|

Yulong Porphyry Belt - Yulong, Malasongduo, Duoxiasongduo, Mangzong, Zhanaga, Narigongma |

|

|

Xizang - Tibet, China |

| Main commodities:

Cu Mo Au

|

|

|

|

|

|

Super Porphyry Cu and Au

|

IOCG Deposits - 70 papers

|

All papers now Open Access.

Available as Full Text for direct download or on request. |

|

|

The NNW trending Yulong Belt of Eocene porphyry copper deposits extends over an interval of ~300 km and a width of 15 to 30 km in the North Qiangtang Terrane of the Himalayan-Tibetan section of the East Tethyan Orogenic Belt in eastern Xizang (Tibet), 550 km ENE of Lhasa and 500 km west of Chengdu, in China.

The Yulong Porphyry Belt hosts one giant (Yulong), two medium to large (Malasongduo and Duoxiasongduo) and two small to medium sized deposits (Mangzong and Zhanaga), as well as >20 other mineralised porphyry bodies.

The Yulong Belt forms the northern segment of the broader, >1500 km long Jinshajiang-Ailaoshan-Red River Metallogenic Belt, which also includes the Ailaoshan-Red River Belt to the south and SE, following the same narrow Jinshajiang-Honghe alkaline-rich porphyry belt string of intrusions that includes the hosts to both lines of deposits (Hou et al., 2003, 2007; Deng et al., 2010, 2014; Xu et al., 2012).

Further porphyry style mineralisation is found to the north-west as a continuation of the Yulong Belt in the North Qiangtang Terrane, including the low grade, Mo-rich Narigongma porphyry deposit, southern Qinghai, Tibet, ~400 km NW of Yulong.

The East Tethyan Orogenic Belt of central to southeast Asian is part of the greater Tethyan Orogenic Belt that extends across Eurasia and northern Africa, from Indochina to the Atlas Mountains of Morocco. Other significant porphyry clusters and mineral belts within the East Tethyan Orogenic Belt include the Duolong Cluster within the enclosing Bangong Co-Nujiang Mineral Belt, which are to the west of the Yulong Porphyry Belt, the Ailaoshan-Red River Belt and the

Yidun or Zhongdian Arc, and NW of the Gangdese Belt.

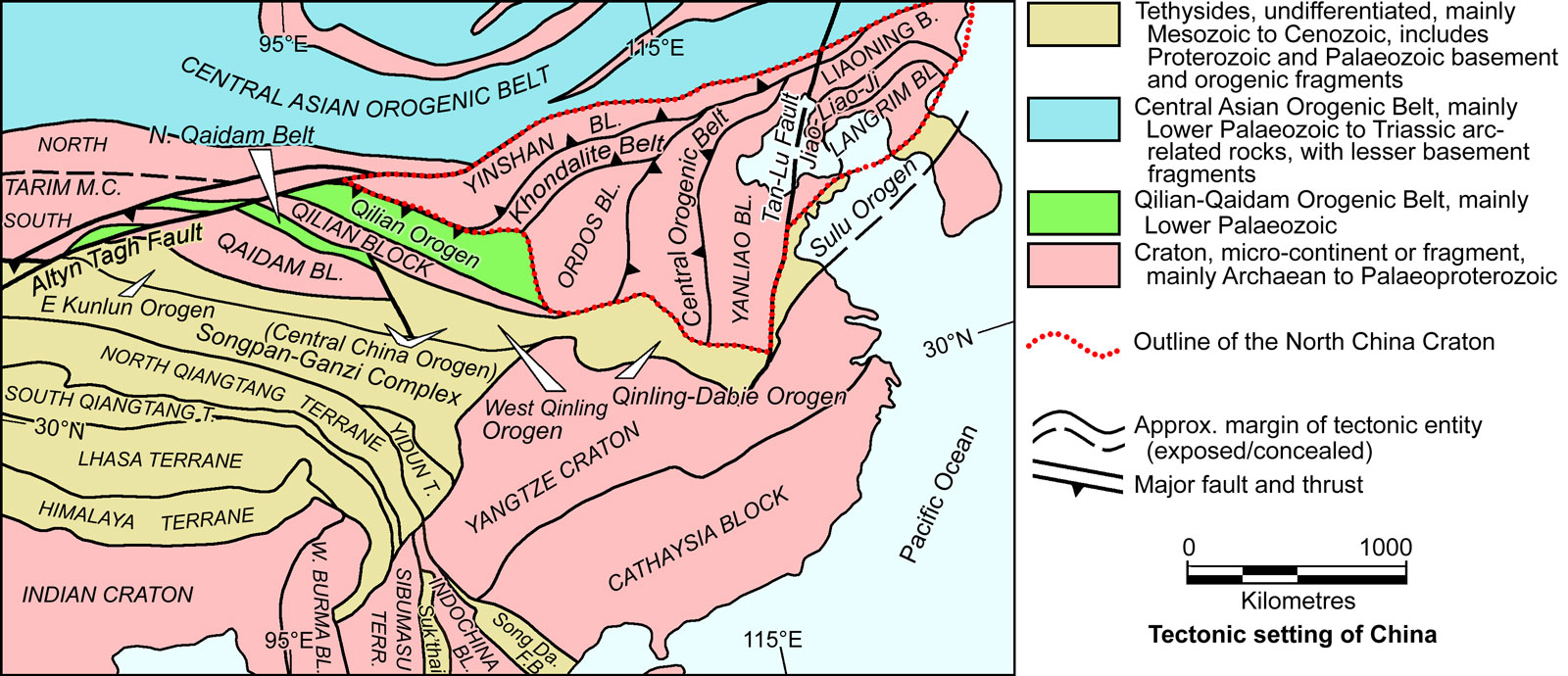

Regional Setting

Prior to the advancing India Craton encroaching upon, indenting, attenuating and 'bending' the southern margin of the East Tethyan Orogen in the Early Cenozoic, the latter is interpreted to have had a near linear, generally WNW-ESE trending configuration. At that stage the Indochina and Changdu-Simao (North Qiangtang) cratonic blocks were a single linear micro-continental sliver accreted to the southern margin of the South China Block in the east, and the Songpan-Garze Terrane to the west, across the continuous Jinshajiang-Ailaoshan Suture (see the Tectonic Setting image below). Deng et al. (2014) suggest the South Qiangtang Sub-terrane was a separate sliver accreted to the Indochina-Changdu-Simao cratonic sliver, across the Longmu Co-Shuanghu Suture Zone, but was confined to the north and west only. To the south and east, the latter suture forks into the composite Changning-Menglian and Inthanon Suture Zones to the west and the Jinghong Suture to the east flanking the Sukhothai Arc which separates the Indochina and Sibumasu (or Shan-Thai) cratonic terranes. Deng et al. (2014) also suggest the Lhasa and Sibumasu terranes are the same cratonic microcontinent, separated from the South Qiangtang Sub-terrane in the west by the Bangong Co-Nujiang Suture (also known as the Nijiang-Bitu Suture to the SE). This then merges to the south with the Changning-Menglian-Inthanon Suture Zone, as the South Qiangtang Sub-terrane pinches out. To the south again, the West Burma Cratonic Block is accreted to the west of the Sibumasu (or Shan-Thai) Cratonic Terrane across the Luxi Suture Zone.

The Yidun, or Zhongdian Terrane, which now has a NNW tapering, wedge shape, is ~550 km long and NNW-SSE elongated. It is located to the NE of the North Qiangtang Sub-Terrane (and its constituent Changdu-Simao Continental Block), separated by the Jinshajiang Suture. See the separate Yidun or Zhongdian Arc record for a description.

See the Regional and Continental Setting of the Ailaoshan-Red River Belt record for a more detailed outline, including the chronology of the progressive accretion on the southern margin of the Asian Plate.

The composite Qiangtang Terrane, within which the Yulong Belt is located, comprises a collage of continental blocks separated by volcano-plutonic complexes. It is separated from the Lhasa Terrane to the west and SW by the ophiolite bearing Bangonghu-Nujiang Suture, and from the Songpan-Garze Terrane in the NE and Yidun Terrane to the east by the Jinshajiang Suture. The bounding sutures are of Late Palaeozoic to Mesozoic age.

In the Yulong area, the composite Qiangtang Terrane is internally composed of the South Qiangtang and Changdu-Simao continental blocks, to the SW and NE respectively, separated by the Permian to Triassic Zuogong-Jinghong volcanic arc sequence. The Changdu-Simao continental block is separated from the Jinshajiang Suture to the east by the Permian to Triassic Jiangda-Weixi volcanic arc. The Changdu-Simao block and the two bounding volcanic arc sequences together are referred to as the North Qiangtang Sub-terrane.

The western section of the Qiangtang Terrane is characterised by high-pressure metamorphic rocks and contains late Palaeozoic marine strata, whereas the eastern part is overlain by Triassic to Jurassic shallow-marine carbonate and arc volcano-sedimentary sequences such as those of the Changdu-Simao Basin (Liu, 1988).

The Changdu-Simao continental block, which hosts the Yulong Porphyry Belt, comprises a folded, 2000 to 5000 m thick succession of Proterozoic and Lower Palaeozoic crystalline basement. The Proterozoic basement is predominately composed of 2200 to 1594 Ma lower amphibolite facies, and 999 to 876 Ma upper greenschist facies metamorphic rocks (Wang et al., 2000). These are overlain by folded Lower Palaeozoic rocks which mainly consist of a Lower to Middle Ordovician, low grade metamorphosed sequence of flyschoid sandy slate and carbonate rocks. Devonian to Late Triassic (to Jurassic) cover rocks are also widespread, comprising a 3000 m thick suite of platform transitional facies of marine carbonate and clastic sedimentary and volcanic rocks.

The Permian to Triassic Jiangda-Weixi arc volcano-sedimentary sequence to the east of the Changdu-Simao continental block, and the Jinshajiang Suture on the eastern margin of the terrane (Liu et al., 1993; Mo et al., 1993; Li et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2018), are both unconformably covered by sedimentary rocks of a strike-slip pull-apart basin that was filled by an Upper Triassic flyschoid complex that includes clastic and lime-dolostone beds of the Changdu-Simao and related basins. These rocks are locally overthrust onto folded crystalline basement.

The Permian to Triassic Zuogong-Jinghong arc sequence on the western margin of the Changdu-Simao continental block is the product of eastward subduction of the Lower Palaeozoic (505 to 492 Ma; Hu et al., 2014) Lancangjiang oceanic slab (Liu et al., 1993; Mo et al., 1993). It is covered by a 3000 m Devonian to Permian sequence of basal molasses-type clastic rocks, platform facies carbonate rocks, and coal-bearing sedimentary rocks (Wang et al., 2000). Zhao (2015) suggests the Lancangjiang oceanic slab was subducted both to the SW below the South (or West) Qiangtang block, and NE below the Changdu-Simao continental block.

The south western margin of the Zuogong-Jinghong arc sequence is occupied by the Longmu Co-Shuanghu Suture zone, composed of Palaeozoic, mainly Ordovician to Silurian, ophiolites (e.g., Zhai et al., 2010; Zhao, 2015).

The south western margin of the Zuogong-Jinghong arc sequence is occupied by the Longmu Co-Shuanghu Suture zone, composed of Palaeozoic, mainly Ordovician to Silurian, ophiolites (e.g., Zhai et al., 2010; Zhao, 2015).

The South (or West) Qiangtang continental block to the SW of the Longmu Co-Shuanghu Suture is composed of a largely buried older basement overlain by an Ordovician to Jurassic cover sequence and an obducted subduction mélange (Wang and Wang, 2001; Zhao et al., 2014; Zhai et al., 2011). Upper Carboniferous to Lower Permian glaciomarine rocks of this sequence contain fauna with a Gondwana affinity, in contrast to the Changdu-Simao Block of the North Qiangtang Sub-terrane which is of Tibet/Asian origin (at least in its northern half). This suggests the South Qiangtang Block was split from Gondwana and transported north during subduction on the trailing edge of the Lancangjiang ocean (Zhao, 2015). By the Upper Permian, warm water Cathaysian fauna indicates that the block may have been connected to the Cimmerian (Tibet/Asian) continent (Metcalfe, 2011). All of these units are unconformably overlain by Late Triassic limestone and Early Jurassic siliciclastics and carbonates which, in turn, unconformably overlie the older units (Zhao et al., 2015). These overlying Jurassic to Early Cretaceous marine sedimentary rocks were deformed and uplifted due to collision between the Lhasa and Qiangtang terranes across the Bangonghu-Nujiang Suture (Kapp et al., 2007).

The Lhasa Terrane, which also has fauna of Gondwana affinity, is separated from the South Qiangtang Sub-terrane by the Bangonghu-Nujiang suture (Chang and Zheng, 1973; Allegere et al., 1984; Dewey, 1988; Pierce and Mei, 1988). This terrane was shortened by ~180 km during the India-Asia collision from ~70 Ma (Murphy et al., 1997; Yin and Harrison, 2000) and includes the Gangdese volcano-magmatic arc, composed of Late Paleocene, Early Cretaceous and Early Tertiary granite batholiths, Eocene calc-alkaline volcanic rocks and Miocene ultrapotassic intrusions. See the separate Gangdese Belt record for detail.

The Songpan-Garze Terrane is located to the NE of the Qiangtang Terrane, and is also bounded by the South China/Yangtze, North China and Qaidam continental blocks to the east, NE and north respectively, with the the Kunlun/Central China Orogen occurring on its north margin with the Qaidam Block. It is covered by >3000 m of Upper Triassic marine turbidites, and is dislocated by numerous thrusts. It has traditionally been interpreted to be floored by oceanic crust, although more recent seismic and intrusive geochemistry suggest it may be underlain by Cathaysian-type continental basement, at least in its eastern sections (Zhao, 2015). Subduction of Songpan-Garze oceanic floor, both northward below the Kunlun-Qaidam blocks, and southward below the Qiangtang Terrane, commenced during the Carboniferous (e.g., Li et al., 2002) and ceased in the Late Triassic (Pullen et al., 2011).

The Yulong Porphyry Belt lies to the north of the northeastern corner of the advancing, NE vergent, triangular, Indian plate. At this corner, the northern, east-west trending margin of the advancing plate changes to SE trending. As a consequence, the tectonic pattern of WNW-ESE trending, NE vergent thrusting in the central Tibet Plateau, is transformed east of this corner into dominant NNW-SSE to north-south trending dextral strike slip faults. Displacement on some of these structures was as much as 500 km, e.g., the Jinshajiang Fault that follows the suture of the same name. The oblique continental collision also resulted in the generation of escape tectonics in SE Tibet and Indochina caused strain partitioning and development of a series of NNW-trending sinistral faults and shear zones in and across the Yidun Terrane and Qiangtang Terrane (Yang et al., 2016; 2018).

More than 100 porphyry intrusions have been recognised in the Changdu-Simao continental block (Tang and Luo, 1995). These porphyry bodies commonly occur as steeply dipping to vertical pipes with small outcrop areas of <1 km2.

Shells of crypto-explosive breccias are commonly developed around mineralised porphyry bodies. K-Ar dating of these porphyries has defined three main periods of emplacement: 55.0 to 48.2, 44.0 to 35.8 and 34.0 to 33.7 Ma. These intrusions are typically emplaced into Triassic volcanic and sedimentary rock cover at relatively shallow emplacement depths, generally 1 to 3 km from the paleosurface. A parallel string of similarly small, but un-mineralised 45 to 30 Ma syenitic alkali-rich intrusions are developed ~40 km to the SW.

The margins of the Changdu-Simao block are occupied by several strike-slip pull-apart basins, including the Gonjo Basin on the eastern side, and the Nangqen and Lawu basins on the western side, each containing sequences of >4000 m of Tertiary gypsum-bearing red molasse intercalated with 42.4 to 37.5 Ma (K-Ar; Zhang and Xie, 1997; Wang et al., 2000) alkaline volcanic rocks. These volcanic rocks have a similar geochemical and isotopic composition to the Yulong porphyries and the two are regarded as being coeval (Jiang et al., 2006).

The Eocene porphyry intrusions of the Yulong Porphyry Belt appear to have emplaced in a post collisional transpressive regime, distal to any subduction activity, but controlled by a series of active sinistral and dextral strike slip faults that were a direct response to the coeval Indo-Asian collision. These faults occur both on the margins of and within the Changdu-Simao block.

This transpression and consequent regional scale strike-slip fault system is interpreted to have caused changes in the geometry of the lower crust and subcrustal lithospheric mantle (SCLM), triggering processes that led to the melting of the lower lithospheric mantle to form the Cenozoic porphyries. Seismic profiles across the Qiangtang Terrane indicate the major strike slip faults are translithospheric and resulted in Moho displacements of 2 to 3 km (Tang et al., 1995; Fei, 1983). Jiang et al. (2006) suggest this is sufficient to cause upwelling of asthenosphere below the upthrown fault blocks, which triggered melting. Conversely, downthrow of blocks of lower SCLM to greater depths and temperatures also facilitated melting. Although there was no active Eocene subduction below the zone of melting, fertilised SCLM may have been retained from the earlier Permo-Triassic subduction (as indicated by decoupled Hf and Sr-Nd-Pb isotopic compositions reported by Jiang et al. (2006) and thus contributed to the production of permissive melts (Jiang et al., 2006).

Detailed analyses by Jiang et al. (2006) suggest the host porphyry at Yulong was the product of low degree (1 to 5%) partial melting of a metasomatised phlogopite-garnet-clinopyroxene lithosphere at anomalously high temparatures of >1200°C (based on clinopyroxene phenocryst geothermometry) and depths of >100 km (inferred on the basis of the metasomatic volatile phase [phlogopite-carbonate] relations). A mass balance estimate by Lian et al. (2009) assumed that i). the source felsic magmas of the parental batholith contained a minimum of 100 ppm Cu; ii). 80% of this Cu was extracted and iii). 80% of the extracted Cu was precipitated in the deposit. On these assumptions they concluded a >70 km3 source parental batholith would be required to supply the 6.5 Mt of Cu resource in the Yulong deposit, plus at least as much again in the surrounding low grade halo and satellite prospects. Furthermore, >1500 km3 of metasomatised SCLM would need to undergo 5% partial melting to generate the magma to produce this batholith, assuming 100% efficiency of melting and upward transfer and focussing into the parental batholith.

The Yulong Monzogranite Porphyry is characterised by high K2O contents (4.15 to 8.06 wt.%), high K2O/Na2O ratios (>1.0), alkali enrichment (K2O+Na2O >8 wt.%) and enrichment in LREE and LILE, interpreted to indicate shoshonitic and high-K calc-alkaline signatures (Zhang et al., 1998). These rocks have high SiO2 and Al2O3, and low MgO, high Sr/Y and La/Y ratios, coupled with enrichment in Sr, depletion in Y and Yb, low HREE, and no Eu anomalism, suggesting geochemical affinity with adakite (Defant and Drummond, 1990; Hou et al., 2003, 2004, Jiang et al., 2007). They also have a limited range of δNd(t) (-2.2 to -4.2) and relatively high (86Sr/87Sr)i of 0.7058 to 0.7068 (Zhang and Xie, 1997; Zhang et al., 1998), suggesting a basaltic lower-crustal source which was thickened and partially melted by the Indo-Asian collision at 65 to 50 Ma (Hou et al., 2004).

Hou et al., 2003 suggest a 20 km thick, gently dipping, high seismic velocity layer 50 to 60 km beneath section of the Yulong Belt (Zhong et al., 2000, 2001) may represent the relict subducted Jinshajiang oceanic slab. The Jinshajiang Ocean separated the Yidun and Qiangtang Terrane and was subducted to the west below the latter until its closure at ~245 Ma. Wang et al. (1995) and Zhang and Xie (1997) estimated that TCHURNd source ages of ore-bearing porphyries and alkali rich intrusions in the Yulong and Ailaoshan-Red River porphyry belts as from 230 to 250 Ma. The depth of the Yulong magmas source has been estimated to be 48 to 60 km by mineral melt equilibrium calculation (Ma, 1990). Hou et al., 2003 suggest this slab may have been responsible for fertilisation of the mantle wedge and SCLM that underwent partial melting to form the Yulong parental batholith.

YULONG PORPHYRY BELT

The Yulong Porphyry Belt is ~300 km long, by 15 to 30 km wide and is ~550 km ENE of Lhasa. It contains >9 Mt of Cu metal, 0.2 Mt of Mo and 40 t of Au (Tang and Luo, 1995; Bai et al., 1996; Hou et al., 2003, 2006, 2007; Liang et al., 2006, 2009) within a number of porphyry Cu-Mo deposits and prospects that form the northern half of the string of mineralised porphyries within the Changdu-Simao continental block described above.

Other significantly mineralised porphyries are found ~300 km further SSE in the Ailaoshan-Red River Belt, in the southern extremities of this same string of intrusions, and include the Beiya Au-Cu and Machangqing Cu-Mo and Au deposits which occurs near the intersection between the southern Changdu-Simao block and the major NW-SE Red River Fault.

The porphyry deposits of the main Yulong Porphyry Belt are characterised by pyrite-tourmaline-quartz cemented breccias (Tang and Luo, 1995) that are associated with composite multiphase intrusions, usually dominated by an early quartz monzonite and late syenogranite stages (Zhang et al., 1998). The significantly mineralised intrusions have porphyritic textures, defined by plagioclase, K feldspar, amphibole, mica and quartz phenocrysts in a medium grained phanerocrystalline groundmass of similar mineralogy. Accessory minerals include magnetite, titanite, apatite and zircon.

These porphyries, vary from mafic to felsic in composition (Jiang et al., 2006). The key deposits are described below:

Yulong Cu-Au-Mo (#Location: 31° 37' 33"N, 97° 47' 44"E)

Geology - The Yulong porphyry copper deposit is located just north of the centre of the Yulong Porphyry Belt, associated with the largest mineralised Eocene intrusive complex in the Yulong belt, a composite intrusion that forms a small stock with a surface area of about 0.64 km2. This stock intruded a sequence of Triassic marine clastic and carbonate rocks at the southern end of the N- to NW-trending Hengxingcuo anticline, which provided a structural control for the emplacement and distribution of >40 porphyry intrusions. It is composed of three successive intrusive phases:

• Monzogranite Porphyry - which forms the bulk of the stock and is the earliest intrusion. It is composed of ~40 to 50% phenocrysts, comprising 10 to 15%, 5 to 30 mm K feldspar; 25 to 35%, 0.5 to 8 mm plagioclase; 1 to 5%, 1 to 5 mm quartz; 2 to 5%, 0.5 to 3 mm biotite; and 1 to 5%, 0.5 50 5 mm hornblende, in a 50 to 60% matrix comprising 0.01 to 0.2 mm quartz, K feldspar and plagioclase. A weighted mean age of this porphyry, from 19 analyses, was 42.0±0.3 Ma (206U/238Pb zircon; Chang et al., 2017).

• K feldspar Granite Porphyry - which occurs as <50 m wide dykes that intrude quartz veined Monzogranite Porphyry and surrounding hornfels with sharp contacts. Unidirectional solidification textures are occasionally developed in the K feldspar Granite Porphyry close to the contact zone with the Monzogranite Porphyry. The two intrusive phases can be easily distinguished by the abundance and grain size of phenocrysts, even when they are overprinted by intense supergene kaolinite leaching. The K feldspar Granite Porphyry is composed of ~40 to 50% phenocrysts, comprising 2 to 3%, 2 to 10 mm K feldspar; 10 to 25%, 0.5 to 4 mm plagioclase; 3 to 7%, 1 to 2 mm quartz; 1 to 3%, 0.25 to 1 mm biotite; and only rare hornblende, in a 70 to 80% matrix comprising 0.05 to 0.1 mm K feldspar and quartz. A weighted mean age of this porphyry, from 18 analyses, was 41.2±0.3 Ma (206U/238Pb zircon; Chang et al., 2017).

• Quartz Albite Porphyry - occurs as dykes ranging from <5 to 25 m in thickness which typically truncate quartz veins hosted in the two preceding intrusive phases, and frequently contain angular to subrounded Monzogranite Porphyry and vein quartz xenoliths. When unaltered, it is darker than the other two porphyries due to the lower proportion of phenocrysts and the presence of abundant magmatic biotite in the groundmass. Most of these dykes have undergone intense sericitic alteration with only quartz phenocrysts and/or vein quartz xenoliths surviving. Quartz veins are only rarely found within this porphyry. It is composed of ~15 to 20% phenocrysts, comprising 1 to 2%, 3 to 10 mm K feldspar; 10 to 15%, 0.5 to 6 mm plagioclase; 1 to 2%, 1 to 5 mm quartz; 3 to 7%, 0.25 to 2 mm biotite; and only rare hornblende, in a 80 to 85% matrix comprising 0.01 to 0.05 mm quartz K feldspar; plagioclase and biotite. A weighted mean age of this porphyry, from 14 analyses, was 40.2±0.3 Ma (206U/238Pb zircon; Chang et al., 2017).

Mineralisation - The mineralisation associated with the intrusion at Yulong occupies a volume of 1000 x 600 m in plan area, x ~800 m deep, centred on the NNW-SSE elongated, steep, pipe-like porphyry stock with a similar plan area. The ore zone is mainly within the outer and upper porphyry stock, but straddles the contact with the proximal hornfelsed Triassic country rocks. It has an asymmetric, north-south elongated, inverted bowl shape in three dimensions, with the highest economic grades occurring in the southeastern part of the deposit, extending downward to 4000 masl. The highest preserved part of the inverted bowl ore zone, which has a base and sides that are 200 to 600 m thick, is at an elevation of ~4800 masl. It encloses and overlies a subeconomic to barren core (i.e., <0.3 wt.% Cu) in the central part of the stock. The top of this barren core is at ~4300 to 4400 masl, with grades of <0.09% Cu, and <0.01% Mo (Tang and Luo, 1995; Bai et al., 1996).

The main hypogene Cu-Mo mineralisation within the porphyry stock principally comprises veins/veinlets, vein stockworks and disseminations of molybdenite and chalcopyrite, associated with K silicate alteration, and pyrite ±chalcopyrite veins and disseminations accompanying a late phyllic phase. In hornfels surrounding the stock below the near surface carbonate facies, the pyrite-chalcopyrite stockwork has an increasing ratio of pyrite:chalcopyrite outwards until pyrite dominates.

A late, structurally controlled, high sulphidation Cu-Au mineralisation stage is associated with advanced argillic alteration. It was controlled by a subhorizontal to gently outward dipping breccia horizon developed along a marginal fracture zone near the roof of the stock, and extending laterally outward along a gently dipping contact between limestone and underlying hornfelsed sandy slate. This breccia horizon was partly eroded during post-mineral uplift, which removed its central section, with the remnant forming a ring-shaped lenticular zone surrounding the core of the stock. This ~200 to 300 m wide and 20 to 100 m thick annulus of stratabound mineralisation largely occurs within Late Triassic sedimentary rocks, and encircles the porphyry intrusion. It is contained within carbonate rich facies that have been altered to skarn and marble. The skarn is fine-grained, composed of massive grossularite cut by vein and disseminated pyrite-chalcopyrite, that has been converted into a yellow-green clay advanced argillic assemblage with residual grossularite (Hou et al., 2006). It contains much of the high-grade Cu-Au ore (~3 Mt of Cu in ~60 Mt of ore @ 4.74% Cu, 4.5 g/t Au; Tang and Luo, 1995,) much of which is preserved within the surrounding altered Triassic country rocks. The skarn also contains appreciable amounts of magnetite with lenses of >30 wt.% Fe, and a skarn iron ore reserve of 86 Mt (Ma, 1990; Tang and Luo, 1995).

This structure is interpreted to have been produced by hydrothermal brecciation largely due to fluid overpressure and boiling. The alteration and mineralisation has been attributed to a CO2 rich, low-temperature (<350°C), low-salinity (<12 wt.% NaClequiv.) cooled and refluxed magmatic (and/or meteoric) fluid (Hou et al., 2006). The accompanying texture-destructive advanced argillic alteration is characterised by an assemblage that included quartz, kaolinite, dickite-endellite, montmorillonite, hydromica and minor alunite. It was predominantly developed within the breccia horizon, and partially overprints both earlier K silicate and phyllic alteration. Associated high-sulphidation epithermal mineralisation is characterised by chalcocite, tennantite, covellite, bornite and chessylite [Cu3(CO3)2(OH)2] with minor pyrite and molybdenite. Some peripheral chalcopyrite-galena-sphalerite occurs, farthest from the intrusive. The epithermal fluids caused dissolution of early stage Cu-Mo sulphides and re-precipitation within the intense advanced argillic alteration halo. Fine grained molybdenite is either intergrown with bladed hypogene kaolinite and alunite, or occurs in sparse quartz veins, whilst copper was mainly deposited in chalcocite, tennantite and covellite, commonly replacing early disseminated chalcopyrite-pyrite assemblages. The high sulphidation assemblage is more abundant in sparse quartz veins within the advanced argillic halo, including chalcocite-dickite-quartz, chalcocite-chessylite-kaolinite-alunite, tennantite-bornite-covellite, pyrite-bornite-quartz, molybdenite-kaolinite and molybdenite-quartz in the porphyry stock, but also occurs as rare fine-grained crystals intergrown with kaolinite and quartz in a dickite-enriched advanced argillic alteration envelope (Hou et al., 2006).

Supergene mineralisation - The upper sections of the deposit, particularly the annulus of high sulphidation Cu-Au mineralisation, has been subjected to supergene modification. The following, generally horizontal zones, are described by Hou et al. (2006):

• Upper leached cap which is 3 to 5 m thick, and dominated by jarostic, hematitic and goethitic limonite and associated clay minerals. It is overlain by crystalline limestone and grades downward into the malachite-rich zone.

• Malachite zone, that is 2 to 12 m thick and is predominantly composed of malachite, covellite, digenite and minor limonite clasts, with grades of from 6 to10% Cu. The malachite-digenite assemblage has the highest Cu grades, reaching 23% Cu (Tang and Luo, 1995). Disseminated malachite is found in various hydrothermal breccias and advanced argillic altered rocks, whereas veined malachite mainly fills fissures in porous advanced argillic alteration halos. The clasts in the hydrothermal breccias in this zone include limestone with minor skarn, hornfels and porphyry clasts, all of which have which undergone texture-destructive advanced argillic alteration.

• Limonite zone, which ranges from 2 to 63 m in thickness and has a characteristic red-brown colour. It comprises powder-like limonite interbedded with massive limonite layers. The former includes jarosite and clay minerals, whilst the latter is dominated by undifferentiated limonite with minor jarosite, hematite and remnant magnetite. It has variable grades, ranging from 0.5 to ~2.0 %, averaging ~1.5% Cu and most likely represents and earlier supergene sulphide enrichment zone.

• Chalcocite zone, which is from 6 to 13 m thick, is characterised by a blue-grey colour and has an average grade of 5.4% Cu. It is composed of mixed hypogene and supergene sulphides associated with a dickite-endellite rich advanced argillic envelope. It has brecciated, massive, banded and disseminated structures. The upper section is characterised by disseminated and fracture-controlled cuprite, covellite, digenite, delafossite [CuFeO2] and minor chalcocite as coatings on pyrite and trace chalcopyrite. The middle section of the layer is a transition between supergene and hypogene facies. The supergene sulphides comprise disseminated and powder like chalcocite, with minor digenite filling pores in clay assemblages or rimming pyrite and chalcopyrite. The hypogene sulphide facies includes chalcocite, tennantite, covellite, bornite and minor pyrite. The hypogene chalcocite is commonly intergrown with bladed hypogene endellite and minor hypogene covellite. It also occurs along hairline pyrite-veinlets with kaolinite and covellite in the matrix of hydrothermal breccias, and in massive veins in association with tennantite, bornite and minor pyrite. The Au- and Ag-rich ores developed near the redox boundary between supergene and hypogene sulphide facies, with Au and Ag are concentrated in the latter at grades of 4 to 6 g/t Au and 810 to 2070 g/t Ag (Tang and Luo, 1995).

• Hypogene zone, which in the stratabound annulus to the porphyry stock occurs as a 7 to 10 m thick pyrite-chalcopyrite lens grading 1.4 to 2.7% Cu, overlying a 3.5 m thick skarn Cu lens. The pyrite-chalcopyrite band grades upward into a thin (<1 m thick) advanced argillic layer, dominated by an endellite-hydromica-alunite assemblage, where hypogene sulphides are replaced by chalcocite at the base of the chalcocite zone. The skarn Cu mineralisation developed within carbonate rocks along and above gently dipping contacts with underlying hornfelsed sandstone.

Alteration - The Yulong porphyry has undergone strong hydrothermal alteration. Tang and Luo (1995) recognised five zones of alteration:

i). Lower potassic, producing fine grained secondary K feldspar, biotite, albite and magnetite in the relatively barren core of the porphyry intrusion at elevations below 4300 masl (Tang and Luo, 1995);

ii). Upper potassic, developed within the upper part of the Yulong porphyry intrusion, above 4300 masl, characterised by secondary quartz, K feldspar and biotite, with minor magnetite, actinolite, epidote, albite, carbonate and anhydrite, and associated quartz-sulphide (chalcopyrite + bornite + pyrite)-magnetite mineralisation. An outward decreasing intensity of potassic alteration is reflected by the increasing in the preserved porphyry texture, and a trend towards more hydrothermal biotite and lesser hydrothermal K feldspar ± quartz.

iii). Propylitic, which formed epidote, chlorite, albite, pyrite and carbonate minerals, mainly occurring as fine-grained aggregates or veinlets in the weakly metasomatized surrounding sedimentary rocks, overprinted peripheral hornfels, but also locally the early potassic alteration zone;

iv). Phyllic, which occurs as a pervasive assemblage of quartz-pyrite-muscovite ± illite ± kaolinite, resulting in the complete to partial destruction of the precursor potassic assemblages and original texture, together with the development of abundant quartz-sulphide-sericite veinlets. These veinlets have reopened earlier magnetite-bearing veins, resulting in partial replacement of magnetite by pyrite. They formed peripheral to and partly superimposed on the second K-silicate alteration zone, being found near the margins of, but mainly within the intrusive;

v). Intermediate Argillic, composed of illite-montmorillonite ±kaolinite that variably replace plagioclase phenocrysts but not affect K feldspar and biotite. It appears to be unrelated to any vein type and is not accompanied by sulphides. It commonly overprints moderate potassic alteration but is less common in the intensely potassic rocks where no plagioclase survives. Intermediate argillic assemblages typically formed at relatively low temperature (<200°C; Seedorff et al., 2005). It is developed in all porphyry intrusions at Yulong, indicating some of them are products of the Late Stage. However, the lack of spatial association with Quartz Albite Porphyry dykes is taken to suggest intermediate argillic alteration might also be the product of retrograde processes during the Early and Transitional stages.

vi). Argillic to Advanced Argillic. Advanced argillic alteration is structurally controlled and represented by hydromica, montmorillonite, dickite-kaolinite, halloysite and vuggy quartz with associated chalcocite, covellite and molybdenite mineralisation (Tang and Luo, 1995), which occurs mainly in the contact zone with the surrounding Late Triassic sedimentary rocks. It is found both in the Monzogranite Porphyry and K feldspar Granite Porphyry and occurs in deep parts of the deposit at <4300 masl. As such it may be a late-stage event.

Supergene kaolinite ± montmorillonite argillic alteration is extensively developed in the upper 50 to 200 m deep sections of the deposit in the shallow strong supergene leached zone.

Veining - Chang et al. (2017) have grouped vein formation, hydrothermal alteration and Cu-Mo mineralisation into early, transitional and late stages with respect to the intrusive phases and the progression of mineralisation and alteration styles. They have also identified repeated cyclical sequences of vein types following the intrusion of the Monzogranite Porphyry, possibly involving more than one cycle, and K feldspar Granite Porphyry. The vein types described are broadly consistent with those described by Gustafson and Hunt (1975) and Gustafson and Quiroga (1995) at El Salvador, and Sillitoe (2010), although the A1, A2 and A3 veins of Chang et al. (2017) would appear to be closer to the A, B and C veins respectively of the other authors and will be denoted as such below. The characteristics of the three main veining and intrusive stages are as follows:

► Early Stage veins and associated mineralisation, which are accompanied by potassic alteration and predate the intrusion of K feldspar Granite Porphyry dykes. The principal vein types as described by Chang et al. (2017), are:

• M (Magnetite) veins - 1 to 8 mm thick, commonly lacking well defined walls and having irregular internal structure. These veins are barren and characterised by major magnetite with accompanying quartz, biotite and K feldspar, and minor actinolite, rutile, diopside and ankerite. They are cut by EB and A veins of the Early Stage, and by Transitional Stage veining. These veins are rare and are only found below the ore zone.

• EB (Early Biotite) veins - 0.5 to 10 mm thick, with irregular or straight walls, containing granular quartz intergrown with biotite. These veins are generally barren, but may be overprinted by later chalcopyrite, pyrite or molybdenite. They are characterised by major quartz and biotite, and minor rutile and apatite, and no selvage. They cut M veins, but are cut by A, B and C veins of the Early Stage, and by Transitional Stage veining. Not common, but occur throughout the deposit.

• A veins (the A1 veins of Chang et al., 2017) - 5 mm to 1 m thick, with irregular or straight walls, containing quartz with disseminations of K feldspar and trace biotite. These veins are generally barren, but may be overprinted by later chalcopyrite, pyrite or molybdenite. They are characterised by major quartz and K feldspar, with minor biotite, rutile and anhydrite, and mostly have no selvage. They cut most M and EB veins, but are cut by B and C veins of the Early Stage, and by Transitional Stage veining. These are the dominant veins in the barren core.

• B veins (the A2 veins by Chang et al., 2017) - 1 to 30 mm thick, with straight walls, containing fine, anhedral, granular quartz with molybdenite, chalcopyrite and pyrite disseminations or aggregates in quartz. These, with C veins are the dominant veins in the main ore zone, and are commonly associated with C veins. They are characterised by major quartz, with minor K feldspar, biotite, apatite, rutile and anhydrite, and mostly have no selvage. They cut most M, EB and A veins, but are cut by C veins of the Early Stage, and by Transitional Stage veining.

• C veins (the A3 veins by Chang et al., 2017) - 0.1 to 8 mm thick, with straight walls, dominated by chalcopyrite ± pyrite with minor euhedral quartz. These, with B veins, with which they are commonly associated, are the dominant veins in the main ore zone. They are characterised by the predominance of sulphides, with minor quartz, K feldspar and biotite, and mostly have no selvage. They cut most M, EB, A and veins, but are cut by Transitional Stage veining.

B veins host the bulk of the molybdenite in the porphyry, whilst chalcopyrite occurs in both B and C veins. The mutual crosscutting relationships between EB, A and B veins suggest multistage magmatic-hydrothermal pulses. As detailed above, A veins (locally >30 vol.% of the rock) dominate in the barren core, whilst B veins (with a density of 5 to 10 vol.%) occur in the mineralised zone of the Monzogranite Porphyry, where they are much more abundant than the other quartz-dominated vein types. The intensity of potassic alteration in the barren core completely obliterates the porphyry texture of the Monzogranite Porphyry, where it is cut by a low density of quartz veins, but a high-density fracture-filling A veins. In contrast, B and C veins are mainly localised in zones of strong to weak potassic alteration peripheral to the barren core above ~4300 masl. The strong pervasive veining and mineralisation in the Early Stage suggest the potassic and propylitic alteration zoning pattern in the Monzogranite Porphyry and hornfels were produced during this stage, although the Transitional Stage veining is also accompanied by another pulse strong to moderate potassic alteration in the K feldspar Granite Porphyry (Chang et al., 2017).

► Transitional Stage, which postdates the K feldspar Granite Porphyry, but predates the intrusion of Quartz Albite Porphyry dykes. The principal vein types as described by Chang et al. (2017), are:

• UST (Unidirectional Solidification Textures) veins - the earliest veining recognised in the transition stage, composed predominantly of quartz swith minor K feldspar. They are found close to the contact with the Monzogranite Porphyry and are cut by transition stage A and B veins.

• EB (Early Biotite) veins (the EBT veins of Chang et al., 2017) - 0.2 to 2 mm thick, capillary biotite-quartz veins minor rutile. They are rarely seen in the K feldspar Granite Porphyry, but where present are cut by A veins.

• A veins (the A1T veins of Chang et al., 2017) - 5 to 30 mm thick, with irregular or straight walls, containing fine granular quartz with minor disseminations of K feldspar, biotite, apatite, rutile and anhydrite. They are largely barren and have no selvage, occurring within the K feldspar Granite Porphyry where they are cut by transition zone B veins.

• B veins (the BT veins of Chang et al., 2017) - 1 to 10 mm thick, with a typical banded texture and 'cockscomb' quartz and minor rutile, anhydrite and ankerite. Molybdenite is abundant with minor chalcopyrite and pyrite. The molybdenite typically occurs on vein margins, intergrown with anhedral, granular quartz ± K feldspar ± anhydrite, which are normally overgrown by the euhedral, free-standing 'cockscomb' quartz pointing into central voids of these veins with various chalcopyrite ± pyrite fillings. Although these veins are similar to the Early Stage B veins, they are differentiated by their apparent more abundant molybdenite. They veins have no, or only locally developed, sericite selvages and commonly occur in the deep Mo rich zone, cutting all of the veins described above. They are closely associated with the deep seated, Mo-rich zone below ~4300 masl. Mo grades in the K feldspar Granite Porphyry can be as high as 0.1 wt.% due to the density of B veins, although the Cu grade is generally <0.5 wt.%, contributed by the lower content in B and C veins.

• C veins (the A3T veins by Chang et al., 2017) - 0.1 to 3 mm thick, dominated by chalcopyrite ± pyrite with trace quartz. They occur in the K feldspar Granite Porphyry but are rare, and where present cut the transition zone A veins. These veins are identical to the Early Stage C veins, other than that they associated with the K feldspar Granite Porphyry.

► Late Stage, which postdates emplacement of Quartz Albite Porphyry dykes and is characterised by pyrite ± quartz veins with well-developed sericitic alteration halos, as well as zones of pervasive sericitic alteration overprinting the precursor potassic alteration. These are:

• D veins, which are straight walled, 1 to 10 mm thick and dominated by pyrite, with lesser euhedral quartz and sericite and commonly sericitic halos. Minor sulphides are chalcopyrite, galena and sphalerite and minor gangue is of calcite, rutile and fluorite. These veins occur throughout the deposit, and either cut or re-open and replace or augment the fill of all other vein types. Veins dominated by quartz are rarely found in Quartz Albite Porphyry dykes, which, in many cases, have been intensely altered to sericitic assemblages, with the intensity of the alteration decreasing toward the surrounding Monzogranite K feldspar Granite porphyries. These altered dykes, carry a considerable amount of pyrite with minor chalcopyrite, tennantite, enargite, sphalerite and galena, consistent with the low, <0.3 wt.% Cu and <0.01 wt.% Mo grades, but high S contents. An 8 m thick Quartz Albite Porphyry dyke intrudes the skarn ore, suggesting it is pre-Late Stage (Chang et al., 2017).

Transport and Precipitation of Sulphides - The Monzogranite Porphyry at Yulong is strongly oxidised, with sulphate the dominant sulphur species in fluid inclusions from magmatic quartz phenocrysts, while there is no observable sulphide. This indicates an ƒO2 above the sulphide-sulphur oxide buffer during magmatic processes. Both chalcophile metals and sulphur remain in solution and can be readily transported in an oxidised aqueous fluid where most of the sulphur occurs as sulphate. However, following magnetite crystallisation during early potassic alteration (e.g., M veins and replacive disseminated magnetite - deposit averages 0.4% magnetite), the sulphur species was reduced and became sulphide dominant with sulphate (anhydrite) and sulphide mineral assemblages occurring in fluid inclusions and in early mineralised veining (e.g., A veins), and predominantly sulphides during the main ore deposition (B and C veins). Replacement of amphibole and biotite by secondary magnetite, requires considerable amounts of Fe2+ to be oxidised to Fe3+, such that Fe2+ acts as a reducing agent to transform oxidised sulphur in the system to reduced sulphur. Hence, the crystallisation of magnetite initiates sulphate reduction, accompanied by decreasing pH and corresponding reduction of SO42- to H2S. Reduced S in H2S has a strong propensity to scavenge chalcophile elements and precipitate sulphides (after Ling et al., 2009).

Malasongduo Cu-Mo

Malasongduo is the second largest porphyry copper deposit in the Yulong porphyry copper belt, ~ 35 km SSE of the largest, Yulong (Hou et al., 2003). It is located on the flank of the Malasongduo anticline, just to the on the southwest of its axis, and comprises of a multistage porphyry complex that has intruded Early Triassic rhyolite lava and pyroclastic rocks. The deposit is largely concealed, only being exposed over an area of 0.1 km2.

The Malasongduo porphyry is a composite intrusion which has the form of a cylindrical stock-like body. According to Liang et al. (2009) it is mainly composed of an early stage quartz monzonite and K feldspar porphyry, and a late stage K feldspar porphyry. The two stage porphyries are different in composition. The early stage intrusions is relatively rich in Al2O3, MgO, CaO, Na2O, Fe2O3 Total, TiO2 and the second one is relatively rich in K2O and SiO2. The early stage porphyry has been dated at 36.9±0.4 Ma (U-Pb zircon; MSWD = 1.52) whilst the late stage porphyry has an age of 36.9±0.3 Ma (U-Pb zircon; MSWD = 1.38). The late stage porphyry that has undergone potassic alteration was dated at 36.9±0.6Ma (K-Ar mica; MSWD = 1.36). The comparable ages of both porphyries suggest they were emplaced at essentially the same time. Isotopic data suggest the mineralised system cooled from ~800°C (zircon crystallisation temperature), through 500°C (Re-Os closure temperature of molybdenite) to <300°C (Ar closure temperature of biotite) in a very short time, most likely <1 m.y. (Liang et al., 2009).

According to Hou et al. (2003), the dominant mineralised phase is a monzogranite porphyry, presumably the early stage intrusion of Liang et al. (2009). The alteration assemblages are similar to those described above at the Yulong deposit. These include K silicate, silicification and phyllic (quartz-sericite) alteration. Peripheral rhyolitic rocks surrounding the porphyry intrusion have proximal K silicate alteration, grading to a distal propylitic halo and a phyllic zone overprinting the transition between the two. The K silicate zone adjacent to the intrusion hosts significant Cu-Mo mineralisation.

The porphyry intrusions and surrounding rhyolitic country rocks host veinlet and disseminated pyrite-chalcopyrite ±molybdenite mineralisation that forms a steeply dipping, cylindrical deposit, that is 950 m x 800 m wide, and persists over a vertical interval of ~690 m. Mineralisation is both laterally and vertically zoned. In plan view, a Cu core grades outward through Cu-Mo to an outer Ag-Pb-Zn zone. Vertically, the orebody ranges from veinlet and disseminated Cu at depth, to a fine veinlet Cu mineralisation at shallower levels, overlain by a supergene enrichment zone (Tang and Luo, 1995). Veinlet and disseminated Cu and Cu-Mo mineralisation is largely hosted in the monzogranite porphyry and adjacent rhyolitic country rocks, whilst minor Pb-Zn sulphides are restricted to the latter (Hou et al., 2003).

Four generations of veining are recognized in the main orebody: i). quartz sulphide veins, including quartz-pyrite-chalcopyrite, quartz-pyrite-bornite and quartz-chalcocite; ii). biotite-chalcopyrite veins; iii). calcite-quartz-pyrite-chaclopyrite veins; and iv). tourmaline-quartz-chalcopyrite-pyrite-molybdenite veins (Hou et al., 2003).

Duoxiasongduo Cu

This deposit is ~20 km ESE of Yulong and is also developed in the core of the Malasongduo anticline where it intruded a late Triassic mudstone-sandstone sequence. Mineralisation is hosted by a multistage porphyry intrusive exposed over an area of 0.3 km2 ranging from an early monzogranite porphyry to a late stage granite porphyry, with ages of 52 (Rb-Sr) and 41 (U-Pb) Ma respectively. The porphyries intrude and metamorphose Late Triassic sandstone and mudstone to hornfels along the intrusive margins. Both the porphyry and the hornfels have been subjected to porphyry-style hydrothermal alteration with a zonation similar to the Yulong and Malasongduo deposits (Ma, 1990; Tang and Luo, 1995).

Mineralisation occurs a 600 x 500 m zone with a 570 m vertical extent, and is located in the southern half of the porphyry stock and in the surrounding hornfels and altered sediments. The deposit is pipe shaped with a vertical zonation from Cu-Mo rich at depth to Cu rich at shallower levels. No supergene blanket is evident, probably having been removed by erosion. Quartz-sulphide and sulphide veinlets are generally <2 mm thick, containing quartz-pyrite-chalcopyrite and minor molybdenite, bornite and chalcocite, while the sulphide veins are composed of pyrite, chalcopyrite and minor bornite and chalcocite, while sulphide veins comprise pyrite and chalcopyrite with minor bornite and chalcocite (Hou et al., 2003).

Narigongma Cu-Mo

This deposit represents a continuation of the Yulong Belt to the NW along the North Qiangtang Terrane, in the northern extremity of the greater Jinshajiang-Ailaoshan-Red River Metallogenic Belt. It is interpreted to constitute a post-collisional porphyry Cu deposit, and is located in southern

Qinghai Province (Tibet), ~400 km northwest of the main cluster of the Yulong porphyry Cu-Mo-Au belt. It has a similar age of 43 to 40 Ma as the latter cluster, but a different mineral assemblage. Mineralisation is associated with Eocene granodiorite and granite intrusions that were emplaced into a

Middle to Late Permian volcanic-sedimentary sequence. The Permain sequence consists of basalt, basaltic andesite and minor andesite, interbedded with

sandstone, slate and muddy limestone, and strikes NW at ~240°, and -dips 30 to 40°SW.

The ~43.3 Ma P1 Porphyry, principally occurring as a 1.8 x 0.4 to 1.0 km biotite granite stock is the earliest Eocene intrusion, intruded by a number of smaller, ~43.6 Ma fine-grained granite porphyry stocks, known as the P2 Porphyry, and several post-mineral ~41.7 Ma quartz diorite porphyry dykes. The P1 Porphyry locally grades to granodioritic compositions at its margins. The main Cu-Mo mineralisation at Narigongma is associated with the P1 porphyry. It's phenocrysts constitute 20 to 35 vol.% of the rock, and include variable amounts of plagioclase, K eldspar, quartz, biotite and minor hornblende. The matrix is quartzo-feldspathic and consists of fine-grained quartz, feldspar and biotite, with accessory minerals that include apatite, rutile, zircon and titanite. The P2 Porphyry has a fine-grained texture and is grey to white, and is generally exposed as NE-striking dykes that intrude the Permian volcanic-sedimentary sequence and P1 Porphyry. Phenocrysts in the P2 porphyry are mainly K feldspar, biotite, quartz and minor plagioclase, and are relatively small,<4 mm, set in a quartzo-feldspathic matrix, with accessory zircon, titanite and apatite. The P2 Porphyry has experienced weak to moderate quartz-sericite phyllic alteration.

The hydrothermal alteration pattern embracing the deposits is generally characterised by concentric zones that range from an inner potassic core, grading outward to phyllic and argillic alteration zones, and an outer propylitic halo. Hypogene mineralisation at Narigongma was characterised by early-stage precipitation of molybdenite during potassic alteration and late-stage emplacement of chalcopyrite during phyllic alteration.

The potassic alteration assemblages in the P1 Porphyry and surrounding volcanic-sedimentary wallrocks is characterised by K feldspar, biotite and abundant quartz, subdivided into early-stage K feldspar and late-stage biotite phase. The K feldspar alteration, pre-dates the quartz diorite porphyries, and occurs as veins, veinlets and selective pervasive mineral replacement. Vein- or veinlet-forming K feldspar is the dominant style of potassic alteration, occurring as quartz-K feldspar and quartz-molybdenite ±K-feldspar, present as micro-veinlets in stockwork fracture arrays. Quartz-K feldspar veins are irregular to planar and discontinuous to continuous, with widths ranging from <1 to 5 mm, and are characterised by the absence of sulphides. These veins cut quartz and feldspar phenocrysts in the P1 Porphyry, and are truncated by quartz-molybdenite ±K feldspar and biotite veins. Quartz in the latter veins is typically granular and generally lacks internal symmetry, characteristic of quartz in A-type veins in porphyry Cu deposits (e.g., Gustafson and Hunt, 1975). K feldspar in the veins is generally replaced by clay minerals and is white. Quartz-molybdenite ±K feldspar veins are irregular to planar with variable 0.5 to 12 mm widths and are characterised by disseminations or clots of molybdenite and K feldspar.

The quartz-molybdenite ±K feldspar veins are cut by quartz-pyrite-chalcopyrite and pyrite ±quartz ±chalcopyrite veins that are associated with phyllic alteration. Quartz in the quartz-molybdenite ±K feldspar veins is also granular in shape and lacks internal symmetry. Outward into the biotite zone, which is typical of the wallrocks closely surrounding the P1 Porphyry intrusion, alteration is characterised by abundant biotite, quartz, magnetite and minor K feldspar, and is found in two main modes: i). selveges bordering quartz-molybdenite ±K feldspar and quartz-chalcopyrite veins; and ii). selective replacement of primary minerals such as biotite, hornblende and feldspar. Locally, biotite alteration

also occurs as veinlet filling. Quartz-molybdenite ±K feldspar mineral assemblages characterize the major vein type associated with biotite

alteration at Narigongma. Quartz-chalcopyrite and chalcopyrite veinlets are present, but poorly developed in the biotite zone of the Narigongma deposit.

Due to the high mafic composition of the wall rocks at Narigongma, propylitic alteration is strongly developed, where it has a mineral assemblage of chlorite-epidote-calcite. Mafic minerals are replaced by chlorite ±magnetite, and plagioclase is altered to epidote-calcite ±sericite. The rocks close to the P1 Porphyry have a high sulfide content, mainly pyrite. Propylitic alteration is irregularly developed and typically pervasive, apart from some small epidote veinlets. The propylitic alteration zone surrounds the phyllic alteration and is mainly found in the Permian wallrocks. Epidote ±quartz ±chlorite ±calcite veins are cut by pyrite veins associated with phyllic alteration, suggesting that the propylitic alteration pre-dated the latter, and was probably contemporaneous with potassic alteration.

Phyllic alteration occurs as i). pervasive developments, or as ii). sleveges sandwiching pyrite-bearing veins, and has overprinted unaltered rocks and earlier alteration assemblages. It us typified by assemblages dominated by sericite, quartz, pyrite and calcite, although chlorite and rutile are extensively developed in the assemblage in the volcanic-sedimentary sequence. Phyllic alteration has affected all the porphyry types, including the youngest quartz diorite porphyries.

The principal vein assemblages associated with phyllic alteration are typically pyrite-bearing, and include:

i). quartz-pyrite-chalcopyrite, which are planar, with widths of 2 to 4 mm, with diffuse margins grading into well-developed phyllic selveges. In addition to granular quartz, subhedral prismatic quartz grains locally occur with their long axes perpendicular to vein walls, indicating that the veins formed by open cavity filling. Pyrite and chalcopyrite in the veins generally occur along the boundaries of quartz grains.

ii). pyrite-chalcopyrite ±quartz, which, in contrast, pyrite-chalcopyrite ±quartz veins are irregular and continuous to discontinuous, with widths varying from 0.2 to 4.0 mm, characterised by low quartz contents or no quartz at all. Pyrite within the veins is anhedral and usually fractured, with or without other minerals filling the fractures. Chalcopyrite within the veins is irregular, and generally occurs separately from the pyrite. Locally, chalcopyrite is found as enclaves in pyrite, or as veinlets cutting pyrite, suggesting multistage chalcopyrite deposition.

iii). pyrite ±chalcopyrite ±quartz veins are similar to the pyrite-chalcopyrite ±quartz veins, and are characterised by the absence of, or only weak developments chalcopyrite. Pyrite in the veins is anhedral and typically fractured with or without other minerals filling the fractures.

iv). pyrite ±quartz veins are planar to irregular, and characterised by an absence of chalcopyrite. Pyrite in the veins is anhedral to subhedral.

No cross-cutting relationships have been observed between the quartz-pyrite-chalcopyrite, pyrite-chalcopyrite ±quartz, and pyrite ±chalcopyrite ±quartz veins, indicating they were coeval, whilst the pyrite ±quartz veins cut pyrite ±chalcopyrite ±quartz veins and are therefore younger. In contrast, quartz-molybdenite veins are rarely associated with phyllic alteration.

Argillic or intermediate argillic alteration has affected all the rock units at Narigongma, but is mainly found in the central part of the P1 Porphyry intrusion, where it overprints unaltered rocks and earlier alteration assemblages. Argillic alteration is typically controlled by fractures or faults and occurs as a N- to NE-trending belt striking at 0 to 20° with a width of several to tens of metres over a length of tens to hundreds of metres. The clay minerals are mainly kaolinite with minor montmorillonite.

The information in this Narigongma description is largely drawn from Yang et al. (2014) as cited below.

MINERAL RESOURCES

Resource figures from the significant deposits of the belt are as follows (Hou, et al., 2003):

Yulong - 630 Mt @ 0.99% Cu, 0.028% Mo, 0.35 g/t Au, for 6.22 Mt of Cu (including ~60 Mt @ 4.74% Cu, 4.5 g/t Au).

(or 850 Mt @ 0.84% Cu, 0.02% Mo, Fan, 1984)

Malasongduo - 230 Mt @ 0.44% Cu, 0.14% Mo, 0.06 g/t Au, for 1.0 Mt of Cu.

338 Mt @ 0.45% Cu, 0.014% Mo, 0.06 g/t Au (USGS, Mineral Resource Database, viewed Jan. 2019)

Duoxiasongduo - 130 Mt @ 0.38% Cu, 0.04% Mo, 0.05 g/t Au, for 0.5 Mt of Cu;

248 Mt @ 0.38% Cu, 0.04% Mo, 0.06 g/t Au (USGS, Mineral Resource Database, viewed Jan. 2019)

Mangzong - 70 Mt @ 0.34% Cu, 0.03% Mo, 0.02 g/t Au, for 0.25 Mt of Cu.

Zhanaga - 80 Mt @ 0.36% Cu, 0.03% Mo, 0.03 g/t Au, for 0.3 Mt of Cu.

Narigongma is reported to have a resource of ~0.46 Mt of contained Cu with an average grade of ~0.32 wt.% Cu and

~0.25 Mt of contained Mo at an average grade of ~0.06 wt.% Mo (Yang et al., 2014). This would equate to a tonnage of 140 Mt of 'ore', based on the Cu data, and 410 Mt of 'ore' based on the Mo data.

For detail consult the reference(s) listed below.

The most recent source geological information used to prepare this decription was dated: 2014.

Record last updated: 3/2/2024

This description is a summary from published sources, the chief of which are listed below.

© Copyright Porter GeoConsultancy Pty Ltd. Unauthorised copying, reproduction, storage or dissemination prohibited.

Yulong

|

|

|

|

|

Chang, J., Li, J.-W. and Audetat, A., 2018 - Formation and evolution of multistage magmatic-hydrothermal fluids at the Yulong porphyry Cu-Mo deposit, eastern Tibet: Insights from LA-ICP-MS analysis of fluid inclusions: in Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta v.232, pp. 181-205.

|

Chang, J., Li, J.-W. and Zhou, L., 2020 - Molybdenum isotopic fractionation in the Tibetan Yulong Cu-Mo deposit and its implications for mechanisms of molybdenite precipitation in porphyry ore systems: in Ore Geology Reviews v.123, doi.org/10.1016/j.oregeorev.2020.103571.

|

Chang, J., Li, J.-W., Selby, D., Liu, J.-C. and Deng, X.-D., 2017 - Geological and Chronological Constraints on the Long-Lived Eocene Yulong Porphyry Cu-Mo Deposit, Eastern Tibet: Implications for the Lifespan of Giant Porphyry Cu Deposits : in Econ. Geol. v.112, pp. 1719-1746.

|

Deng, J., Wang, Q., Li, G., Li, C. and Wang, C., 2014 - Tethys tectonic evolution and its bearing on the distribution of important mineral deposits in the Sanjiang region, SWChina: in Gondwana Research v.26, pp. 419-437.

|

Fan, P.-F., 1984 - Geologic setting of selected Copper deposits of China: in Econ. Geol. v.79, pp. 1785-1795.

|

Gardiner, N.J., Searle, M.P., Robb, L.J. and Morley, C.K., 2015 - Neo-Tethyan magmatism and metallogeny in Myanmar - An Andean analogue?: in J. of Asian Earth Sciences v.106, pp. 197-215.

|

Hao, H., Park, J.-W., Zheng, Y.-C. and Hwang, J., 2024 - Role of chalcophile element fertility in the formation of the eastern Tethyan post-collisional porphyry Cu deposits: in Mineralium Deposita v.59, pp. 1579-1594.

|

Hou, Z. and Cook, N., 2009 - Metallogenesis of the Tibetan collisional orogen: A review and introduction to the special issue: in Ore Geology Reviews v.36, pp. 2-24.

|

Hou, Z., Xie, Y., Xu, W., Li, Y., Zaw, K., Beaudoin, G., Rui, Z., Huang, W. and Luobu, C., 2007 - Yulong Deposit, Eastern Tibet: A High-Sulfidation Cu-Au Porphyry Copper Deposit in the Eastern Indo-Asian Collision Zone: in International Geology Review v.49, pp. 235-258.

|

Hou, Z., Zeng, P., Gao, Y, Du, A. and Fu, D., 2006 - Himalayan Cu-Mo-Au mineralization in the eastern Indo-Asian collision zone: constraints from Re-Os dating of molybdenite: in Mineralium Deposita v.41, pp. 33-45.

|

Hou, Z., Zhang, H., Pan, X. and Yang, Z., 2011 - Porphyry Cu (-Mo-Au) deposits related to melting of thickened mafic lower crust: Examples from the eastern Tethyan metallogenic domain: in Ore Geology Reviews v.39, pp. 21-45.

|

Hou, Z.,Khin Zaw, Pan, G., Mo, X., Xu, Q., Hu, Y. and Li, X., 2007 - Sanjiang Tethyan metallogenesis in S.W. China: Tectonic setting, metallogenic epochs and deposit types: in Ore Geology Reviews v.31, pp. 48-87. doi.org/10.1016/j.oregeorev.2004.12.007.

|

Hou, Z.Q., Ma, H., Khin, Z., Zhang, Y., Wang, M., Wang, Z., Pan, G. and Tang, R., 2003 - The Himalayan Yulong Porphyry Copper belt: product of large-scale strike-slip faulting in eastern Tibet: in Econ. Geol. v98 pp 125-145

|

Hou, Z.Q., Zhong, D., Deng, W.M. and Zaw, K., 2005 - A Tectonic Model for Porphyry Copper-Molybdenum-Gold Deposits in the Eastern Indo-Asian Collision Zone: in Porter, T.M. (Ed), 2005 Super Porphyry Copper & Gold Deposits - A Global Perspective, PGC Publishing, Adelaide, v.2 pp. 423-440

|

Huang, M.-L., Bi, X.-W., Hu, R.-Z., Chiaradia, M., Zhu, J.-J., Xu, L.-L. and Yang, Z.-Y., 2024 - Linking Porphyry Cu Formation to Tectonic Change in Postsubduction Settings: A Case Study from the Giant Yulong Belt, Eastern Tibet: in Econ. Geol. v.119, pp. 279-304. doi: 10.5382/econgeo.5052.

|

Huang, M.-L., Bi, X.-W., Hu, R.-Z., Gao, J.-F., Xu, L.-L., Zhu, J. and Shang, L.-B., 2019 - Geochemistry, in-situ Sr-Nd-Hf-O isotopes, and mineralogical constraints on origin and magmatic-hydrothermal evolution of the Yulong porphyry Cu-Mo deposit, Eastern Tibet: in Gondwana Research v.76, pp 98-114.

|

Huang, M.-L., Bi, X.-W., Richards, J.P., Hu, R.-Z., Xu, L.-L., Gao, J.-F., Zhu, J.J. and Zhang, X.-C., 2019 - High water contents of magmas and extensive fluid exsolution during the formation of the Yulong porphyry Cu-Mo deposit, eastern Tibet: in J. of Asian Earth Sciences v.176, pp. 168-183.

|

Jiang, Y.-H., Jiang, S.-Y., Ling, H.-F. and Dai, B.-Z., 2006 - Low-degree melting of a metasomatized lithospheric mantle for the origin of Cenozoic Yulong monzogranite-porphyry, east Tibet: Geochemical and Sr-Nd-Pb-Hf isotopic constraints: in Earth and Planetary Science Letters v.241, pp. 617-633.

|

Jiang, Y.H., Yong, S.Y., Dai, B.Z. and Ling, H.F., 2008 - Discrimination of Ore-Bearing and Barren Porphyries in the Yulong Porphyry Copper Ore Belt, Eastern Tibet: in International Geology Review v.50, pp. 583-595.

|

Li, J, Qin, K., Li, G., Cao, M., Xiao, B., Chen, L., Zhao, J., Evans, N. and McInnes, B.I.A., 2012 - Petrogenesis and thermal history of the Yulong porphyry copper deposit, Eastern Tibet: insights fromU-Pb and U-Th/He dating, and zircon Hf isotope and trace element analysis: in Mineralogy & Petrology v.105, pp. 201-221.

|

Liang, H.-Y., Campbell, I.H., Allen, C., Sun, W.-D., Liu, C.-Q., Yu, H.-X., Xie, Y.-W. and Zhang, Y.-Q., 2006 - Zircon Ce4+/Ce3+ ratios and ages for Yulong ore-bearing porphyries in eastern Tibet: in Mineralium Deposita v41 pp 152-159

|

Liang, H.-Y., Mo, J., Sun, W.-D., Zhang, Y.-Q., Zeng, T., Hu, G.-Q. and Allen, C.M., 2009 - Study on geochemical composition and isotope ages of the Malasongduo porphyry associated with Cu-Mo mineralization: in Chinese, English Abstract, Acta Petrologica Sinica v.25, pp. 385-392.

|

Liang, H.Y., Sun, W., Su W.C. and Zartman, R.E., 2009 - Porphyry Copper-Gold Mineralization at Yulong, China, Promoted by Decreasing Redox Potential During Magnetite Alteration: in Econ. Geol. v.104, pp. 587-596.

|

Mao, J., Pirajno, F., Lehmann, B., Luo, M. and Berzina, A., 2014 - Distribution of porphyry deposits in the Eurasian continent and their corresponding tectonic settings: in J. of Asian Earth Sciences v.79, pp. 576-584.

|

Sun, M., Monecke, T., Reynolds, T. J. and Yang, Z., 2021 - Understanding the evolution of magmatic-hydrothermal systems based on microtextural relationships, fluid inclusion petrography, and quartz solubility constraints: insights into the formation of the Yulong Cu-Mo porphyry deposit, eastern Tibetan Plate: in Mineralium Deposita v.56, pp. 823-842.

|

Wang, C., Bagas, L., Lu, Y., Santosh, M., Dua, B. and McCuaig, C., 2016 - Terrane boundary and spatio-temporal distribution of ore deposits in the Sanjiang Tethyan Orogen: Insights from zircon Hf-isotopic mapping: in Earth Science Reviews v.156, pp. 39-65.

|

Yang, L.Q., He, W.Y., Gao, X., Xie, S.X. and Yang, Z., 2018 - Mesozoic multiple magmatism and porphyry-skarn Cu-polymetallic systems of the Yidun Terrane, Eastern Tethys: Implications for subduction- and transtension-related metallogeny: in Gondwana Research v.62, pp. 144-162

|

Yang, Y.-F. and Wang, P., 2017 - Geology, geochemistry and tectonic settings of molybdenum deposits in Southwest China: A review: in Ore Geology Reviews v.81, pp. 965-995.

|

Yang, Z., Hou, Z., Xu, J., Bian, X., Wang, G., Yang, Z., Tian, S., Liu, Y. and Wang, Z., 2014 - Geology and origin of the post-collisional Narigongma porphyry Cu-Mo deposit, southern Qinghai, Tibet: in Gondwana Research v.26, pp. 536-556. dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2013.07.012

|

Zhang, K.-J., Zhang, Y.-X., Tang, X.-C. and Xia B., 2012 - Late Mesozoic tectonic evolution and growth of the Tibetan plateau prior to the Indo-Asian collision: in Earth Science Reviews v.114, pp. 236-249.

|

|

Porter GeoConsultancy Pty Ltd (PorterGeo) provides access to this database at no charge. It is largely based on scientific papers and reports in the public domain, and was current when the sources consulted were published. While PorterGeo endeavour to ensure the information was accurate at the time of compilation and subsequent updating, PorterGeo, its employees and servants: i). do not warrant, or make any representation regarding the use, or results of the use of the information contained herein as to its correctness, accuracy, currency, or otherwise; and ii). expressly disclaim all liability or responsibility to any person using the information or conclusions contained herein.

|

Top | Search Again | PGC Home | Terms & Conditions

|

|