamoa area, suggest that it is not composed of tillites and do not record an ice-contact. Instead they are interpreted as mass flow (debrites) within a thick, but <3 km thick succession of genetically-related sedimentary gravity flow facies composed of olistostromes, slumps and turbidites deposited in deep-water within a rapidly subsiding rift basin.

Steeply dipping bedding, soft-sediment deformation and syn-sedimentary mesoscopic faults with offsets of millimetres to centimetres are common within the diamictites throughout the Kamoa area, particularly in lithologies in close proximity to the Mupaka fault, e.g., steep bedding near this fault in one drill hole strikes NNW-SSE, in contrast to the typical regional NNE-SSW bedding trend. The orientation of the Mupaka fault is oblique to the trend of the domes and coincides with an area of elevated copper grade as discussed later. Slump folds and minor mesoscopic faults are generally subvertical in sub-horizontal beds adjacent to the steep bedding, while they are gently-dipping in steep bedding (Twite et al., 2019). Twite et al. (2019) suggest these structures predate the tilting of bedding, which they suggest is related to movement on the Mupaka growth fault.

Framboidal and secondary pyrite in diamictites are most common low in the Grand Conglomérat and probably largely grew in situ, although some may be detrital grains derived from erosion of underlying pyritic sediments (Schmandt et al., 2013).

Sedimentary structures and the matrix-supported nature of the diamictites, suggest deposition by mass transport or sediment gravity flow processes, e.g., slumping and debris flow, while rare graded beds indicate occasional turbidity currents (Schmandt et al., 2013).

Dark grey to grey lithic greywacke lenses are irregularly interbedded through all of the diamictite packages, and range from ~3 to 30 m in thickness, extending discontinuously over strike lengths up to 3 km, though most persist for <1 km along strike. They generally have sharp lower and gradational upper contacts with diamictite, and are composed of silt to pebble size (3 µm to 2 cm) grains and clasts, with grains that average 0.2 to 1 mm of mainly quartz, with lesser feldspar and carbonate (calcite and ankerite) minerals. Sedimentary structures indicate deposition by turbidity currents, while their geometry suggests deposition in channels or between diamictite lobes, derived from glacial outwash flows or from reworking of unlithified diamictite (Schmandt et al., 2013).

Two similar laminated pyritic siltstone units (Ng 1.1.2 and Ng 1.1.4) within the Grand Conglomérat sequence, are continuous across the deposit area, and range from 2 to 40 m in thickness. Individual laminae vary from millimetres to centimetres and are planar laminated or massive, and normally or reverse graded, with occasional asymmetric and symmetric ripples. They are interpreted to have been deposited by turbidity currents. They include intervals with minor millimetre to a few centimetres thick interbeds of sandstone or conglomerate and diamictite beds up to 15 cm thick. The laminated pyritic siltstones are composed of quartz, pyrite, K feldspar, chlorite, carbonate (ankerite >>dolomite), muscovite and biotite, while interbedded sandstones comprise quartz grains cemented by ankerite. Pyrite is abundant throughout the laminated siltstones, particularly in coarser grained graded beds, with some bands containing >60 vol.% pyrite, mostly framboidal, ranging from <2 to ~20 µm, averaging 5 to 10 µm. Secondary diagenetic pyrite overgrows pyrite framboids, and is mostly cubic, occasionally up 5 mm in diameter, and often concentrated in distinct, cm-scale layers. Rip-up clasts of siltstone within overlying diamictite layers commonly contain framboidal pyrite, indicating pyrite precipitation during early diagenesis (Wilkin et al., 1996; Schmandt et al., 2013).

The Katangan rocks in the Kamoa area contain chlorite, and are weakly metamorphosed to lower greenschist facies.

Kakula - At Kamoa, the deposit is located in a broadly folded terrane centred on the Kamoa and Makalu domes between the West Scarp Fault and Kansoko Trend. At Kakula, the deposit is also located in a broadly folded terrane, but with the central portions of Kakula, and Kakula West, located on the top of the antiforms. Two domes result in erosional windows exposing the redox boundary between the underlying oxidised hematitic Roan sandstones, and the overlying reduced carbonaceous and sulphidic Grand Conglomérat diamictite, the host to mineralisation (Peters et al., 2018).

Peters et al. (2018) discuss the differences between the stratigraphic sections at Kamoa and Kakula, as follows: .. At Kakula, as at Kamoa, sandstones of the Mwashya Subgroup of the Roan Group (R4.2) form the basal unit. At Kamoa, the basal clast-rich diamictite (Ng1.1.1.1) and an upper clast-poor diamictite (Ng1.1.1.3) are clearly distinguished by a variably developed intermediate siltstone (Ng1.1.1.2) sometimes separating them. The distinction of two diamictites at Kakula is not as clear. The diamictites of the Ng1.1.1 are generally clast poor and are typically more silty, suggesting that Kakula represents a more distal depositional environment relative to Kamoa. At Kakula, numerous siltstones are developed within the Ng1.1.1, especially in the lower half of the unit. These siltstones appear to be broadly continuous, although there is no clear correlation between any specific siltstone at Kakula and the intermediate siltstone (Ng1.1.1.2) recognised at Kamoa. A key lithological unit recognised at Kakula is a laterally-continuous basal siltstone, developed just above the R4.2 contact. The basal siltstone is separated from the R4.2 contact by a narrow (often 1 m thick), yet persistently developed, clast-rich diamictite.

In the central portions of Kakula, a strong correlation is evident between the presence of the basal siltstone developed within the Ng1.1.1 and the development of high-grade mineralisation. The vertical thickness of the basal siltstone is thickest in the shallowest parts of the deposit, with a very strong alignment along a trend striking approximately 120°. At Kamoa, there is a general thickening of stratigraphic units to the south-west. However, at Kakula, the Kamoa Pyritic Siltstone-Sandstone Ng1.1.2 (or KPS) is much thinner. Thickening of the KPS in the central portions of Kakula occurs along the same 120° trend, although it is offset relative to the thickening observed in the basal siltstone. Complicated sedimentation patterns are evident in the western section of the Kakula deposit due to proximity to the north-east trending extensional faults active during sedimentation (Peters et al., 2018).

At Kakula, as at Kamoa, the narrow (<3 m) clast-rich diamictite immediately above the Roan contact is only weakly reducing and thus low grade. However, the basal siltstone overlying the clast-rich diamictite is a very strong reductant and accounts for the majority of very high grades (i.e., >6% Cu). The lateral continuity of this reductant allows for the unique continuity of these grades at Kakula. The diamictite overlying the basal siltstone is clast-poor and is also a good reductant; however it hosts low grade mineralisation relative to the basal siltstone (Peters et al., 2018).

Diagenesis and Alteration

At Kamoa, diagenetic minerals occur across the district, throughout the stratigraphy, while hydrothermal minerals are most abundant in and near the ore zone.

Petrography suggests that prior to diagenesis and hydrothermal alteration, the greywackes, siltstones and conglomerates of the Mwashya Subgroup were composed of detrital quartz, feldspar and clay, whilst the Grand Conglomérat diamictites and siltstones were mostly composed of fine-grained rock flour and detrital grains of quartz and feldspar, as well as a variable range of lithic clasts (Schmandt et al., 2013 and references cited therein).

During burial diagenesis at depths of <2 km, and temperatures of <~100°C, they would have undergone recrystallisation of quartz, formation of chlorite from clay, feldspar overgrowths on detrital feldspar, and precipitation of quartz and carbonate cements. With increased burial and temperature, albitisation of feldspar would be expected, together with dolomitisation of calcite. Any external heat input, e.g., the intrusive or extrusive mafic magmatism known in the sequence, or the influx of hydrothermal fluids, could produce an increased temperature gradient and form the deeper assemblages, but at shallower depths (Schmandt et al., 2013 and references cited therein).

In addition to these diagenetic assemblages, the uppermost Mwashya Subgroup rocks and the basal portion of the Grand Conglomérat currently contain significant hydrothermal muscovite, K feldspar and biotite, as well as lesser ankerite, and lack plagioclase or significant calcite. The absence of significant plagioclase and the abundance of potassium feldspar and biotite in these rocks indicate they have undergone potassic alteration. The presence of ankerite suggests relatively high temperature alteration in the presence of reduced pore fluids (Schmandt et al., 2013 and references cited therein).

Hydrothermal alteration occurs in two styles, comprising fine-grained alteration mineral assemblages within the diamictite matrix and prominent rims of coarse-grained minerals surrounding lithic clasts within the Grand Conglomérat diamictites. These coarse grained rims are thickest and most abundant within and proximal to the ore zone within the basal diamictite.

Hydrothermal alteration mineral assemblages at Kamoa are zoned relative to the contact between the Mwashya Subgroup and the Grand Conglomérat, with the most intense alteration and mineralisation occurring at the base of the Grand Conglomérat, indicating that the hydrothermal fluids utilised the underlying Mwashya Subgroup arenitic siliciclastic rocks as an aquifer.

Both the fine and coarse grained mineral assemblages comprise quartz, muscovite, K feldspar, biotite, Mg-rich chlorite, ankerite and sulphides at the base of the mineralised zone, and grade upwards to a suite dominated by calcite and Fe-rich chlorite at the top of the zone of alteration. These assemblages suggest three sequential types of hydrothermal alteration affected the rocks (after Schmandt et al., 2013):

i). potassic - an intense potassic alteration event (accompanied by silicification), which post-dated diagenetic (framboidal) sulphide precipitation, was focused in the lower stratigraphic units of the Grand Conglomérat, and is characterised by an increased abundance and size of K feldspar and biotite in the matrix and in clast/grain rims, as well as the increase in matrix muscovite toward the base of the Grand Conglomérat. These minerals, which are concentrated within and adjacent to the ore zone, are commonly intergrown with Cu sulphides, and hence this event was temporally associated, at least in part, with copper mineralisation. The hydrothermal fluids responsible for copper precipitation had temperatures of ~225°C.

ii). silicification - occurring as coarse grained quartz rims and silicification of clasts toward the base of the Grand Conglomérat, generally coeval with the potassic alteration and Cu sulphides.

iii). magnesian - magnesian chlorite is pervasive throughout the stratigraphic sequence and commonly forms the exterior layer on clast rims, indicating it is paragenetically late, relative to potassic alteration, silicification and most sulphide precipitation. However, overall, this phase produced extensive chlorite alteration at stratigraphically higher levels in the Grand Conglomérat than those affected by the earlier potassic alteration and silicification event. Minor copper mineralisation continued during this phase, as evidenced by chlorite intergrown with copper sulphides.

A later, overprinting, bleached, probably albitic-dolomitic alteration is locally present adjacent to quartz-carbonate-sulphide veins in the west of the deposit, near the West Scarp Fault (Parker et al., 2013).

Mineralisation

Mineralisation at Kamoa is located immediately above the redox boundary at the contact between the oxidised Mwashya Subgroup arenites and the base of the overlying reduced diamictites of the lower Grand Conglomérat, and is capped by the hanging wall Kamoa Pyritic Siltstone-Sandstone (Ng-1.1.2) unit (Schmandt et al., 2013; Parker et al., 2013).

The host sequence comprises several interbedded units that appear to control the distribution of mineralisation. The lowermost clast-rich diamictite unit (Ng-1.1.1.1) is thought to have been only weakly reduced, and generally hosts low-grade (<0.5% Cu) mineralisation throughout. Copper sulphides tend to be most abundant where this unit is thin or absent, such that the overlying reduced units are in direct contact with the underlying oxidised Mwashya Subgroup sandstones. Most of the higher-grade mineralisation occurs within the more strongly reduced clast-poor, carbonaceous and pyritic diamictite unit (Ng-1.1.1.3), or in the intervening sandstone and siltstone (Ng-1.1.1.2) which is frequently absent (Schmandt et al., 2013; Parker et al., 2013).

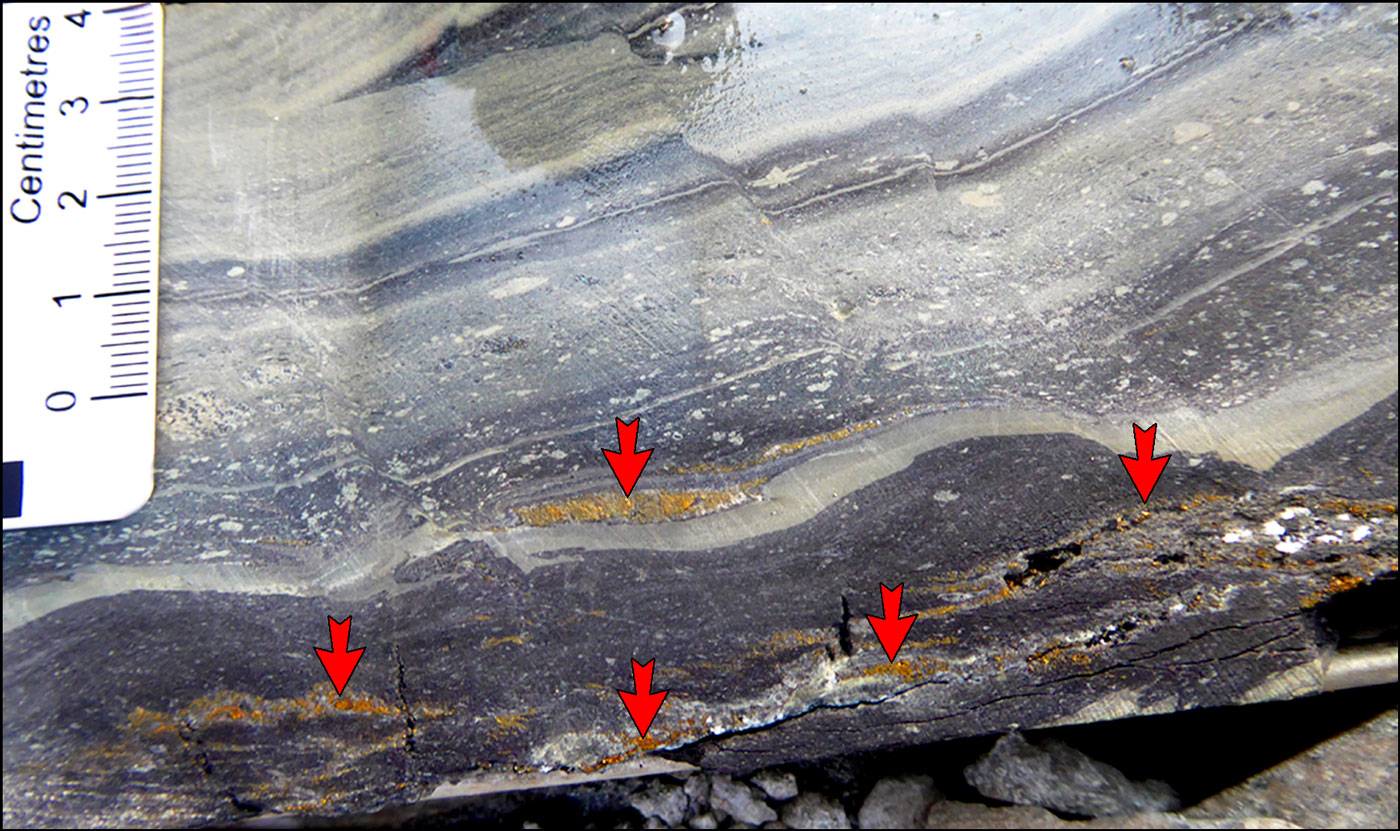

High grade intersection at Kamoa showing lenses of chalcopyrite-bornite (e.g., as indicated by arrowheads) within the weakly deformed host siltstones and reworked glacial sedimentary rocks that constitute the main host in the Grand Conlomérat of the basal Nguba Group. Photograph by Mike Porter.

Sulphide mineralisation was precipitated in two main stages (after Schmandt et al., 2013):

i). the earliest took place during diagenesis, and formed abundant fine framboidal and coarse secondary cubic pyrite, most commonly in the lower units of the Grand Conglomérat, which contains unusually high amounts of early diagenetic framboidal pyrite. This pyrite probably largely grew in situ, and is mostly preserved in the laminated pyritic siltstones and to a lesser extent in some greywacke lenses and diamictites. The coarse, secondary diagenetic pyrite overgrows pyrite framboids, and is mostly cubic, occasionally anhedral, and up to 5 mm in diameter, and is often concentrated in distinct, centimetre scale layers. Framboidal and secondary diagenetic pyrite may be either uniformly distributed within individual beds, or mimic sedimentary structures.

ii). a later period of dominantly hydrothermal copper sulphide mineralisation, which affected the uppermost Mwashya Subgroup rocks, the lower diamictite package (Ng-1.1.1) of the Grand Conglomérat and, locally, the lower siltstone unit, the Kamoa Pyritic Siltstone-Sandstone (Ng-1.1.2). Associated ore stage pyrite is distinguished from diagenetic secondary cubic pyrite by its more anhedral shape as well as its occurrence in mineral rims to lithic grains and clasts. Copper sulphides both overgrow, and replace diagenetic framboidal and secondary cubic pyrite.

δ34S isotopic values from diagenetic pyrite, both framboidal and secondary cubic varieties (-11 to -1‰), closely overlap values for copper sulphides in the lower Grand Conglomérat (-12 to +3‰ with most values between -12 and -5‰). This suggests the copper sulphides inherited reduced sulphur from earlier formed diagenetic pyrite. Inheritance of sulphur during copper sulphide replacement is also supported by the textures of some fine-grained copper sulphides in the diamictite matrix and siltstones that are similar in size and shape to framboidal pyrite. Coarse-grained copper sulphides also share the same light sulphur isotope values, suggesting that they also derived at least some of their reduced sulphur from framboidal pyrite (Schmandt et al., 2013).

However, due to lack of preserved framboidal pyrite, and complete replacement of pre-ore minerals by copper sulphides, Schmandt et al. (2013) suggest petrographic analysis has not been able to demonstrated that the Grand Conglomérat contained a sufficient volume of diagenetic pyrite to account for the observed volumes of both fine- and coarse-grained copper sulphides by the replacement of diagenetic pyrite (c.f., in Michigan, USA - see the separate White Pine record).

Hydrothermal fluids responsible for copper precipitation at Kamoa were moderately saline (~23 to 26 wt.% NaCl equiv.) and had temperatures of ~225°C (Schmandt et al., 2013).

The total thickness of the hypogene sulphide zone at a 1% Cu cutoff, varies from 2 to 15 m. Copper mineralisation occurs as a low grade (generally <1% Cu) sheet over thicknesses that rarely exceed 1 m within the footwall Mwashya Subgroup sandstones, with the bulk of the ore in the overlying Basal Diamictite Package (Ng-1.1.1), as well as locally within the base of the overlying Kamoa Pyritic Siltstone-Sandstone (Ng-1.1.2). The lowermost 3 to 5 m of the Ng-1.1.2 unit may locally host copper mineralisation, but generally only contains pyrite, occurring mainly as very fine-grained, framboidal disseminations, with lesser coarsely recrystallised, subhedral to euhedral grains (Schmandt et al., 2013; Parker et al., 2013).

The principal sulphide minerals within the orebody are chalcocite, bornite, chalcopyrite and pyrite, which share common bedding and replacement textures, ranging from semi-massive accumulations, to disseminations, to very coarse blebs, and occasionally occur as veins. Sulphides commonly mantle and or partially replace clasts in the diamictite (Schmandt et al., 2013).

Copper sulphides are zoned, relative to the Mwashya Subgroup-Grand Conglomérat contact, upward, from chalcocite (Cu2S), through bornite (Cu5FeS4) to chalcopyrite (CuFeS2), then pyrite and, finally, minor sphalerite and/or galena. The upper pyrite zone, locally with abundant sphalerite in its lower sections, commonly extends for hundreds of metres above the copper ore zone, although this is principally early diagenetic, and not hydrothermal pyrite. A similar mineral and elemental zonation occurs laterally outward (Schmandt et al., 2013).

The three copper sulphide species and pyrite form overlapping zones, such that the lower, more copper-rich sulphide generally mantles or partially replaces the overlying, more copper-poor sulphide (e.g. chalcocite mantles bornite in the overlap between these two mineral zones), particularly on the up-section side of clasts in the diamictite, where there may have been more permeability (low-pressure shadow) (Parker et al., 2013; Schmandt et al., 2013).

Copper sulphide mineral zonation is poorly developed below the Grand Conglomérat-Mwashya contact, but is a mirror image of that in the diamictite, with chalcocite and bornite giving way to chalcopyrite and finally pyrite down section. Sphalerite and galena are rarely present. These sulphide zoning patterns suggest that hydrothermal fluids, at least locally, moved laterally along the contact between these two units (Schmandt et al., 2013).

Trace element geochemistry (Schmandt, 2012) indicates that minor enrichment of Pb and Co occur at the outer/upper edge of the main copper zone, in the Grand Conglomérat, although the Co appears to be contained within pyrite. The overall outward metal zoning pattern is Cu-Co-Pb-Zn. Unlike the other deposits in the Congolese Copperbelt, Kamoa is not known to contain carrollite, and the overall Co content in ore samples rarely exceeds several hundred ppm (Schmandt et al., 2013; Parker et al., 2013).

Chalcocite, bornite and chalcopyrite constitute between 5 to almost 15 vol.% of the rock in the ore zone, occurring as both i). very fine grained (<50 µm) disseminations, usually anhedral and equidimensional, distributed throughout the diamictite matrix and ii). coarse-grained crystals that rim, or partially to completely replace clasts, particularly those of mafic igneous rocks. These rimming sulphide minerals are generally anhedral and may form crystals up to 5 cm in length, although they generally represent <10% of the total sulphide content of the rocks. Sphalerite and galena occur stratigraphically above well-developed copper sulphide zones, with textures that mimic those of the copper sulphides (Schmandt et al., 2013; Parker et al., 2013).

Similar sulphide mineral assemblages are generally recognised in both styles at a particular location, and are intergrown with a similar suites of alteration minerals. These relationships suggest that both the fine disseminated and coarse-grained 'rim' sulphides were precipitated simultaneously. Vein-hosted sulphide minerals are rare to absent at Kamoa. Coarse-grained sulphides in rims to lithic clasts within the lower diamictite are often intergrown with and locally appear to replace chlorite, biotite, potassium feldspar, quartz and ankerite (Schmandt et al., 2013).

Sulphides are preferentially distributed along the coarser-grained, more permeable layers within the basal greywacke lenses (Parker et al., 2013).

Throughout much of the deposit, there is a sharp increase from <0.5% Cu to >1% Cu at the top and bottom of continuous zones grading >1% Cu, representing a natural cut-off (Parker et al., 2013).

Compared to Kamoa, where chalcopyrite dominates, the Kakula deposit has a different style of mineralisation. Whilst the vertical hypogene zonation is still evident at Kakula, the chalcopyrite and bornite zones are very narrow, with a very gradual transition downward from bornite to chalcocite, followed by a zone (typically within the basal siltstone) that is chalcocite-dominant. Whilst still dominantly fine-grained, numerous examples of coarse to massive chalcocite are evident in the highest-grade intersections (Peters et al., 2018).

Supergene enrichment has taken place below a leached cap, where the Kamoa ore zone intersects the present day surface, over a strike length of several kilometres. The leached cap has a vertical thickness of ~10 to 50 m, generally ~30 m, and contains only trace amounts of copper within a vuggy zone where feldspar has been altered to clay. Supergene chalcocite, which mantles iron-bearing sulphides (chalcopyrite and pyrite), is accompanied by minor native copper and cuprite. It defines a supergene-enriched zone that extends to depths of ~100 m below the surface, but locally to as much as 250 m, and to ~400 m within fracture and fault zones, and along the basal diamictite-sandstone contact. The main supergene ore mineral chalcocite, overprints, replaces and upgrades the hypogene chalcocite, bornite and chalcopyrite zones of the dipping hypogene orebody, with a mixed supergene-hypogene interface. Cuprite (Cu2O) is uncommon, and occurs as tiny specks and blebs in contact with supergene chalcocite, and as fracture fillings and along rare bedding planes, most commonly just above the top of the Mwashya Subgroup sandstones. Native copper occurs as crystalline plates along oxidised joints and occasionally as specks and veinlets, particularly within a few decimetres above the top of the Mwashya Subgroup sandstones. It commonly replaces chalcocite in this position, and has been found as bedding-parallel veinlets in siltstone and replacement blebs in weathered basal diamictite. Grades of >5% Cu are common within supergene zones. Malachite, azurite, chrysocolla and libethenite occur locally, mostly in fractures related to faults and joints, and as a weathering product of supergene chalcocite (Parker et al., 2013; Schmandt et al., 2013).

Ore Reserves and Mineral Resources

Published NI 43-101 compliant mineral resources as of January, 2013 (Ivanplats website, 2013), applying a 3 m thickness cutoff, and different grade limits, were:

1% Cu cutoff

indicated resources - 739 Mt @ 2.67% Cu;

inferred resources - 227 Mt @ 1.96% Cu.

2% Cu cutoff

indicated resources - 550 Mt @ 3.04% Cu;

inferred resources - 93 Mt @ 2.64% Cu.

3% Cu cutoff

indicated resources - 224 Mt @ 3.85% Cu;

inferred resources - 19 Mt @ 3.04% Cu.

Mineral Resource estimates at March 31, 2018 were as follows (Peters et al., 2018) at a 1% Cu cut-off:

Kamoa

indicated resources - 759 Mt @ 2.57% Cu, over 50.7 km2 and 5.5 m average thickness;

inferred resources - 202 Mt @ 1.85% Cu, over 19.4 km2 and 3.8 m average thickness;

Kakula

indicated resources - 585 Mt @ 2.92% Cu, over 50.7 km2 and 10.8 m average thickness;

inferred resources - 113 Mt @ 1.9% Cu, over 5.5 km2 and 7.3 m average thickness.

Combined

indicated resources - 1340 Mt @ 2.72% Cu, over 70.1 km2 and 6.9 m average thickness;

inferred resources - 315 Mt @ 1.87% Cu, over 24.9 km2 and 4.6 m average thickness.

At a 3% Cu cut-off, the Kakula Indicated Resource is 174 Mt @ 5.62% copper.

NOTE: As of mid 2018, the eastern boundary of the Mineral Resources at Kamoa was defined by the limit of drilling. The deposit is more steeply dipping on this margin, with intersections at depths ranging from 600 m to 1560 m along a strike length of 10 km. Some of the best grade-widths of mineralisation occur here, and in addition, high-grade bornite dominant mineralisation is common. Beyond these drillholes the mineralisation and deposit are untested, and open to expansion. At Kakula, the western and south-eastern boundaries of the high-grade trend within the Mineral Resources are defined solely by the current limit of drilling. Exploration drilling is ongoing in these areas, and there is excellent potential for discovery of additional mineralisation (Peters et al., 2018).

Information in this summary has in part been taken from "Parker et al., March 2013, Kamoa Copper Project, Katanga Province, Democratic Republic of Congo, NI 43-101 Technical Report on Updated Mineral Resource Estimate", prepared for Ivanplats Limited. updated from "Peters et al., March 2018, Kamoa-Kakula 2018 Resource Update", an NI 43-101 Technical Report, prepared by OreWin Pty Ltd for the Kamoa-Kakula Project partners.

The most recent source geological information used to prepare this decription was dated: 2012.

Record last updated: 9/2/2019

This description is a summary from published sources, the chief of which are listed below.

© Copyright Porter GeoConsultancy Pty Ltd. Unauthorised copying, reproduction, storage or dissemination prohibited.

|

|

|

|

|

Broughton, D.W. and Rogers, T., 2010 - Discovery of the Kamoa copper deposit, Central African Copperbelt, D.R.C.: in The Society of Economic Geologists, Special Publication, 15, pp. 287-297.

|

Hitzman, M.W., Broughton, D., Selley, D., Woodhead, J., Wood, D. and Bull, S., 2012 - The Central African Copperbelt: Diverse Stratigraphic, Structural, and Temporal Settings in the Worlds Largest Sedimentary Copper District: in Hedenquist, J.W., Harris, M. and Camus, F., 2012 Geology and Genesis of Major Copper Deposits and Districts of the World - A tribute to Richard H Sillitoe Society of Economic Geologists Special Publication 16, pp. 487-514.

|

Schmandt D, Broughton D, Hitzman M W, Plink-Bjorklund P, Edwards D, Humphrey J, 2013 - The Kamoa Copper Deposit, Democratic Republic of Congo: Stratigraphy, Diagenetic and Hydrothermal Alteration, and Mineralization: in Econ. Geol. v.108 pp. 1301-1324

|

Turner, E.C., Dabros, Q., Broughton. D.W. and Kontak, D.J., 2023 - Textural and geochemical evidence for two-stage mineralisation at the Kamoa-Kakula Cu deposits, Central African Copperbelt: in Mineralium Deposita v.58, pp. 825-832. doi.org/10.1007/s00126-023-01165-z.

|

Twite, F., 2016 - Controls of sulphide mineralisation at the Kamoa copper deposit, with an emphasis on structural controls: in School of Geosciences, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa, Unpublished MSc thesis, 288p.

|

Twite, F., Broughton, D., Nex, P., Linnaird. J. and Edwards, D., 2015 - Controls of Sulfide Mineralization at the Kamoa Copper Deposit, with an Emphasis on Structural Controls, SE Democratic Republic of Congo: in SEG 2015: World Class Ore Deposits: Discovery to Recovery Poster 1p.

|

Twite, F., Broughton, D., Nex, P., Linnaird. J., Gilchrist, G. and Edwards, D., 2019 - Lithostratigraphic and structural controls on sulphide mineralisation at the Kamoa copper deposit, Democratic Republic of Congo: in J. of African Earth Sciences v.151, pp. 212-224. doi.org/10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2018.12.016.

|

Twite, F., Nex, P. and Kinnaird. J., 2020 - Strain fringes and strain shadows at Kamoa (DRC), implications for copper mineralisation: in Ore Geology Reviews v.122, doi.org/10.1016/j.oregeorev.2020.103536.

|

|

Porter GeoConsultancy Pty Ltd (PorterGeo) provides access to this database at no charge. It is largely based on scientific papers and reports in the public domain, and was current when the sources consulted were published. While PorterGeo endeavour to ensure the information was accurate at the time of compilation and subsequent updating, PorterGeo, its employees and servants: i). do not warrant, or make any representation regarding the use, or results of the use of the information contained herein as to its correctness, accuracy, currency, or otherwise; and ii). expressly disclaim all liability or responsibility to any person using the information or conclusions contained herein.

|

Top | Search Again | PGC Home | Terms & Conditions

|

|