|

Kvanefjeld Project - Kvanefjeld or Kuannersuit, Sorensen, Zone 3 |

|

|

Greenland |

| Main commodities:

REE U F Zn

|

|

|

|

|

|

Super Porphyry Cu and Au

|

IOCG Deposits - 70 papers

|

All papers now Open Access.

Available as Full Text for direct download or on request. |

|

|

The Kvanefjeld or Kuannersuit Rare Earth Element, uranium and zinc deposits are located on the Erik Aappalaartup Nunaa Peninsula, near the southwestern coast, and 175 km northwest of the southern tip of Greenland. It lies within the municipality of Kujalleq, and is ~8 km northeast of the town of Narsaq, which has a deep water port, and 70 km southwest of Narsarsuaq. It is ~480 km SSE of the Greenland capital, Nuuk. The project includes three deposits, Kuannersuit, Sørensen and Zone 3 (#Location: 60° 58' 30"N, 46° 0' 30"W).

The Kvanefjeld deposit, like the neighbouring Tambreez/Kringlerne within the same host intrusive, was discovered in the mid-1950's and has been the subject of extensive drilling, mapping, mineralogical, geochemical and metallurgical studies since the 1960’s. Active participants have included the Greenland and Danish Geological Surveys, university researchers from the broader European community, and Greenland Minerals and Energy Limited. The Sørensen and Zone 3 resources are more recent discoveries from drilling undertaken since 2008 by the latter company.

After raising funds through a share issue, the Australian ASX listed Greenland Minerals and Energy Limited was established in August 2007 by funding and renaming its precursor, The Gold Company Limited. In May 2007, the latter company had, through a Joint Venture, secured an option to initially acquire 61% and subsequently up to 100% of the Kvanefjeld Project from the UK based Westrip Holdings Limited who had earlier been granted title to the project area. The aim of the new company was to explore for and develop mineral projects in Greenland, particularly focusing on rare earth elements, uranium and sodium fluoride, required for the transition to renewable energy systems and global decarbonisation. The Kvanefjeld Project was Greenland Minerals' flagship property. Drilling commenced later in August of the same year, and continued until 2015 when JORC and NI 43-101 compliant Ore Reserves and Mineral Resources were estimated and a Feasibility Study was released. Some 57 710 m of core were drilled during this period, and test mining from an exploration adit was conducted for metallurgical bulk sampling (IAEA, 2020). The adit is 960 m long and nearly horizontal, its portal on the eastern slope of the Kvanefjeld Plateau, 100 to 150 m below the top, and faces the Narsaq River valley.

In June 2018, the company name was amended to Greenland Minerals Limited, and again in November 2022 to Energy Transition Minerals Limited. Throughout these reorganisations and name changes, the Exploration License covering the Kvanefjeld Project was held by it's Greenland subsidiary, Greenland Minerals and Energy A/S.

In July 2019, the company had applied for an Exploitation licence for rare earth elements. This and subsequent applications have been refused on the basis of Greenland's Inatsisartut Act No. 20 on the prohibition of preliminary investigation, research, exploitation and sale of uranium, which came into force on 2 December 2021. As of late 2023, the company remained in negotiation with the Greenland Government to obtain an Exploitation Licence for Rare Earth Elements. No construction or mining has been undertaken to 2025.

Regional Setting

The Kvanefjeld deposit is hosted within the 1.16 Ga Ilímaussaq Intrusive Complex, that is part of the 1.38 to 1.14 Ga Gardar Province intracratonic volcano-sedimentary rift sequence and related intrusions. The Gardar sequence unconformably overlies the Palaeoproterozoic Ketilidian Mobile Belt that flanks the southern margin of the North Atlantic Craton.

Much of the southern third of Greenland is underlain by the North Atlantic Craton, the eastern extension of the Nain Province of coastal Labrador in Canada. The North Atlantic craton is exposed on the east and west coastal strips of Greenland, separated by the permanent ice cap. It is largely composed of 3.075 to 2.820 Ga Mesoarchaean tonalite-trondhjemite-granodiorite (TTG) gneisses, mafic meta-volcanic and intrusive rocks, anorthosites and, locally, meta-sedimentary units (Henriksen et al., 2000). The latter mostly occur as up to 2 km wide lenses or belts within the gneisses. All of these rocks were metamorphosed to granulite and amphibolite facies grades. In the Nuuk region of West Greenland, the central western sections of the exposed craton, also includes 3.9 to 3.6 Ga Eoarchaean rocks of the Itsaq Gneiss Complex. These represent one of four terranes that were structurally juxtaposed with three Mesoarchaean terranes at ~2.62 Ga (Friend and Nutman, 2005). The blocks/terranes are separated by Archaean faults and shear zones, and are, in most cases, characterised by having associated plutons, that may be proximal to distal, and late- to post-tectonic in character.

To the north, the craton is bounded by the ENE-WSW trending 2.0 to 1.8 Ga Nagssugtoqidian Orogen on the west coastal strip, and the NNW-SSE trending Ammassalik Mobile Belt on the east coast. Both represent Palaeoproterozoic tectonism with a complex deformation history, imposed upon dominantly Neoarchaean 2.8 to 2.7 Ga orthogneisses. Both also include restricted belts/slivers of Archaean and Palaeoproterozoic metasedimentary and metavolcanic rocks that are intercalated within the gneisses.

NOTE: The REE mineralised Sarfartoq Carbonatite Complex (Inferred Resource - 14 Mt @ 1.53% TREO; GEUS, 2018) is exposed at the transition between the Archaean craton and the Nagssugtoqidian Orogen.

To the south, the craton is bounded by the Palaeoproterozoic Ketilidian Mobile Belt (Garde et al., 2002), the rocks of which, unlike those on the northern margin, are largely juvenile. This mobile belt is divided into a Northern, Central and Southern domain (Steenfelt et al., 2016).

• The Southern Domain, is occupied by high-grade, amphibolite to granulite facies gneisses and schists of meta-sedimentary origin, that are subdivided into psammitic- and pelitic zones (Chadwick and Garde, 1996), with a 50 to 80 km wide strip of amphibolite and other rocks of metavolcanic origin on its northern margin. Rocks of this domain, and the southernmost portion of the Central Domain, are intruded by granitic rocks (including rapakivi variants) and associated norites of the Ilua Plutonic Suite (Garde et al., 2002; Steenfelt et al., 2016; Bell et al., 2017).

• The Central Domain, constitutes a 100 to 200 km wide core that is occupied by a continental, calc-alkaline magmatic arc, the Julianehåb Igneous Complex. This complex comprises an initial volumetrically-minor, but areally extensive magmatic event at ~1850 Ma, referred to as the Older Julianehåb Igneous Suite, punctuated by a pause in magmatic activity. This was followed by the Younger Julianehåb Igneous Suite, a major pulse of magmatism between ~1814 and 1795 Ma (Vestergaard et al., 2024). This two part complex comprises a variable suite of plutonic rocks of mafic to felsic compositions, although predominantly granodiorite and granite, and variably metamorphosed/deformed equivalents (Garde et al., 2002; Steenfelt et al., 2016). Spatially restricted, kilometre-scale, remnants of supracrustal rocks also occur within the domain.

• The Northern Domain, comprises reworked Meso- to Neoarchean gneisses, intruded by Palaeoproterozoic granites and unconformably overlain by metasedimentary and metavolcanic rocks (Steenfelt et al., 2016). The best studied part of this poorly known domain (Bagas et al., 2020) consists of Archaean orthogneiss, mafic HT-LP facies metamorphic rocks and ultramafic rocks, unconformably overlain by Palaeoproterozoic meta-volcanic and meta-sedimentary rocks that are intruded by Palaeoproterozoic granites, and mafic and intermediate dykes (Bagas et al., 2020). Early Paleoproterozoic dykes, dated at ~2.4 to 2.0 Ga, also intrude the North Atlantic Craton in the west and their emplacement is interpreted to be associated with crustal extension (Nilsson et al., 2013; Steenfelt et al., 2016).

Sections of the Central, and to a lesser degree, the Northern domains of the Ketilidian Mobile Belt are unconformably overlain by the 1.35 to 1.14 Ga Late Mesoproterozoic Gardar Province, intrusive, extrusive and sedimentary rocks. This sequence is interpreted to have been deposited in a continental/intracratonic rift that has been subsequently uplifted, and comprises sedimentary rocks, mainly sandstones, mantle derived basalts and a variety of volcanic and plutonic igneous rocks of alkaline and peralkaline affinity. It occurs as the ~3500 m thick lavas and sedimentary rocks of the Eriksfjord Formation. The remnants of this rift sequence are of limited extent compared to the Central and Northern domains, and are distributed over an ENE-WSW zone that is 10 to 25 km wide and up to 200 km long. The Eriksfjord Formation is intruded by a large number of dykes, some up to 800 m thick, and several, mostly composite complexes, emplaced into mainly Palaeoproterozoic calc-alkaline Julianehåb granitoids, and subordinately, underlying Archaean gneiss and schist basement. These intrusions span a wide compositional range, from basaltic to trachytic, phonolitic, rhyolitic, lamprophyric and carbonatitic. Anorthositic xenoliths of up to 100 m across are frequently found in some of the mafic and intermediate intrusions, taken to suggest that a large anorthositic complex may be present at depth underlying the whole province (Bridgwater and Harry 1968; Upton et al., 2003). Studies indicate crystallisation of these dykes occurred at ~10 to 12 kbar (30 to 40 km depth) prior to a rapid ascent to upper crustal levels (Halama et al., 2002). The larger dykes may be gabbroic, or composite with gabbroic margins and syenitic to alkali granitic centres. Several of these larger 'central' plutonic complexes intruded to crystallise at shallow crustal levels of ~2 to 5 km, and it is considered likely they many reached the surface to form Gardar Province extrusive equivalents (Emeleus and Upton 1976; Upton et al., 1990). The Gardar Province contains 10 such larger intrusive complexes that range in composition from alkali granite to nepheline syenites and gabbroic dykes (Barnes, 2014). These larger intrusions are often composite, with the most common rock types being quartz syenite, syenite and nepheline syenite, with subordinate alkali granite, gabbro and carbonatite. Most contain layered cumulates and offer evidence for strong in situ fractionational crystallisation (Upton et al., 1996). Some of these complexes are silica-undersaturated and some are wholly oversaturated, possibly a function of variable crustal contamination of the parental magmas (e.g., Marks et al., 2003, 2004). The Ilímaussaq Intrusive Complex is one of these large Gardar Province intrusions and possibly one of the youngest (Bailey et al., 2001). Unlike most other Gardar intrusions, the Ilímaussaq Complex contains both quartz-bearing and nepheline-bearing phases, although the latter predominate (Mark and Markl, 2015).

The Ilímaussaq Intrusive Complex has been variously dated at 1143 ±21 Ma (Sørensen, 2001, recalculated from Blaxland et al., 1976), 1130 ±50 Ma (Paslick et al., 1993), 1160 ±5 Ma (U-Pb, Markl, 2000), 1160.7 ±3.4 Ma and 1161.8 ±3.4 Ma (Rb-Sr, Waight, quoted by Sørensen 2001).

Ilímaussaq Intrusive Complex

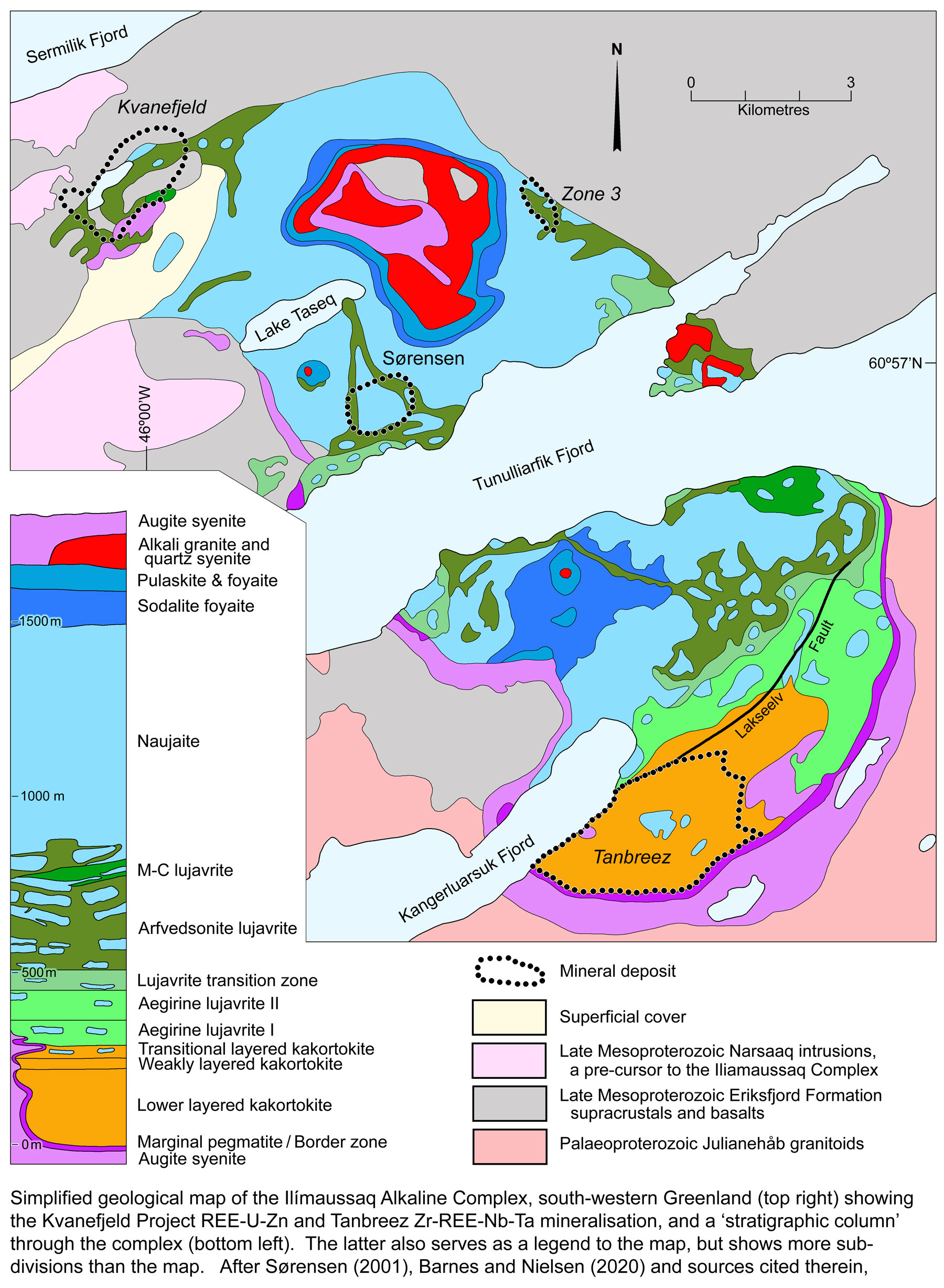

The NW-SE elongated Ilímaussaq Intrusive Complex (see image below), which is generally flat lying, to shallowly dipping, covers an area of ~17 x 8 km. It extends from the Narsaq Peninsula in the NW, southward across two other peninsulas, to straddle the Tunulliarfik and upper reaches of the Kangerluarssuk fjords. The main layered complex is estimated to have a vertical thickness of ~1700 m and to have been emplaced at a depth of 3 to 4 km below surface (Sørensen, 2001). It is composed of distinct layers that are attributed to successive pulses of evolving magma.

Three intrusive phases have been recognised in the development of the Ilímaussaq complex.

The first phase is composed of augite syenite, which has a xenomorphic texture, with grain sizes varying from 2 to 20 mm. It is only preserved as a partial marginal shell and in the roof of the complex, growing inward and downward from the chamber margin, forming a partial 'ring dyke' around the southern half of the complex. The principal minerals of this phase are strongly exsolved perthitic alkali feldspar, olivine, clinopyroxene and Fe-Ti oxides.

The succeeding second phase consists of alkali granite and quartz syenite which are similarly inward growing, restricted to the roof of the complex, but are also preserved as blocks that have been detached, and engulfed by the underlying younger melts of the third intrusive phase.

The third intrusive phase occupies the bulk of the complex, and is characterised by the presence of agpaitic nepheline syenites. An agpaitic rock is a peralkaline igneous lithology, typically nepheline syenite or phonolite. Characteristics include complex silicates containing zirconium, titanium, sodium, calcium, the rare-earth elements and fluorine. Agpaites are unusually rich in rare and obscure minerals such as eudialyte [Na15Ca6Fe3Zr3Si(Si25O73)(O,OH,H2O)3(Cl,OH)2, where REO may substitute for Ca], wöhlerite, loparite, astrophyllite, lorenzenite, catapleiite, lamprophyllite and villiaumite [NaF]. These minerals all have high sodic contents. Sodalite [Na4(Si3Al3)O12Cl] is typically present, but is not diagnostic.

The third phase is sub-divided into three series, the Floor, Intermediate and Roof Series.

The Roof Series crystallised from the top downwards, progressing from non-agpaitic pulaskite at the top, through pulaskite and foyaite and sodalite foyaite, to end with distinctly agpaitic naujaite. Pulaskite and the pulaskite and foyaite transition comprises a massive and medium to coarse grained rock, with platy alkali feldspar and nepheline, hedenbergite, fayalite, aegerine-augite to aegerine and katophorite, minor titanomagnetite, apatite, aenigmatite, biotite, fluorite and eudialyte. The sodalite foyaite has a coarse platy texture and is essentially composed of alkali feldspar, nepheline, sodalite, aegirine-augite to aegirine, katophorite and arfvedsonite, with minor fayalite, hedenbergite, apatite, aenigmatite, titano-magnetite, eudialyte, rinkite, fluorite and biotite. Naujaite is a poikalitic to pegmatitic cumulate rock composed of large (up to 5 mm) euhedral sodalite crystals that floated towards the top of the magma chamber. Later crystallising phases are mainly composed of nepheline, alkali-feldspar, aegirine, arfvedsonite, and eudialyte, which result in the predominantly poikilitic texture. Individual feldspars can be up to 25 cm, and both aegirine and arfvedsonite can form crystals up to 30 cm long. The amount of eudialyte in naujaite is not consistent, and it may be completely absent. Rinkite [(Ca3Ce)Na(NaCa)Ti(Si2O7)2(OF)F2] is a common accessory mineral.

The Floor Series cooled from the bottom upwards, and is composed of a layered and laminated sequence of kakortokite. Kakortokite is an agpaitic nepheline syenite with pronounced cumulate textures and igneous layering with a repetition of layers enriched in alkali feldspar, nepheline, aegirine, eudialyte and arfvedsonite.

The kakortokite of the Floor Series passes gradually upwards, through transitional facies into the lujavrites that characterise the Intermediate Series which has transitional margins above and below. Lujavrites are agpaitic to hyper-agpaitic nepheline syenites that are generally fine-grained, laminated and occasionally layered, although locally, they may be massive and coarse grained. Overall the lujavrites are fine grained (<0.6 mm), although component sodalite grains may be up to 2 mm and mafic minerals up to 1 mm. Deposition of the Intermediate Series represents the final stages of development of the Ilímaussaq Intrusive Complex, representing the emplacement of residual melts remaining after the contemporaneous crystallisation of the Roof and Floor series. As such, the lujavrites are the most highly evolved rocks of the Ilímaussaq complex and are characterised by elevated contents of elements such as Li, Be, Zr, REE, Nb, Th and U (Sørensen et al., 2006; Sørensen 2003). However, Sørensen et al. (2006) report field observations and geochemical data that they interpret to suggest the floor cumulates and the main mass of lujavrites constituted a separate intrusive phase which was emplaced into the already consolidated Roof Series rocks. Note that the roof of the complex includes the thick Third Phase Roof Series Naujaites, and the earlier crystallised Second Phase alkali acid rocks and First Phase augite syenite.

Three major groupings of lujavrites have been distinguished:

i). green lujavrite, in which aegerine is the dominant mafic mineral;

ii). black lujavrite, which is fine-grained, often laminated, with arfvedsonite as the major mafic mineral;

iii). medium to coarse grained lujavrite, M-C lujavrite, again with dominant arfvedsonite, but generally showing foyaitic (i.e., platy trachytic) textures.

A fourth, less extensive grouping, naujakasite lujavrite, is associated with the hyper-agpaitic stage of the complex, characterised by exceptionally high Na/K ratios (Khomyakov, et al., 2001). In these rocks, naujakasite

[Na6Fe2+Al4Si8O26] generally occurs at the expense of nepheline, and locally comprises up to 75 vol.% of the lujavrite. While common at Kvanefjeld, it only forms minor horizons, rarely thicker than 50 m, and usually only 5 to 10 m wide. Naujakasite lujavrite occurs in the uppermost sections of sheets of arfvedsonite lujavrite, often in contact with overlying naujaite xenoliths and rafts of augite syenite and volcanic rocks that were detached from the roof (Khomyakov, et al., 2001). The water-soluble mineral villiaumite [NaF] is abundant in most of the lujavrites but has been leached in some near-surface. Lujavrites, particularly naujakasite lujavrite, are very strongly enriched in incompatible elements such as rare earth elements, lithium, beryllium and uranium.

The 'stratigraphy' of the Ilímaussaq Intrusive Complex, as illustrated on the image above, may be described as follows, from the base upward:

• Floor Series, which is ~300 m thick and is principally composed of banded kakortokite, the base of which had not been intersected until 2007. Drilling in that year intersected a black to grey, fine grained to porphyritic rock, the matrix of which was peppered with sodalite. This rock, which was nicknamed 'Black Madonna', contains 5 to 10 vol.% subhedral to euhedral, poikilitic biotite that is 1 to 2 mm in diameter, with associated aggregates of aenigmatite [Na2Fe2+5TiSi6O2], biotite and arfvedsonite in a groundmass of feldspar, nepheline and sodalite [Na4(Si3Al3)O12Cl]. Geochemically, it has the composition of a tephri‐phonolite - a highly alkaline rock containing 60 to 90% felspathoids. For more details see the Ilímaussaq Intrusive Complex section of the Tanbreez record.

The lower-most section of the kakortokite is composed of centimetre scale layers accentuated by varying amounts of mafic minerals, feldspar and eudialyte. The banding it exhibits is affected by 'trough structures' and 'cross-laminations'. These are overlain by 29 x units, each of which is ~10 m thick and composed of three layers (after Bohse et al. 1971), i). a lower, black layer that is rich in arfvedsonite; ii). a middle, often thinner, red layer rich in eudialyte; and iii). an upper, much thicker white layer that is rich in nepheline and alkali-feldspar. The black, red and white layers pass gradually into each other, whilst, in contrast, the white and overlying black layer of the next unit have a sharp contact. Each of the layers has a consistent thickness throughout the unit, although not all of the 29 units contain all three layers. Bailey et al. (2001) calculated that the bulk kakortokite contains 12.7% black, 11.5% red and 75.8% white layers. The individual units are labelled, from -11 to +27, based on their position with respect to a specific marker unit zero.

It has been postulated that the lower-most sodalite-bearing level of, and below the kakortokite in the Floor Series, may be contemporaneous with the lower part of the naujaite in the Roof Series, whilst the uppermost section of the Roof Series likely crystallised simultaneously with the unexposed lower part of the Floor Series and the underlying tephri‐phonolite (Sørensen and Larsen 1987).

The kakortokite of the floor series is laterally rimmed by an up to 100 m wide contact zone which is termed the marginal pegmatite (Bohse et al., 1971, Andersen et al., 1988, Sørensen, 2006). This zone passes gradually inward into the main mass of layered kakortokite and consists of a matrix of agpaitic nepheline syenite that is penetrated by short pegmatite veins.

The layered kakortokite of the Floor Series grades upwards, via a weakly layered facies, into a thin unit of transitional layered kakortokite, which, in turn, passes gradually into the Intermediate Series of lujavrites. This transitional unit is agpaitic, meso- to fine-grained, laminated and occasionally layered (Sørensen and Larsen 1987).

• Intermediate Series, which is ~450 m thick. As detailed above, there is a gradual and concordant contact between the Floor Series kakortokite and overlying aegirine lujavrite. Bohse and Andersen (1981) distinguish a lower aegirine lujavrite I zone, characterised by weakly developed macro-rhythmic layering (Bailey 1995). This zone has a gradational upper contact with the aegirine lujavrite II zone. This second zone, and the succeeding lujavrite transition zone, arfvedsonite lujavrite and the uppermost medium- to coarse-grained lujavrite (M-C lujavrite), are defined by progressively more stratified and more evolved lujavrites at higher levels within the Intermediate Series. The M-C lujavrite occurs as intrusive sheets, with grain size and texture that approaches a pegmatite. The first three of these are ~100 m thick, whilst the arfvedsonite lujavrite zone is ~200 m. These lujavrite phases engulf blocks of naujite characteristic of the Roof Series that increase upward, both in size and frequency.

• Roof Series, which is principally composed of naujaite, and occupies the lower ~700 m of this series. These pass upwards into ~120 m of sodalite and foyalite and then to <100 m of pulaskite and foyaite, as described above. These are overlain by the alkali acid rocks and augite syenites of the second and first magmatic phases respectively, also described above.

Geology and Mineralisation

The Kvanefjeld REE-U-Zn deposit is hosted within the uppermost steenstrupine-bearing lujavrites of the Intermediate Series of the Ilímaussaq Intrusive Complex, and within overlying fenitised roof rocks to the complex that are also rich in steenstrupine. In this hyper-agpaitic stage of the intrusion, steenstrupine occurs instead of eudialyte, and the intrusive is characterised by naujakasite, steenstrupine, ussingite, vitusite and other related minerals.

The lujavrite series within the northwestern half of the Ilímaussaq Complex is generally fine-grained and laminated, although there are locally some medium to coarse-grained pegmatoidal varieties. The black arfvedsonite lujavrite facies of the complex is the principal host to the REE, uranium, and zinc multi-element mineralisation within the Kvanefjeld deposits. Mineralisation is predominantly orthomagmatic, with metal enrichment a function of differentiation of the lujavrite magma. Economic REE and uranium grades are associated with distinct ore minerals, the dominant of which for both REE and uranium is steenstrupine [Na14Mn2+2Fe3+2Ce6Zr(Si6O18)2(PO4)6(PO3OH)(OH)2•2H2O]. The preceding is the generalised formula from Mindat.org, which includes U, Th and other REEs in the mineral lattice, and, as such, may alternatively be expressed as

[Na14Mn2+2Fe3+2(REE)6(U,Th,Zr)(Si6O18)2(PO4)6(PO3OH)(OH)2•2H2O],

or [Na6.7HxCa(REE)6(Th,U)0.5(Mn1.6Fe1.8Zr0.3Ti0.1,Al0.2)(P4.3Si1.7)O24)(F,OH).nH2O], after Krebs and Furfaro (2020).

Zoning of steenstrupine crystals/grains has been described by a number of authors, and this zonation has been shown to correlate with their content of U and Th (Khomyakov and Sørensen, 2001 and references cited therein). Most steenstrupine crystals are amorphous (metamict), at least in part, whilst others are crystalline (anisotropic) throughout, and others again, have amorphous cores and thin outer crystalline shells. Where fractured, those fractures are lined by anisotropic tongues that penetrate into the amorphous interior of the crystals/grains. The amorphous steenstrupine grains have higher U and Th than than those that are crystalline (anisotropic), whilst amorphous cores have higher contents of these same elements than their outer crystalline rims. Conversely, the anisotropic sections have higher ZrO2, MnO, Na2O and

P2O5 represented by an increase from centre to rim. This has been interpreted to suggest crystallisation, in and from, a medium in which decreasing amounts of U and Th were available during the final stages of growth of the crystals. Khomyakov and Sørensen (2001) also suggest that the observation that the marginal zones of the steenstrupine crystals are thin and perfectly parallel and enriched in Na is most easily understood as a growth phenomenon and is less likely to be the result of leaching and recrystallisation.

The U and Th contents of steenstrupine have been variously shown to be in the ranges 0.1 to 1.4 wt.% U and 0.2 to 7.4 wt.% Th (Hansen, 1977). Makovicky et al. (1980) found, via fission track studies, that the altered centres of steenstrupine crystals carried up to 1 wt.% U3O8, whilst the light-coloured parts of the crystals had 0.2 to 0.5 wt.%. The same authors applied microprobe analyses to show variations in the composition of the mineral from 0.27 to 5.69 wt.% Th, with some zoned crystals carrying 3.11 to 3.74 wt.% Th in the centres, declining to 1.03 to 2.05 wt.% Th on the rims.

Khomyakov and Sørensen (2001) determined, via microprobe analysis, the ΣRe2O3 content of 6 samples of steenstrupine from the Ilímaussaq Intrusive to range from 27.71 to 34.58 wt.%. Individual rare earth oxides from the same samples were in the range

8.78 to 14.22 wt.% La2O3;

13.76 to 16.49 wt.% Ce2O3;

1.04 to 2.39 wt.% Pr2O3;

2.78 to 4.22 wt.% Nd2O3 and

0.15 to 0.31 wt.% Sm2O3; while there was also

up to 2.33 wt.% ZrO2;

0.10 to 1.56 wt.% Y2O3 and

0.10 to 0.67 wt.% Nb2O5.

However, unlike U and Th, the content of the rare earth oxides analysed, namely,

La2O3,

Ce2O3,

Pr2O3,

Nd2O3 and

Sm2O3, are comparable in the centre and rim of individual steenstrupine crystals. The exception is Y2O3, which declines from centre to rim.

The 2015 Greenland Minerals Feasibility Study indicates a similar trend and magnitude, noting that the steenstrupine at Kvanefjeld commonly contains between 0.2 and 1% U3O8, and >15% total rare earth oxide.

As the steenstrupine formula indicates, it is a complex sodic phospho-silicate mineral. The phosphorous within the mineral structure makes steenstrupine amenable to concentration by conventional flotation techniques. It's grain size commonly ranges from 75 to >500 µm. As such, steenstrupine is a constituent igneous mineral distributed through the lujavrite intrusive, a variety of nepheline syenite.

Other minerals that are important hosts to REEs include the phosphate minerals vitusite [Na3(Ce,La,Nd)(PO4)2] and, to a lesser extent, britholite [(REE,Ca)5{(Si,P)O4}3X - where X = F-, (OH)-, Cl-], lovozerite [H4Na2Ca(Zr,Ti){Si6O18}] group silicate minerals and rarely monazite. In addition, uranium is also hosted in zirconium silicate minerals of the lovozerite group, where a portion of the zirconium is substituted by several hundred ppm each of uranium, yttrium, REEs and tin. Zinc is hosted in the sulphide mineral sphalerite, which is the dominant sulphide, disseminated throughout the deposits.

The upper, higher grade i.e., >300 ppm U3O8, sections of the Kvanefjeld deposit dominantly contain REEs and uranium within phosphate bearing minerals, particularly steenstrupine, with the zirconium silicates being of secondary importance. However, at greater depth, the zirconium silicates become increasingly important hosts to uranium. The mine schedule is focussed on first extracting the upper level of the Kvanefjeld deposit.

The resource model generally follows the upper and lower lujavrite contact. To the north, at the Kvanefjord deposit, zones of black lujavrite >200 m thick outcrop at surface, whilst to the south at Sørensen and Zone 3, the lujavrite forms a series of thinner lenses. As detailed above, the highest REE, uranium and zinc grades occur together in the upper parts of the resource model. Grades begin to decrease below 200 m from ground surface. The proposed stripping ratio is estimated to average 1:1 over the first 37 years of mining.

In plan, the substantial Kvanefjeld multi-element (REE-U-Zn) resource and two satellites, Sørensen and Zone 3, have been delineated in the rhomboid-shaped northern half of the Ilímaussaq Complex (see image above). This rhomboid shape has an east-west, 10 km long diagonal, by 7 km north-south. Extensive outcrops of lujavrite mark the Kvanefjeld deposit, whilst, in contrast, the Sørensen and Zone 3 deposits occur as sills within the lujavrites at a high level within the Complex.

The Kvanefjeld deposit lies along the north-western side of the rhomboid, internal to, and bounded by the intrusive margin, close to it's western extremity. Zone 3 is a near mirror image along the northeastern margin, towards the eastern end of the intrusive, whilst Sørensen is within the intrusive, a few hundred metres north of it's southern extremity. Geological evidence and reconnaissance drilling suggest that Sørensen and Zone 3 are exposures of a mineralised system that extends over several kilometres from Kvanefjeld, and the three may be interconnected at depth. The drilled area of the Kvanefjeld deposit is ~2 x 0.9 km, internal to the Ilímaussaq Intrusive Complex and elongated parallel to northwestern margin.

Kvanefjeld is a massive, bulk, low grade mineral resources, mostly outcropping. The ores are conducive to simple, cost-competitive processing, and can be exported year-round via a deep water shipping port 8 km SW of the proposed mine. Proposed infrastructure comprises an open pit mine, a concentrator and refinery. The concentrator is expected to produce a critical mixed rare earth oxide concentrate containing 20 to 25% rare earth oxide. Critical rare

earths include neodymium, praseodymium, europium, dysprosium, terbium and yttrium. These concentrates are planned to be upgraded to high-purity intermediate rare earth products in the refinery. The concentrator and refinery are expected to also produce various by-products for sale, including uranium oxide, lanthanum and cerium products and zinc concentrate. Rare earth products are forecast to generate over 80% of the project’s revenue, with by-products contributing the balance. Uranium is estimated to account for 5% of mine revenue. Technical studies have indicated that the unique rare earth and uranium bearing minerals, as discussed above, can be concentrated to <10% of the original ore mass with froth flotation. The ore minerals are also non-refractory and can be effectively treated using an atmospheric sulphuric acid leach, with no requirement for complex mineral 'cracking'.

Reserves and Resources

JORC and NI 43-101 compliant Ore Reserves and Mineral Resources, as published by Greenland Minerals and Energy Limited in 2015, and repeated in the December 2023 Annual Report of Energy Transition Minerals, are as follows:

Mineral Resources

At a 150 ppm U3O8 cut-off:

Kvanefjeld - estimated February 2015

Measured Resource - 143 Mt @ 1.21% TREO+, 303 ppm U3O8, 1.07% LREO, 432 ppm HREO, 1.11% REO, 978 ppm Y2O3, 0.237% Zn,

Indicated Resource - 308 Mt @ 1.11% TREO+, 253 ppm U3O8, 0.98% LREO, 411 ppm HREO, 1.02% REO, 899 ppm Y2O3, 0.229% Zn,

Inferred Resource - 222 Mt @ 1.00% TREO+, 205 ppm U3O8, 0.88% LREO, 365 ppm HREO, 0.92% REO, 793 ppm Y2O3, 0.218% Zn,

TOTAL Resource - 673 Mt @ 1.09% TREO+, 248 ppm U3O8, 0.96% LREO, 400 ppm HREO, 1.00% REO, 881 ppm Y2O3, 0.227% Zn.

Sørensen - estimated March 2012

Inferred Resource - 242 Mt @ 1.10% TREO+, 304 ppm U3O8, 0.97% LREO, 398 ppm HREO, 1.01% REO, 895 ppm Y2O3, 0.260% Zn,

Zone 3 - estimated May 2012

Inferred Resource - 95 Mt @ 1.16% TREO+, 300 ppm U3O8, 1.02% LREO, 396 ppm HREO, 1.06% REO, 971 ppm Y2O3, 0.277% Zn.

TOTAL Measured + Indicated + Inferred Mineral Resource - for all three deposits

- 1010 Mt @ 1.10% TREO+, 266 ppm U3O8, 0.97% LREO, 399 ppm HREO, 1.01% REO, 893 ppm Y2O3, 0.240% Zn.

NOTE: TREO+ = Total Rare Earths in the Lanthanide Series + Yttrium. The Lanthanide Series are La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Pm, Sm, Eu, Gd, Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm, Yb and Lu; LREE = La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Pm, Sm, Eu and Sc; HREE = Gd, Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm, Yb, Lu and Y; REO = LREO + HREO.

Ore Reserves - estimated February 2015

Proved Ore Reserve - 43 Mt @ 1.47% TREO+, 352 ppm U3O8, 1.30% LREO, 500 ppm HREO, 1113 ppm Y2O3, 0.270% Zn.

Probable Ore Reserve - 64 Mt @ 1.40% TREO+, 368 ppm U3O8, 1.25% LREO, 490 ppm HREO, 1122 ppm Y2O3, 0.250% Zn.

TOTAL Ore Reserve - 108 Mt @ 1.43% TREO+, 362 ppm U3O8, 1.27% LREO, 495 ppm HREO, 1118 ppm Y2O3, 0.260% Zn.

At a higher 350 ppm U3O8 cut-off, TOTAL Mineral Resources become:

Kvanefjeld - 122 Mt @ 1.40% TREO+, 398 ppm U3O8, 1.23% LREO, 506 ppm HREO, 1.28% REO, 1195 ppm Y2O3, 0.257% Zn.

Sørensen - 92 Mt @ 1.24% TREO+, 422 ppm U3O8, 1.10% LREO, 422 ppm HREO, 1.14% REO, 1004 ppm Y2O3, 0.308% Zn.

Zone 3 - 24 Mt @ 1.30% TREO+, 392 ppm U3O8, 1.14% LREO, 471 ppm HREO, 1.19% REO, 1184 ppm Y2O3, 0.304% Zn.

TOTAL tonnage of resource - 238 Mt.

High grade upper sections of each include (Greenland Minerals and Energy Limited Feasibility Study, 2015):

Kvanefjeld - 54 Mt @ 1.40% TREO+, 403 ppm U3O8, 0.24% Zn.

Sørensen - 119 Mt @ 1.20% TREO+, 400 ppm U3O8, 0.30% Zn.

Zone 3 - 47 Mt @ 1.20% TREO+, 358 ppm U3O8, 0.30% Zn.

References are yet to be added

The most recent source geological information used to prepare this decription was dated: 2017.

This description is a summary from published sources, the chief of which are listed below.

© Copyright Porter GeoConsultancy Pty Ltd. Unauthorised copying, reproduction, storage or dissemination prohibited.

Kvanefjeld

|

|

|

|

Porter GeoConsultancy Pty Ltd (PorterGeo) provides access to this database at no charge. It is largely based on scientific papers and reports in the public domain, and was current when the sources consulted were published. While PorterGeo endeavour to ensure the information was accurate at the time of compilation and subsequent updating, PorterGeo, its employees and servants: i). do not warrant, or make any representation regarding the use, or results of the use of the information contained herein as to its correctness, accuracy, currency, or otherwise; and ii). expressly disclaim all liability or responsibility to any person using the information or conclusions contained herein.

|

Top | Search Again | PGC Home | Terms & Conditions

|

|