|

Tanbreez Project - Kringlerne (Killavaat Alannguat) |

|

|

Greenland |

| Main commodities:

Zr REE Nb Ta

|

|

|

|

|

|

Super Porphyry Cu and Au

|

IOCG Deposits - 70 papers

|

All papers now Open Access.

Available as Full Text for direct download or on request. |

|

|

The highly fractionated, ortho‐magmatic, Tanbreez or Kringlerne (Killavaat Alannguat) zirconium, niobium, tantalum, rare earth element deposit is hosted within the southeastern half of the Late Mesoproterozoic Ilímaussaq Intrusive Complex, near the southwestern coast of Greenland. It falls within the municipality of Kujalleqq, 12 km east-southeast of Narsaq, ~175 km northwest of the southern tip of Greenland, ~485 km south-southeast of the Greenland capital, Nuuk and 15 km southeast of the Kvanefjeld REE-U-Zn deposit.

(#Location: 60° 52' 5"N, 45° 50' 16"W).

The original Kringlerne deposit, like the neighbouring Kvanefjeld in the same host intrusive, was discovered in the mid-1950's. The knowledge base of the deposit area dates as far back as the1880s and includes extensive, mapping, mineralogical, geochemical and metallurgical studies, as well as more recent drilling carried out by the former and by the current title holder. Active participants have included the Greenland and Danish Geological Surveys, and university researchers from the broader European community. In 2001, Rimbal Pty Ltd, the Australian private company that owns the Greenland registered holding company, Tanbreez Mining Greenland A/S, was granted an exploration license over the Kringlerne deposit, later to be renamed Tanbreez, an anagram based on the major commodities it carries, namely the elements Ta‐Nb‐REE‐Zr. The subsequent years were spent understanding and testing the deposit. This involved 414 drill holes and more than 366 000 assays. Substantial bulk testing, totaling ~709 tonnes, was also undertaken. Testing has progressed to estimating a JORC (2012) compliant Inferred Mineral Resource. An Exploitation License was granted to Rimbal Pty Ltd by the Greenland Government in 2020, permitting mining of the deposit. The project has also won preliminary environmental approval. On 10 June 2024, the US NASDAQ listed Critical Metals Corp. signed a binding heads of agreement to acquire a controlling interest in the Tanbreez Greenland Rare Earth mine from Rimbal Pty Ltd. In September 2024, Critical Metals commenced a drilling program to begin to confirm and upgrade the existing Mineral Resource from Inferred to Indicated, and to enhance feasibility analysis.

Regional Setting

See the Regional Setting description for the Kvanefjeld Project record.

Ilímaussaq Intrusive Complex

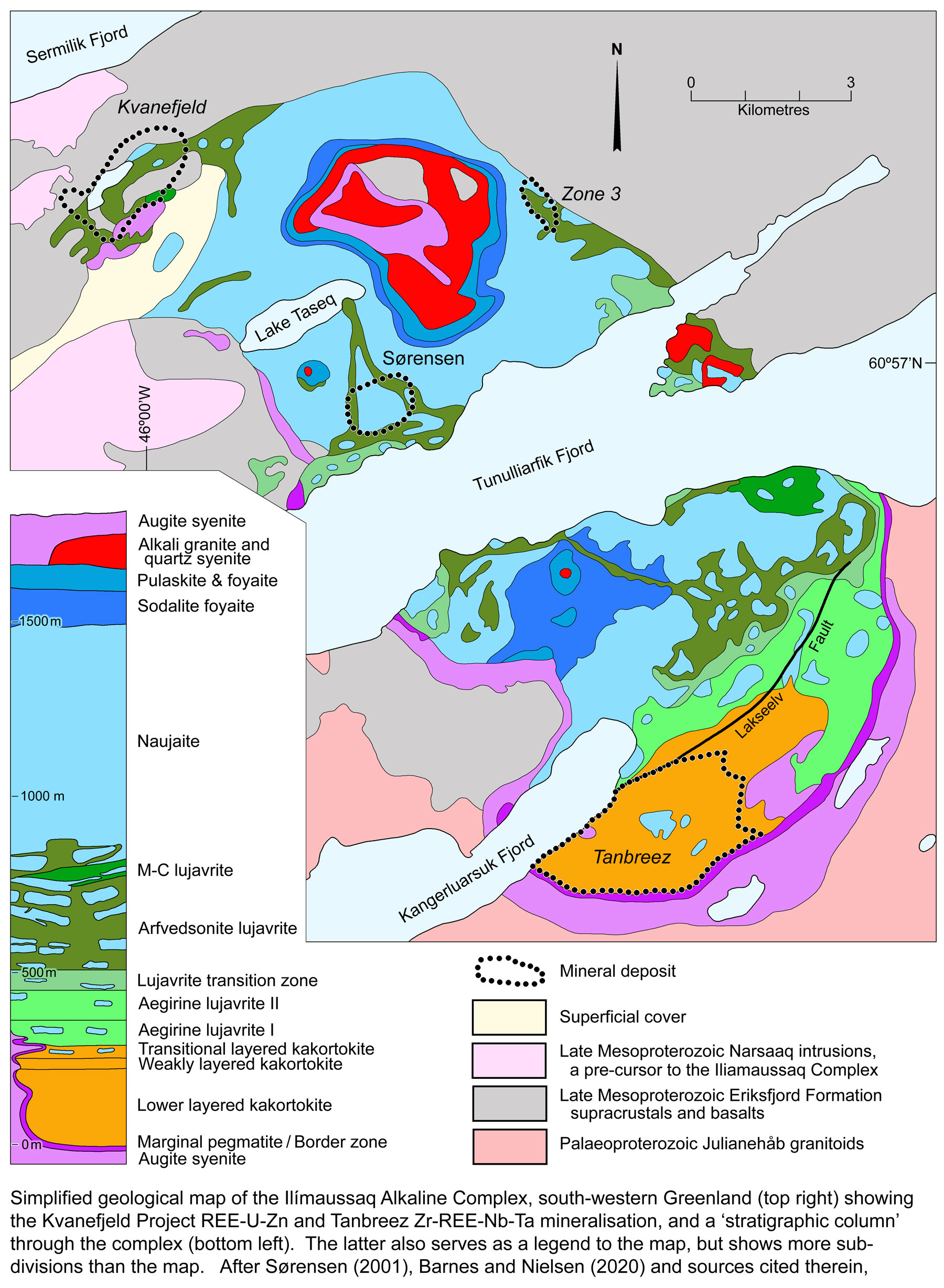

The NW-SE elongated Ilímaussaq Intrusive Complex (see image below), which is generally flat lying, to shallowly dipping, covers an area of ~17 x 8 km. The main layered complex is estimated to have a vertical thickness of ~1700 m and to have been emplaced at a depth of 3 to 4 km below surface (Sørensen, 2001). It is composed of distinct layers that are attributed to successive pulses of evolving magma.

Three intrusive phases have been recognised in the development of the Ilímaussaq complex.

The first phase is composed of augite syenite, which is only preserved as a partial marginal shell and in the roof of the complex, growing inward and downward from the chamber margin, forming a partial 'ring dyke' around the southern half of the complex.

The succeeding second phase consists of alkali granite and quartz syenite which are similarly inward growing, restricted to the roof of the complex, but are also preserved as blocks that have been detached, and engulfed by the underlying younger melts of the third intrusive phase.

The third intrusive phase occupies the bulk of the complex, and is characterised by agpaitic nepheline syenites. This third phase is divided into an ~300 m thick Floor Series of banded kakortokite, an ~450 m thick Intermediate Series of lujavrite and a ~820 m thick Roof Series, largely composed of naujaite.

For a detailed description of the complex, see the Ilímaussaq Intrusive Complex description for the Kvanefjeld Project record. However, as the Kvanefjeld Project REE, U, F and Zn deposits are hosted by the lujavrites of the Intermediate Series in the northwestern half of the intrusion, that description concentrates on the upper sections of the complex.

In contrast, the Tanbreez Zr, Nb, Ta, REE and Hf deposit is hosted within the kakortokites of the Floor Series in the south-eastern half of the intrusive complex. The following builds upon the Kvanefjeld record to provide detail on the lower sections of the complex.

Whilst the upper boundary between the kakortokite and overlying lujavrite facies at the Floor to Intermediate Series interface is gradual and well defined, as described in the linked description above, the base of the kakortokites had not been observed until 2007. In that year, drilling was undertaken by Tanbreez Mining in the coastal zone adjacent to Kangerdluarsuk Fjord, passing through the base of the then known kakortokite, near the southern margin of the Ilímaussaq intrusion. This drilling intersected a black to grey, fine grained to porphyritic rock, the matrix of which was peppered with sodalite. This rock, which was nicknamed 'Black Madonna', contains 5 to 10 vol.% subhedral to euhedral, poikilitic biotite that is 1 to 2 mm in diameter, with associated aggregates of aenigmatite [Na2Fe2+5TiSi6O2], biotite and arfvedsonite in a groundmass of feldspar, nepheline and sodalite [Na4(Si3Al3)O12Cl]. Geochemically, it has the composition of a tephri‐phonolite - a highly alkaline rock containing 60 to 90% felspathoids. By 2014, it had been intersected in 8 drill holes, with the longest recovered interval being 220 m. Sufficient drilling had been undertaken after this program to draw a reasonably good correlation of the kakortokite to massive 'Black Madonna' contact between these drill holes. From this, it appears that the top of the Black Madonna is dipping towards the NW, parallel to the layering of the overlying kakortokite. A further drill hole, 1.5 km further to the east in 2010, has apparently corroborated this interpretation. Schonwandt et al. (2014) suggest the Black Madonna could underlie the entire kakortokite sequence. Its upper contact with the Lower Layered Kakortokite is well defined although not sharp. The layered kakortokite above the contact zone encloses 5 to 10 cm long, rounded xenolthic inclusions of Black Madonna, which may persist, with diminishing frequency, for up to 50 m or more above the contact (Schonwandt et al., 2014).

As detailed previously, the top, base and lateral margins of the Ilímaussaq Intrusive Complex are occupied by an outer, variably developed, rim or 'ring dyke' of early cooling, first phase, non-agpaitic augite syenite that varies from being locally absent, to as much as a kilometres in width. The lateral margin of the kakortokite within this outer rim, and where absent, the intrusion wall, is occupied by a transitional rind. This rind comprises a massive, agpaitic nepheline syenite that is composed of the same minerals as the layered kakortokite sequence. It forms a transitional border zone, also referred to as the marginal pegmatite. This 'border zone/marginal pegmatite' is ~150 m wide at sea level on the southern shoreline of the Kangerluarsuk Fjord, but diminishes to ~50 m at an elevation of ~450 m as the contact steepens up-dip. It is a complex mixture of different eudialyte‐bearing rock types, including pegmatite, made up of eudialyte-bearing nepheline syenite, which has a texture that varies from medium- to coarse‐grained and is largely massive. The inner margin abutting the banded kakortokite, exhibits a gradation over ~5 to 10 m where the layering becomes more subtle outwards, and morphs into a massive agpaitic rock. In contrast, the outer boundary with the augite syenite, is subvertical, sharp and lacks a chilled margin. Between these two end members, the 'border zone/marginal pegmatite' is a complex intergrowth of texturally different kakortokite like rocks. It is cut by eudialyte poor pegmatite veins, predominantly composed of feldspar, nepheline, sodalite, arfvedsonite and aegirine. The proportion of pegmatite increases towards the augite syenite, whilst the veins largely parallel the contact with the latter. In the outer 10 m, a subvertical swarm of pegmatite veins occur, locally associated with hydrothermal alteration. The pegmatite is un-mineralised, and the youngest member of the 'border zone' and consequently, dilutes mineralisation grades.

Geology and Mineralisation

The Tanbreez Zr, Nb, Ta, REE and Hf deposit is hosted within the kakortokites of the Floor Series in the south-eastern half of the Ilímaussaq Intrusive Complex, in contrast to the neighbouring Kvanefjeld Project REE, U, F and Zn deposits hosted by the overlying lujavrites of the Intermediate Series in the northwestern half of the same intrusion.

In the southeastern half of the Ilímaussaq Intrusive Complex, the kakortokite and immediately overlying lujavrite facies, constitute the lower sequence of the 'stratified' intrusion, and together are exposed over a thickness of ~800 to 1000 m, of which the kakortokites account for ~285 m. Overall, all planar magmatic elements/banding within this part of the intrusion are locally parallel, defining a combined structure that has a 'saucer shape', with steep, to vertical, dips on the periphery. These steep peripheral dips rapidly rotate into a general 10 to 15° inward below the main intrusive body of the kakortokite, although some steeper dips are found just north of the Lakseelv Fault. This saucer-shape would appear to represent the base and lateral margins of the intrusion, with local rotation across later faulting. In contrast, across the Tunulliarfik Fjord, the northwestern half of the intrusion, which hosts the Kvanefjeld deposits, represent its roof.

In the main southeastern half of the intrusion, the kakortokite covers an area of ~5 x 2.5 km on the south side of the Kangerdluarsuk Fjord and is exposed from sea level up to ~400 m elevation. Within this area it comprises 95% kakortokite with ~5% other related rocks, mostly syenite dykes and sills. Over this interval, it has been vertically subdivided into three parts, from bottom to top:

• Lower Layered Kakortokite, which is ~209 m thick, with layering that is described as spectacular (Schonwandt et al., 2014), composed of sub-horizontal black, red and white bands, reflecting the preponderance of specific mineral assemblages. The black layers contain >45% arfvedsonite, with lesser eudialyte, alkali feldspar and nepheline. The red layers are dominated by >25% eudialyte, with lesser arfvedsonite, alkali feldspar and nepheline, whereas the white layers are primarily composed of alkali‐feldspar and nepheline with lesser arfvedsonite and eudialyte. Sodalite is locally significant. The Zr and REE rich mineral eudialyte [Na15(Ca,REE)6Fe3(Zr,Nb)3Si(Si25O73)(O,OH,H2O)3(Cl,OH)2] makes up slightly <10% of the black and white layers, but ~30 to 40% of the red layers.

Traditionally, in the literature, the triplet of coloured layers together have been defined as forming a unit. Some 29 such units have been mapped in the exposed sections of the Lower Layered Kakortokite, labelled -11 to -1 and +1 to +17, below and above unit 0, respectively. The uppermost with extensive exposure is unit +16, while unit +17 is restricted to small erosional remnants (Andersen et al., 1988; Bohse et al., 1971). Unit 0 is the thickest and best developed of the 29. Whilst the layering within these units is evident from a distance, on close inspection and in drill core, exact contacts are gradational and difficult to pinpoint. This is particularly the case between the black, red and white layers, although, in contrast, the white and overlying black layer of the next unit usually have a sharper contact. Variations in thickness between the layers, as well as in texture and grain size, allow specific layers to be identified. This is further aided by some units not being fully developed, whilst in other cases, some black and red layers are very faint or absent. Individual units are, on average, 10 to 13 m thick, whilst the average thickness of the different coloured layers is 1.5 m for black, 1 m for red and 10 m for white layers.

Hunt, Finch and Donaldson (2017) studied the layering in the Ilímaussaq Complex in Unit 0, and concluded that the bulk of the black and red layers developed through in situ crystallisation at the crystal mush to magma interface, whereas the white layer developed through a range of processes operating throughout the magma chamber. They concluded the layered kakortokite series did not form from a single chamber filling event, but that each new three layer unit was triggered by a new magma replenishment event. This is indicated by a sharp geochemical discontinuity to a relatively more primitive, halogen-rich magma across the boundary between the white layer at the top of Unit -1, and the basal black layer of Unit 0. From this boundary, upwards, the magma becomes progressively less primitive to the base of the next triplet. The sharp boundary between units -1 and 0 is interpreted to have formed from combined thermal and chemical erosion of a semi-rigid crystal mush at the top of Unit -1. The initial high concentration of halogens, as indicated by the chlorine-enriched eudialyte crystals in the black kakortokite layer, inhibited mineral nucleation, resulting in supersaturation of the magma. However, as the basal magma layer cooled through thermal equilibration, arfvedsonite was the first phase to nucleate, as it can crystallise at higher volatile concentrations. This took place, primarily in situ, at the crystal mush to basal magma interface, forming the basal black kakortokite layer, with a small, but progressively increasing number of arfvedsonite crystals growing in suspension above the basal layer and settling. The crystallisation of arfvedsonite that formed the black layer was accompanied by minor alkali feldspar, eudialyte and nepheline, and by the desaturation of arfvedsonite in the basal magma layer. However, the crystallisation of arfvedsonite consumed fluorine and chlorine and reduced the halogen concentration in the basal magma. This continuing decline in the halogen content would facilitate the nucleation of eudialyte, and with the desaturation of arfvedsonite, lead to the transition from black arfvedsonite to the overlying red eudialyte dominated kakortokites. This eudialyte crystallisation also took place in situ at the crystal mush to magma interface. The chlorine concentration in the basal magma decreased throughout the crystallisation of eudialyte, which is chlorine-rich. It is also interpreted to have been enhanced by the gradual equilibration of the basal magma layer with the resident magma of the main chamber above, where the coeval precipitation of sodalite in the Roof Series is suggested to have reduced the halogen concentration (Larsen and Sørensen, 1987). This continued halogen reduction, in combination with the eudialyte desaturation of the melt, is interpreted to have allowed alkali feldspar and nepheline to nucleate. This occurred both in situ at the crystal mush to magma interface, and in suspension in the main magma chamber above, to form the upper white kakortokite layer, above a gradational boundary. At this stage, the basal magma had equilibrated with the main magma chamber above and both were halogen-poor and of comparable density, and hence this latter layer developed through a range of processes operating throughout the magma chamber including density segregation (Hunt et al., 2017).

The primary eudialyte-group minerals form well-developed idiomorphic crystals with an average grain size of 0.5 to 1 mm. Most crystals exhibit complex, crystallographically controlled, fine, sub-µm oscillatory zoning, as well as concentric core to rim zonation. This zoning is associated with minor differences in Nb and LREE contents of <0.2 wt.% between light and dark sectors. Rims typically occur along specific faces of primary zoned eudialyte crystals. These rims are distinctly enriched or depleted in REE and presumably reflect changes in the REE-budget of the evolving (interstitial) melt in the final stages of crystallisation (Borst et al., 2014).

A large part of the original cumulus eudialyte has undergone late-stage replacement/alteration. The initial stage of this alteration occurs as irregular replacement along margins and cracks and is associated with crystallisation of fine-grained anhedral crystals of the Na-zircono-silicate catapleiite [(Na,Ca)2ZrSi3O9•2H20], as well as µm sized Ce- and Nb-rich phases. As alteration proceeds, an increasing volume of eudialyte is consumed until the grain is completely replaced and pseudomorphed by secondary phases. Relics of eudialyte were retained with their original composition in some pseudomorphs, although these remnants locally lost minor Na and Cl. In eudialyte pseudomorphs that were fully decomposed, several separate assemblages of secondary minerals can be distinguished. Most are dominated by catapleiite with ~35 wt.% ZrO2, ranging from a near pure Na end member to strongly calcic. Aegirine [NaFe(Si2O6)] is the principal Fe-bearing alteration phase in nearly all pseudomorphs. Nacareniobsite-(Ce) [Na3Ca3(Ce,La)Nb(Si2O7)2OF3] is found in most assemblages and hosts most of the Nb and REE that was in the original eudialyte. Both aegirine and nacareniobsite-(Ce) have near ideal end member compositions, in contrast to their magmatic counterparts, which show significant solid-solution trends in the aegirine-augite and rinkite-mosandrite-nacareniobsite-(Ce) series. Despite the degree of alteration and redistribution of the major components, Zr, REE and Nb, effectively fractionating them among the newly formed minerals, the bulk composition of the pseudomorphed eudialyte appears to be preserved (Borst et al., 2014).

• Slightly (Weakly) Layered Kakortokite, which is ~35 m thick and is virtually unlayered, grey and fine‐ to medium-grained (1 to 5 mm) with some faint black and red layers. The rock has a composition of an average kakortokite (Bohse et al., 1971; Bohse and Andersen, 1981). Schønwandt, Barnes and Ulrich (2023) show it to have a wavy to 'flaser-bedded' structure and that angular discordance occurs between individual bands. These structures, which are not observed in the Lower Layered Kakortokite, have been suggested to be the result of local current activity within the magma chamber.

• Transitional Layered Kakortokite, which is ~40 to 50 m thick, and passes gradually upward into the basal Intermediate Series lujavrites, represented by the aegirine lujavrite I unit. This transitional unit is agpaitic, meso- to fine-grained, laminated and shows variably developed sub-horizontal layering (Sørensen and Larsen 1987). The grain-size progressively decreases upwards from the Slightly (Weakly) Layered Kakortokite. The mafic minerals are acicular and slightly aligned, whilst primary aegirine is evident, increasing upward through the sequence into the aegirine lujavrite I unit. Six eudialyte-bearing layers have been mapped in the Transitional Layered Kakortokite to the SE of the Lakseelv Fault, labeled A to F in descending order (Bohse and Andersen, 1981). However, Demina (1979) reported nine such eudialyte-bearing layers, labelling them A to I in descending order to the NW of the same fault. The extra three red layers of Demina (1979) are in the lowermost part of the profile, with layers A to E being common to both studies. These extra lower 3 layers are regarded more likely to be part of the underlying Slightly (Weakly) Layered Kakortokite (Bohse et al., 1971; Schønwandt, Barnes and Ulrich, 2023). The lower five eudialyte-bearing units, E to I resemble the well developed black, red and white layers characteristic of the Lower Layered Kakortokite (as described above), occurring as a greyish kakortokite sequence enclosing the red layers, with local vague black and white layering. Layers E, F and G occur at ~5 m intervals, whilst H and I are 15 m apart. Layers E and G are 0.5 to 1 m thick with up to 50% eudialyte, whilst F, H and I are ~0.3 m thick with ≤20% eudialyte.

However, in contrast, the upper 4, layers A to D, are markedly different. The latter four are more or less equally distributed at 10 m spacings over a 50 m interval, separated by a dominantly grey to white kakortokite. They pinch and swell along strike, varying from 1 to 5 m in thickness, and are composed of a complex assemblage of rocks. The four main lithologies are:

i). pegmatite, the most common, composed of arfvedsonite, microcline laths, nepheline, natrolite and/or analcime; the latter two occurring as interstitial grains; the elongated, lath-shaped crystals are up to 5 cm long; the pegmatite is difficult to distinguish from naujaite autoliths, and has been interpreted to constitute a strongly altered naujaite;

ii). fine grained, sacchoroidal eudialyte-rich syenite intervals that are 0.2 to 1 m thick, and are composed of aegirine, analcime and minor coarse-grained microcline and/or nepheline.

iii). a distinctive fine- to medium-grained, melanocratic aegirine-feldspar rock with up to 20 to 30% coarse-grained corroded nepheline and microcline grains.

iv). naujaite-like autoliths that are coarse-grained and mesocratic, composed of microcline, nepheline, arfvedsonite and locally eudialyte, with a few poikilitic relicts of arfvedsonite oikocrysts.

These lithologies do not occur in a specific order. Aegirine is the dominant mafic mineral in layer A, whilst arfvedsonite dominates in layers B, C and D (Bohse and Andersen, 1981; Demina, 1979). Layer A is underlain by a 3 m thick band of aegirine lujavrite, which grades down into kakortokite, and is overlain by 1 m of ijolite (a nepheline aegirine-augite rock with minor eudialyte) which passes upwards into grey to white kakortokite, and then to the aegirine lujavrite I unit of the Intermediate Series.

The pegmatites, that are a major part of the red eudialyte layers A to D, bear a strong similarity to pegmatites developed within the lujavrites of the Intermediate Series, in mineral association, coarseness and texture. Both also have associated remnants of a poikilitic texture in the form of analcime crystals in eudialyte, reminiscent of poikilitic naujaite texture as well as naujaite autoliths. In making this comparison, Schønwandt, Barnes and Ulrich (2023) compare their observations of the eudialyte layers A to D in the Transitional Layered Kakortokite, to the description by Sørensen (1962) of the lujavrite intrusion followed by assimilation and metasomatic alteration of naujaite in the Intermediate Series higher in the pile. They regard the latter to represent a less advanced stage of the process. As such, Schønwandt, Barnes and Ulrich (2023) suggest these red eudialyte layers A to D are composed of partially assimilated autoliths of naujaite that have collapsed from the magma chamber roof and undergone syn-magmatic metasomatic transformation. As such, it is not simply the result of conventional igneous magmatic cumulate formation, as is inferred for the underlying Lower Layered Kakortokite (as described above). For more detail of the lujavrites of the Intermediate Series see the Kvanefjeld record.

The red, white and black eudialyte-bearing kakortokite of the Lower Layered Kakortokite, constitutes the main Tanbreez Zr, Nb, Ta, REE and Hf deposit.

The red eudialyte layers A to D of the Transitional Layered Kakortokite are a further potential source of ore (see resources below).

Drilling during 2024 indicated a number of potential higher grade zones associated with the resource, worthy of follow-up. These include:

i). The 5 m thick 0 Unit in the middle of the Lower Layered Kakortokite;

ii). The base of the Lower Layered Kakortokite;

iii). Area G, which covers an area of ~1 km2 containing 'extensive' late-stage pegmatites and pegmatite scree that have returned assays of as much as 147 ppm Ga2O3.

Additional mineralisation has been tested in what is known as the EALS Horizon within the naujaite sequence in the Roof Series of the complex to the north of the Lakseelv Fault. This unit contains high-grades and can be traced for approximately 3 km, with a thickness of up to 80 m. It contains a large number of pegmatites and has returned significant assay results, including grades exceeding 5% ZrO2 and >2% REO. Notably, the percentage of heavy rare earths within the rare earth fraction ranged up to 40.8%. From the available information (Barnes and Nielsen, 2020), this mineralisation appears to be related to a metasomatic front ahead of the intrusion of the late phase, volatile-rich, differentiated and fractionated lujavrite. Eudialyte within the naujaite, which is very soluble, and sensitive to pH change, is dissolved at the advancing, high pH metasomatic front, and is driven ahead of the front until the pH falls to an appropriate range to replace the host rock at that location and form a reinforced grade of eudialyte.

The mineralised Lower Layered Kakortokite sequence is exposed over an area of 5 x 2.5 km on the southern side of the Kangerdluarsuk Fjord. In the same area, the base of the mineralised unit (i.e., the top of the 'Black Madonna') is at ~20 m below sea level, and assuming 214 m as the average for the altitude of the top of the layered kakortokite, the total thickness becomes 234 m. A stratigraphic drillhole in the centre of the kakortokite mass in 2010 shows a total thickness of the Lower Layered Kakortokite to be 269 m. The Inferred Resource tonnages are based on the volume of Lower Layered Kakortokite calculated from the exploration and stratigraphic drilling, backed up by surface surveys to define the volume of mineralised material.

Grades have been estimated from surface sampling and diamond drilling programs. The surface sampling involved ~100 carefully-collected samples representing the entire exposed vertical sequence of the Lower Layered Kakortokite (Bohse, Brooks and Kunzendorf, 1971). This sampling indicated grades of between 1.4 and 1.9% ZrO2. Drillings along the southern coast of Kangerluarsuk Fjord, where the initial mining is planned, averaged 1.75% ZrO2, 0.18% Nb2O5 and 0.6% total REO, including yttrium. All of these elements are contained within eudialyte. The bulk assay data show a close linear correlation between ZrO2 and Nb, Ta and light and heavy REO. The distribution of the total REO in the Lower Layered Kakortokite indicates 30.9% heavy REE (including Y) and 69.1% light REE. U and Th are not elevated, only returning background assays of 20 and 53 ppm, respectively.

Mineralogical investigations have shown no or very little variation in the mineral species that make up the kakortokite and their properties. The chemical composition of eudialyte within the deposit has given it a magnetic susceptibility contrast with the two other main constituents of the ore, namely arfvedsonite and feldspar/nepheline, rendering it possible to produce a magnetic concentrate of eudialyte.

Mineral Resources

The published JORC Compliant Mineral Resource at the Tanbreez deposit (Tanbreez Mining Greenland A/S website, viewed February, 2025) are as follows:

Inferred Mineral Resource - 4.7 Gt @ 2.0% ZrO2, 0.60% REO, 0.20% Nb2O5, 0.03% Ta2O5 + HfO2.

This resource is hosted within the 20% Eudialyte fraction that can be magnetically upgraded to.

940 Mt @ 9 to 10% ZrO2, 2.5 to 2.7% REO, 1.0% Nb2O5, 0.15% Ta2O5 + HfO2.

The breakup of REE is:

• 27.19 % HREE - comprising 2.40% Gadolinium (Gd); 0.4% Terbium (Tb); 2.86% Dysprosium (Dy); 0.60% Holmium (Ho); 1.90% Erbium (Er); 0.30% Thulium (Tm); 1.80% Ytterbium (Yb); 16.63% Yttrium (Y); 2.4% Lutetium (Lu).

• 72.81 % LREE - comprising 18.01% Lanthanum (La); 35.27% Cerium (Ce); 3.80% Praseodymium (Pr); 13.03% Neodymium (Nd); 2.40% Samarium (Sm); 0.30% Europium (Eu).

Resources within the red eudialyte layers A to D of the Transitional Layered Kakortokite

8 Mt @ 1.8% ZrO2 (Schønwandt, Barnes and Ulrich (2023).

References are yet to be added

The most recent source geological information used to prepare this decription was dated: 2023.

This description is a summary from published sources, the chief of which are listed below.

© Copyright Porter GeoConsultancy Pty Ltd. Unauthorised copying, reproduction, storage or dissemination prohibited.

Tanbreez

|

|

|

|

Porter GeoConsultancy Pty Ltd (PorterGeo) provides access to this database at no charge. It is largely based on scientific papers and reports in the public domain, and was current when the sources consulted were published. While PorterGeo endeavour to ensure the information was accurate at the time of compilation and subsequent updating, PorterGeo, its employees and servants: i). do not warrant, or make any representation regarding the use, or results of the use of the information contained herein as to its correctness, accuracy, currency, or otherwise; and ii). expressly disclaim all liability or responsibility to any person using the information or conclusions contained herein.

|

Top | Search Again | PGC Home | Terms & Conditions

|

|